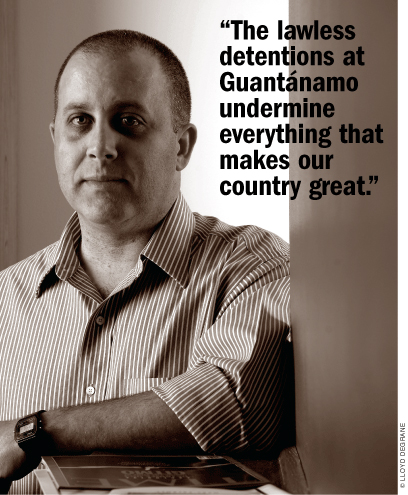

Why is attorney Marc Falkoff representing detainees at Guantánamo Bay and publishing a book of their poetry?

By Samuel Hughes | Illustration by Phillip Fivel Nessen

O Sea, do our chains offend you?

It is only under compulsion that we daily come and go.

Do you know our sins?

Do you understand we were cast into this gloom?

O Sea, you taunt us in our captivity.

You have colluded with our enemies and you cruelly guard us …

You have been beside us for three years, and what have you gained?

Boats of poetry on the sea; a buried flame in a burning heart.

—From “Ode to the Sea,” by Ibrahim Al Rubaish.

That the above lines now appear in a book—Poems From Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak (University of Iowa Press)—is a testimony to human perseverance. Not just because some of the poems written by detainees at the United States military facility at Guantánamo Bay were first scrawled in toothpaste on Styrofoam cups or etched into the cups with small stones, since in their first year of captivity the prisoners were not allowed to use pen and paper. What’s remarkable is that somebody on the outside, with seemingly nothing to gain, found a way to hear those voices in the face of Kafkaesque obstacles, and then made sure that they could be heard by the world.

Marc Falkoff C’88, who collected and edited Poems From Guantánamo, has a Ph.D. in American literature from Brandeis, having majored in English and psychology at Penn. But his literary background was less important to the making of the book than his legal training—and his conscience. Now an assistant professor of law at Northern Illinois University, Falkoff began representing the prisoners while an associate at the New York office of Covington & Burling.

Before he and other justice-driven lawyers got involved, “Guantánamo was truly a ‘black hole’ from which no information—and certainly not the voices of the detainees—could escape,” writes Falkoff in the book’s acknowledgements. All of the detainees were decreed “enemy combatants” by the U.S. government, and were described as “among the most dangerous, best-trained, vicious killers on the face of the Earth” by former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Though several hundred have since been released, the rest (about 340) have spent the past six years—more than 2,000 days and nights—in the maximum-security detention center at Guantánamo Bay. Only a few—and none of Falkoff’s clients—have been given a trial or charged with a specific crime.

In his unpublished journal, Falkoff recalls a 2004 conversation with one of the Yemeni prisoners he represents, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif:

I tell Adnan that the government claimed the right to hold him in Guantánamo, without charge or trial, for the duration of the “war on terrorism.” Because this “war” is against an inchoate idea, it could go on indefinitely. For Adnan that means he could be held in this prison forever.

In the middle of our email interview, I asked Falkoff a blunt question. I might as well get it out of the way now, since those suspicious of his efforts aren’t likely to give him or the men he represents a fair hearing until it’s been addressed: “What do you say to those who argue that some of the prisoners—the hardcore cases, assuming there really are some—might want to kill you simply for being an American?”

Of course, he’s already been asked much blunter variations of that question. (“Are you the attorney that is defending one of those terrorist scumbags at GITMO? I need to ask you this: HOW do you sleep at night defending a scumbag like that [sic] wants both you and I to die a painful death? Have you been ostracized by your peers? Do you feel like a traitor? Just curious …”)

Falkoff’s response comes crackling back through the ether.

“My clients are not members of Al Qaeda! They don’t want to kill me or you or any other American! If there are Al Qaeda operatives in Guantánamo, then I want them to be put on trial, convicted, sentenced, and thrown into prison, of course. But we can’t just let Pakistani police officers pick up a random group of Arabs at the border, hand them over to U.S. troops, and then have the detainees tossed into prison for the rest of their lives without ever being charged with anything.”

That, in a nutshell, is what drives him.

