A New Jersey real estate developer helped restore a historic Negro leagues baseball stadium.

After graduating high school in Paterson, New Jersey, Baye Adofo-Wilson L’97 didn’t see many local opportunities for himself, so he decided to join the US Army. During basic training, he met four other Paterson natives. When asked by their drill sergeants why they had chosen the military, they too cited the lack of job opportunities in Paterson.

Thirty years later, with three degrees and a resume that includes stints as a Harvard University Loeb Fellow and deputy mayor/director of economic and housing development for the City of Newark, Adofo-Wilson is trying to change his hometown’s fortunes.

As the head of the real estate development firm BAW Development, Adofo-Wilson recently helped spearhead a $108 million project in Paterson that included the restoration of a historic Negro leagues baseball stadium, 75 units of affordable housing for people 55 and older, a parking garage, and a museum dedicated to the Negro leagues.

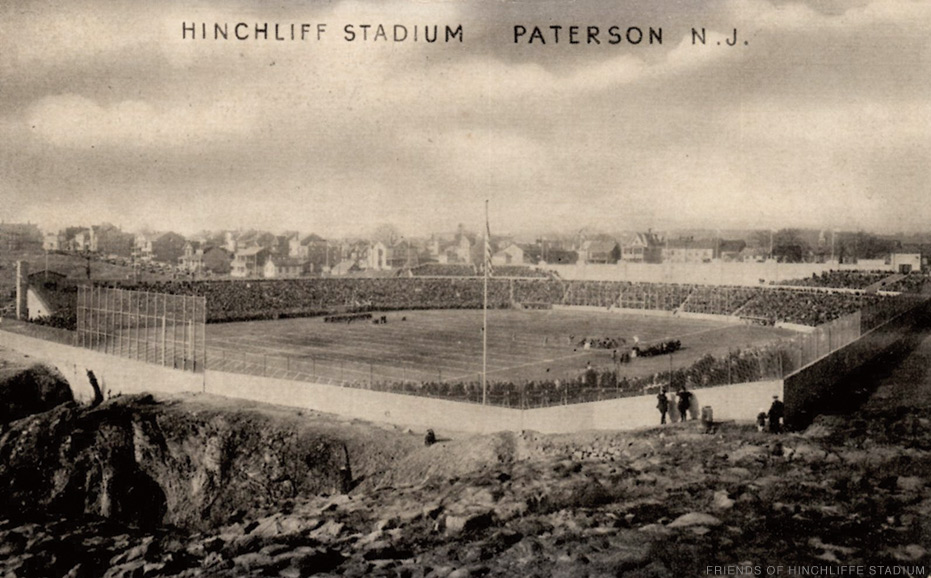

Hinchliffe Stadium, a 1932 structure that had been abandoned and neglected since 1997, was reopened on May 19. Actor Whoopi Goldberg, US Senator Cory Booker, and several baseball luminaries attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony. Two days later, Hinchliffe Stadium held its first sporting event in 26 years, a professional baseball game between the New Jersey Jackals and the Sussex County Miners of the independent Frontier League. The host Jackals won, 10–6.

After working on the project for four years, it was “an accomplishment for me personally and professionally to be in the community where I grew up and help put this facility back into use,” says Adofo-Wilson, whose company develops mixed-use projects in urban communities. “This has been a real milestone in my career. I think the biggest thing I felt was a sense of relief and accomplishment.”

Hinchliffe Stadium—which played host to Negro leagues legends like Josh Gipson and “Cool Papa” Bell before Jackie Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier in 1947—was on the verge of being demolished. It is one of five remaining stadiums in the country where Negro leagues games were played. It is now owned by the Paterson Board of Education, and the developers have a 75-year lease from the Paterson Public School District. They will host sporting events year-round, including baseball, football, soccer, and track and field, as well as concerts and festivals.

For Adofo-Wilson, whose parents attended segregated schools in North Carolina and South Carolina, the stadium’s rich history is especially meaningful. “It means a lot to me, the accomplishments of Black players in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s” against the backdrop of Jim Crow laws, he says.

After earning his bachelor’s degree from Rutgers University–Newark and a master’s in city and regional planning from Cornell, Adofo-Wilson wanted to study law because “I needed to understand how the United States worked,” he says. “I would be harassed by the police while driving to work, walking down the street, or hanging in the park. And when I tried to challenge the harassment, I didn’t have language to state my frustrations.”

He also hoped law school would help him translate his urban planning know-how into brick-and-mortar reality. “In Black communities, all the time, plans are developed but never implemented. I wanted to make sure that I had skills that would help me implement those plans, and law school felt like the best vehicle at that time.”

He chose to attend Penn because it was “an urban campus … woven into West Philadelphia,” he says. “It was exciting to see a college have an impact locally. I’ve tried to encourage universities to be active participants in the communities that they exist in.” (He cites work with Rutgers University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology, and Essex County College on various projects; Montclair State University was part of the Hinchliffe Stadium site redevelopment.)

As a law student, Adofo-Wilson could take elective courses outside the school. He chose two Wharton real estate classes that “exposed me to ways that I could use law as a real estate developer,” he says. “Law schools are about representation of clients, but Wharton really provided me with a glimpse at how I could become a real estate developer.”

One of his most impactful faculty members was Regina Austin L’73 [“Legal Zoom-In,” Nov|Dec 2016], an emeritus professor at Penn Carey Law whom Adofo-Wilson characterizes as “the most committed professor to her students and to the larger Black community that I was ever in proximity to. She was very creative in her problem-solving techniques, challenging overall theories from multiple angles, making sure that we were resourceful in our strategies for representing Black communities.”

Austin—who came to Penn as an assistant professor in 1977 and retired in 2021 after a groundbreaking career focusing on the impact of law on cultural conflicts arising from race, gender, and class inequality—recalls Adofo-Wilson as a “wonderful and unforgettable” student. “He came to my class possessing the wisdom of an old soul who knew the importance and liberating potential of marshaling Black people’s cultural, social, political, and economic capital or resources to achieve the greater good,” she says.

Adofo-Wilson is currently working on two development projects in Northern New Jersey and South Jersey. He’ll know the Hinchliffe Stadium project has been a success when “more young people in Paterson call it their home field,” he says. —Jon Caroulis