On June 28, 2004, after more than two years of legal wrangling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Guantánamo detainees had the right to file habeas corpus petitions in federal court—in other words, to challenge the legality of their detention. Falkoff, who once served a stint as the habeas corpus Special Master in a federal court in Brooklyn, immediately called the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and asked if it needed volunteer attorneys to help out with the habeas hearings that would inevitably follow. The answer was an emphatic Yes. Falkoff agreed to take on 13 of the Yemenis, a number that grew to 17. He was, and is, working on a pro bono basis, and any profits from the book will go to the CCR.

Falkoff is not alone, of course. More than 250 lawyers and law professors from around the country, calling themselves the Guantánamo Bay Bar Association, have volunteered their time and energies to righting what they see as a grave injustice. The work has been grueling, time-consuming, and frustrating. In order to spend a total of less than 20 hours with his clients, Falkoff had to take five full days away from work. Since all of his clients speak Arabic, he had to bring along (and pay) an interpreter. He had to leave all his notes of his conversations with his clients behind, and could review them only at a secure federal facility in suburban Washington.

That’s nothing compared to the difficulties he first encountered, which included the fact that he didn’t even know who his clients were, since the military had kept their identities secret for three years. In his journal, he wrote:

We had learned the names of our Yemeni clients, I explain, only when their families showed up at a human-rights conference in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, seeking help. I explain to Adnan that initially the Pentagon refused to allow lawyers to visit Guantánamo, insisting that our meetings with our clients be monitored and videotaped. I tell Adnan that we convinced a judge that such monitoring would be a gross violation of the attorney-client privilege, and that eventually we were given the green light to meet with our clients, unmonitored.

We both look up at the video camera in the corner of the interview cell. “They assure me it’s off,” I say, and we both chuckle.

Falkoff describes himself as a “left-of-center kind of lawyer,” but having worked in the courts and associated with a goodly number of prosecutors, he says that his “natural inclination is not to disbelieve government agents when they tell me something.

“Here, we had the military telling us that the detainees at Gitmo were highly trained Al Qaeda operatives,” he adds. “Was it safe to leave my pen on the table? Were my clients evil geniuses? Were they all Muslim variations on Hannibal Lecter?”

Far from it, he concluded: “My clients are overwhelmingly young, polite, self-effacing men. It only takes sitting down with these men for a few hours to get a sense of who they really are.” Some were in Afghanistan as aid workers, he says; some as teachers. Others were doing missionary or charitable work. A couple had gone there long before 9/11 to work with the Taliban with the idea of building a model Islamic society.

“You can consider those men naïve or disagree with their choices, but they certainly did not go to Afghanistan with any thoughts of harming the U.S.,” he says. “I’m not saying that there are no Al Qaeda operatives at Guantánamo, but I will tell you that the great majority of the men at Gitmo are innocent of all wrongdoing.”

Here is Adnan’s story, as he related it to Falkoff and (many times) to his interrogators:

After sustaining a serious head injury in a 1994 automobile accident, he had spent years trying to find affordable medical treatment. Somebody told him about the health-care office of a Pakistani aid worker in Afghanistan who would treat him, and there he went, sometime in 2001. He was still there on September 11 of that year, and when the Americans began bombing the Taliban the following month, Adnan fled, arriving at the border town of Khost and making his way into Pakistan.

There Pakistani forces arrested him, along with about 30 other men who looked Arabic, most of them Yemenis. Adnan later learned that each of them had been turned over to the U.S. military for a bounty of $5,000.

A British historian named Andy Worthington later told Falkoff how the Pakistanis likely came to pick up those 30 men. It seems that there were two routes out of Tora Bora, where hundreds of Al Qaeda fighters had been holed up. One was to Khost; the other was across the White Mountains. The Al Qaeda operatives took the latter route. The Americans, “oblivious to the actual escape route of the fighters,” had focused on the Khost road, reports Falkoff. “When the Pakistanis seized the 30 Arab civilians passing through Khost, therefore, the Americans touted the capture as a successful roundup of Al Qaeda soldiers.” Unfortunately, those soldiers had already escaped through the mountains.

It was an understandable mistake, but one with profound consequences. The Pakistanis treated the Yemenis harshly, according to Falkoff, then turned them over to the Americans. At that point, the Yemenis thought they would be treated fairly.

Here is the summary of evidence against Adnan by the Combatant Status Review Tribunal:

a) The detainee is an al Qaida fighter:

In the year 2000 the detainee reportedly traveled from Yemen to Afghanistan.

The detainee reportedly received training at the al-Farouq training camp.

b) The detainee engaged in hostilities:

1) In April 2001 the detainee reportedly returned to Afghanistan.

2) The detainee reportedly went to the front lines in Kabul.

“I tell [Adnan] that when I first saw the accusations, I thought they looked serious,” Falkoff writes. “But that when I looked at the government’s evidence, I was amazed. There was nothing there. Nothing at all trustworthy. Nothing that could be admitted into evidence in a court of law. Nothing that was remotely persuasive, even leaving legal niceties aside.”

At most, he adds, “there was incredibly unreliable hearsay, often taken from other detainees who were—in the words of a military representative—‘known liars,’ or else whom we now know to have been tortured.”

According to a study by Seton Hall Law School that Falkoff cites, only 8 percent of the detainees at Guantánamo are even accused of being Al Qaeda fighters. Only 5 percent of the detainees were picked up on the battlefield by U.S. troops.

Though he could only speak about unclassified information, Falkoff notes that “it is now public knowledge that ‘Detainee 063’—who is Mohammed al-Qahtani—is personally responsible for ‘identifying’ about 30 of the detainees at Guantánamo as being associated with Al Qaeda. It is also now public, and undisputed, that al-Qahtani was tortured while in custody at Guantánamo.” (A leaked classified log of al-Qahtani’s 60-day interrogation, excerpted by Time magazine, can be viewed at http://www.ifa.hawaii.edu/faculty/jewitt/interrogation.pdf.)

During the Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) hearing, Falkoff reports, Adnan was never allowed to see the evidence against him. At first glance, this charge appeared to be contradicted by “The Guantánamo I Know,” an op-ed piece in The New York Times by Colonel Morris Davis. “Each accused receives a copy of the charges in his native language,” he wrote. An accused “may represent himself or have assistance of counsel; he is presumed innocent until guilt is established beyond a reasonable doubt; he is entitled to assistance to secure evidence on his behalf …”

But, notes Falkoff, Davis was referring to the “military commissions” system that detainees would face if they were charged with a crime. So far, only 10 out of the hundreds of detainees at Guantánamo have been charged with crimes to be tried before a military commission; each was thrown out by Supreme Court action. Some of the 10 were charged again, says Falkoff, “but with one exception those charges were all thrown out again by the military commissions’ judges themselves.” (That one exception was David Hicks, the “Australian Taliban,” who pleaded guilty to a charge of providing material support for terrorism, and served his nine-month sentence in Australia.)

The Pentagon has said it would prosecute “at most 60 to 80 of the prisoners,” says Falkoff. As a result, none of the others are likely to have a real trial—only the CSRT, which he calls “a kangaroo court if ever there was one.”

The military refused to investigate Adnan’s claim that he had been seeking medical help for his head injury in Afghanistan, on the grounds that “the request was untimely and the evidence was not readily available”—and that even if the evidence did exist it was “not relevant to the issue of whether the detainee was properly classified as an enemy combatant.” (Falkoff was able to obtain three medical documents supporting the injury claims from Adnan’s brother.)

Falkoff says he was also prohibited from bringing any news from the outside unless it “directly related” to the detainees’ cases. In the military’s interpretation of that phrase, Supreme Court cases dealing with the rights of Guantánamo detainees did not “directly relate” to any particular detainee’s case.

Even after the high court ruled that the detainees had the right to file habeas corpus petitions in 2004, the government argued that the petitions should be dismissed because the detainees had no rights that could be vindicated by habeas corpus. A federal judge dismissed that argument.

And when you pass by life’s familiar objects—

The Bedouin rugs, the bound branches,

The flight of pigeons—

Remember me.

—From “I Write My Hidden Longing,” by Abdulla Majid Al Noaimi.

Falkoff was already representing Adnan when the CSRT hearing took place in October 2004—nearly three years after Adnan was taken prisoner—but he was not allowed to attend. In his place was a “Personal Representative,” a military officer expressly prohibited from having legal training, and whose interests were not exactly those of the detainee. After their one brief meeting, the Personal Representative wrote that Adnan “rambles for long periods,” adding: “He clearly has been trained to ramble as a resistance technique and considered the initial [interview] as an interrogation. This detainee is likely to be disruptive during the Tribunal.”

Needless to say, Adnan’s status as an Enemy Combatant was not changed.

For Falkoff, there is plenty of blame to go around. He has criticized the Yemeni government for failing to reach an agreement with the U.S. to repatriate its own citizens. But most of his ire is reserved for American politicians.

“The chief failing is on the part of the Bush Administration, of course,” he says. “In the name of national security, they have made a power grab seeking to marginalize the role of the other branches of government—the legislative and the judicial.

“Of course, the other branches of government are also complicit in the Guantánamo travesty,” he adds. “While in Republican control, Congress twice passed legislation seeking to strip the Guantánamo detainees of their right to a day in court.” Even the courts have, in Falkoff’s opinion, been “far too accommodating of the Administration” and too slow in issuing decisions affecting the detainees (taking more than two years, in one case).

“The whole point of our litigation, of course, has been to force the president to justify the legality of the detention of these folks,” he says. “We need an independent arbiter. The Administration refuses to admit it could have made any mistakes, though note that it has released about 400 men from Gitmo already!”

My heart was wounded by the strangeness.

Now poetry has rolled up his sleeves, showing a long arm.

Time passes. The hands of the clock deceive us.

Time is precious and the minutes are limited.

Do not blame the poet who comes to your land,

Inspired, arranging rhymes.

—From “My Heart Was Wounded by the Strangeness,”

by Abdulla Majid Al Noaimi.

On a literary level, the “crystallizing moment” for Falkoff came as he was reading a book of poetry titled Here, Bullet, by Brian Turner, an American soldier and poet who led an infantry team in Iraq during the early stages of the war.

“His poems allowed me to feel, to some degree, what life was like as a soldier on the ground,” says Falkoff. “I realized as I read his book that one of the chief purposes of literature is to allow the reader to empathize with another person, and it occurred to me that our clients’ poems could serve the same purpose. My clients and the other poets in the volume have had their voices silenced so far, and have not been allowed to plead their innocence in our courts of law.”

The first poem he saw was one sent to him by Abdulsalam Ali Abdulrahman Al-Hela, a Yemeni businessman from Sana’a; Falkoff describes it (in an article for Amnesty Internationalmagazine) as a “cry against the injustice of arbitrary detention and at the same time a hymn to the comforts of religious faith.” Shortly after that he learned of a poem by Adnan titled “The Shout of Death,” and after querying other lawyers, Falkoff realized that Guantánamo was “filled with amateur poets.” (Both of those poems, incidentally, remain classified, as do hundreds of others.)

The detainees’ poems, Falkoff explains, “were composed with little expectation of ever reaching an audience beyond a small circle of their fellow prisoners.” Whatever one thinks of the poems in this book—some of which struck this reader as quite lyrical and moving, others as artlessly polemical—they do give the detainees a voice.

Asked which of the 22 poems he particularly admires, Falkoff singles out two. One is Ibrahim Al Rubaish’s “Ode to the Sea.” In it, Falkoff says, “the poet accuses the sea of witnessing the abuse and maltreatment of the detainees in the prison, but instead of helping, it stands idly by. I think it’s pretty clear that this is an indictment of the world and, more particularly, of the American public, who for years now have been witness to the abusive conditions at Guantánamo and the plight of innocents there, and yet do nothing to end the injustice.”

The other is Emad Abdullah Hassan’s “The Truth,” a long and “very elusive” poem about a “Manichean struggle between good and evil.” It includes the following lines:

Inscribe your letters in the heart of a laurel tree,

All the way to the city of the chosen.

It was here that Destiny stood wondering.

Oh Night, are these lights that I see real? …

Oh Night, I am a bright light

That you will not obscure.

Oh Night, my song will restore the sweetness of Life:

The birds will again chirp in the trees,

The well of sadness will empty,

The spring of happiness will overflow,

And Islam will prevail in all corners of the Earth.

“Allahu Akbar, allahu Akbar.” Allah is our Lord.

They do not comprehend

That all we need is Allah, our comfort.

Expressions of faith can cause discomfort in those who don’t profess the same faith. When the faith is Islam, some of whose followers have used their religion as a reason to kill nonbelievers, the post-9/11 discomfort can become acute.

Does any of the detainees’ poetry, I ask Falkoff, make him uneasy? I single out the line And Islam will prevail in all corners of the Earth, even though I know I’m taking it out of context.

“This particular line does not make me uneasy,” Falkoff responds. “I imagine that dozens of the major Christian sects would express the same sentiments about Christianity.”

He makes it clear that he did not take out any lines—or entire poems—simply because somebody could take a line out of context and use it to “prove” that the poet in question hates America. While some lines “seem impolitic, especially when taken out of context,” he adds, they are not hate-filled, anti-American screeds.

“There is certainly a good deal of disillusionment in the poems,” Falkoff acknowledges: “disillusionment that America, the ‘protectors of peace’ in the words of one of the poets, would abuse the men, disrespect their religion, and hold innocent men without any charge or trial. There is occasional disdain for President Bush, though I can tell you that all of my clients are sufficiently sophisticated that they understand the difference between the Bush Administration and the American public.”

Falkoff acknowledges that the collection “inevitably suffers from some flaws,” explaining: “It is not a complete portrait of the poetry composed at Guantánamo, largely because many of the detainees’ poems were destroyed or confiscated before they could be shared with the authors’ lawyers.”

Each of those that did make it out of Guantánamo required a multi-layered translation; lyricism was not the top priority.

“Everything that our clients write to us is considered a national security threat,” says Falkoff. “We therefore have to get the Pentagon censors to approve any letter, statement, or poem from our clients that we want to make public. To get Arabic or Pashtu poems translated, we have to do it with security-cleared translators working at the secure facility in Arlington, Virginia. The plain fact is that there are very few such translators available, and none who specializes in literary or poetic translations.”

Furthermore, the military has often cleared “only the English translations of the Arabic poems, making it impossible to get ‘professional’ translations outside of the secure facility. The result is that some of the ‘poetry’—the tone or cadence of the original—will inevitably be lost in translation.”

After seeing some of the poems published in Bookforum, an editor at the University of Iowa Press approached Falkoff and asked him if he had thought about putting a manuscript together. And so Poems from Guantánamo was born.

“They have been very gung-ho about the book,” Falkoff says, “even though they’ve received their share of harassment for publishing a book of poetry by ‘terrorists.’”

Poems from Guantánamo came out in August to mostly positive reviews (if you don’t count hostile bloggers calling Falkoff a “useful idiot” and worse), and is in its second print run after selling out its first printing of 5,000 copies. Robert Pinsky, the nation’s poet laureate from 1997 to 2000, wrote: “They deserve, above all, not admiration or belief or sympathy—but attention. Attention to them is urgent for us.”

Among the more thoughtful reviews was one by Meghan O’Rourke in Slate, though even she found that the poems are less interesting as works of art than in the way they “restore individuality to those who have been dehumanized and vilified in the eyes of the public.”

In a review for The New York Times Book Review, Dan Chiasson wrote that “Falkoff and the other lawyers behind this project have acted in enormous good faith and some day will be recognized for their legal work as national heroes.” But Chiasson also cynically suggested that Poems from Guantánamo should have been subtitled “The Pentagon Speaks,” given the artless quality of some poems, and that the book must actually be “some kind of public relations psych-out, ‘proof’ that dissent thrives even in the cells of Guantánamo.”

That’s a cheap shot, though I agree with him about one poem, Martin Mubanga’s “Terrorist 2003,” which sounds like something that might have been written by Ali G (the other alter ego of Borat creator Sacha Baron Cohen). It includes such stanzas as:

Now them ask me, what will ya do if ya leave the prison?

Will ya be able to slip back into d’ system?

What ya gonna do with ya new-found fame?

An’ will ya ever, ever go jihad again?

“If any common theme unites the poems, it is a general concern with physical incarceration and oppression rather than with Islam,” writes translator Flagg Miller in the book’s introductory essay. “While at times courageous and defiant, the poets at other times express utter defeat, lamentation, and nostalgia, as well as a desire to give good advice. Perhaps most surprising of all, many of the poets share a deep strain of romantic longing …”

Miller suggests that the poems should be viewed as contemporary examples of Muslim prison poetry—habsiyya, which “draws on the traditions of Persian love poetry” to suggest the author’s suffering—as well as traditional Arabic qasida verse.

Knowing what the stakes are, “the poets struggle intelligently, with what resources they have, to engage the sympathy and responses of the broadest possible audience,” Miller adds. “Pinioned impossibly in the context of a global war on terror, they seem to realize that a vocabulary of Islamic militancy is poor currency for such ends, even if it were available to given detainees. Instead, the poets strive for a language that is more likely to win advantage: the discourse of universal human rights.”

They are artists of torture,

They are artists of pain and fatigue,

They are artists of insults and humiliation.

—From “Hunger Strike Poem,” by Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif.

In December 2005, Congress voted to strip the detainees of any habeas corpus rights, and six months later passed another law—the Military Commissions Act of 2006—that affirmed its intention to take away the habeas rights of detainees who had already filed their court petitions. (The Supreme Court agreed to hear the lawyers’ challenge to the constitutionality of the two Congressional actions, and was scheduled to decide sometime this fall what constitutional rights the detainees have.)

When Falkoff visited in April 2006, Adnan told him he had lost hope of ever being released. By then, he was in bad shape: one eye swollen shut, the other a “sickly black-blue.” He had been beaten and sprayed with pepper spray—apparently, he said, for having stepped over a line painted on the floor of his cell while his lunch was being passed through the food slot of his door.

“Perhaps you can kill yourself without realizing it,” Adnan told Falkoff. “If you don’t realize what you’re doing, maybe you won’t end up in hell.”

Two months later, three detainees committed suicide. Navy Rear Admiral Harry B. Harris termed it an “act of asymmetric warfare aimed at us here at Guantánamo.”

Early this year, Adnan began a hunger strike, which the military countered by force-feeding him a liquid nutrient, inserting a tube up his nose and into his stomach.

In his final journal entry this past May, Falkoff noticed that the shackled Adnan appeared “more sedate than usual,” and wondered if the military had “silently slipped some meds into the liquid nutrient they force-feed him.” There’s no way of knowing, since Falkoff was not allowed to see his medical records.

Maybe, I think to myself, it’s for the best that they are feeding and medicating Adnan by any means necessary. Maybe this will keep him from trying to escape from Guantánamo by the only way that seems possible to him. It’s growing hard for me to keep his faith in our legal system alive. Right now, it’s hard for me to keep my faith in the legal system alive.

As I prepare to leave, Adnan has one last thing to say.

“Death,” he tells me, “would be more merciful than life here.”

Falkoff is now in the academy, teaching. The last time he tried to visit Adnan and his other clients in Guantánamo, his request was denied. He has dedicated Poems from Guantánamo to the detainees—“my friends inside the wire,” he calls them, adding: “Inshallah, we will next meet over coffee in your homes in Yemen.” He has been to Yemen twice before, and the prospect of going there again doesn’t faze him any more than the prospect of taking on his government in court.

“I know to a near certainty that I will see all of my clients as free men,” he said in July. “The Guantánamo litigation has been draining, distressing, and in many ways disillusioning. But my clients are not terrorists and they do not deserve to be in detention for even a day. I refuse to believe that they will remain behind bars for long. In fact, the first of my clients was repatriated to Yemen [in June]. The others will, I feel confident, soon follow.”

He sounded slightly less upbeat on September 19. That was the day the Senate voted on a bill that proposed to give the detainees habeus corpus rights to challenge their detention. Though six Republicans joined with 50 Democrats to vote in favor of it, it still fell four votes short of the 60 required for cloture.

“It’s a tremendous defeat at the hands of the Republicans,” said Falkoff when asked about his reaction. “It just points out how pathetic the Democrats were last year, when they were unwilling to put themselves on the line by filibustering passage of the habeas-stripping bill in the first place.”

Not everyone will agree with what Falkoff is doing. But whatever his detractors say, his motivation has something to do with patriotism.

“I love our country because we are a beacon for human rights, the city upon the hill, and adherents to the rule of law,” Falkoff says. “The lawless detentions at Guantánamo undermine everything that makes our country great.”