Consider the titles: “Captain Ahab Stumps the Bartender By Asking Him If He Knows How to Make a White Whale.” “Robert Johnson Keeps the Hell Hound Waiting.” “At 1:30 in the Morning, Kafka Confesses That He Has Always Wanted to Be a Bartender.” “The Queen of Hearts Orders a Sidecar and Asks the Bartender What Happened to Her Tarts.” And there are plenty more where those came from.

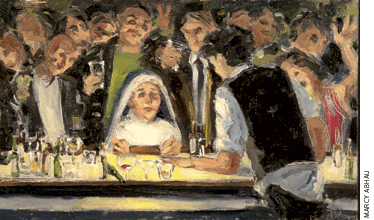

Behind each title is a painting, and behind each painting is a story. And behind each story stands a bartender: mixing drinks, dispensing banter, and taking in the nightly dramas and tableaux.

Back in the 1970s, Marcy Abhau CW’72 GFA’80 was a student at Penn and a bartender at La Terrasse. The world was different then, and so was La Terrasse, the well-known Sansom Street restaurant that once drew countless students and professors and riff-raff to its well-stocked bar, fine French food, and candle-lit tables.

Abhau got a lot of stories during her nights behind the bar: some poignant, some hilarious, some just odd. But when she first tried to put them onto canvas, her painting teacher, the late Neil Welliver, told her: “I think these are too hard for you.”

So she put those early efforts away and worked at her craft—painting landscapes, in keeping with the esthetic terrain of a department dominated by legends like Welliver and Rackstraw Downes. But she couldn’t let go of those early drink-soaked images.

“I started thinking about how I could possibly paint my experience of being a bartender,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘I don’t want to do journalism; I don’t want to paint how everybody looks now and get caught up in hairstyles and all that; I don’t want to get caught up painting a sociological study of these people.’”

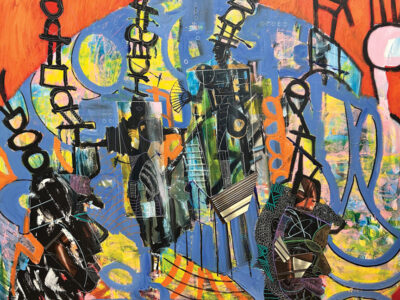

About five years ago, “my imagination exploded suddenly with images of ‘bartending moments’ that fit particular characters from the literature, music, theater, fairy tales, and television programs that I had absorbed growing up as a baby boomer,” she writes in a brief essay for the series. (The series is titled, appropriately, “Behind Bars,” and it recently hung at the Catherine Starr gallery in Philadelphia.) The “quarreling married couple” she remembered at one end of the bar suddenly transmogrified into Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler, then to George and Martha from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The elegant gentleman at the other end of the bar suddenly presented as Franz Kafka.

The images “rushed out of my imagination and into my sketch book,” she notes, and from those 75 pencil drawings have evolved nearly as many paintings, some large; others quite small. Though her approach falls under the heading of Painterly Realism—drawing on such disparate figures as Fairfield Porter, Edward Hopper, Velazquez, Titian, Daumier, and Goya, as well as Impressionists like Manet—the scenes take on a new dimension through the transforming filters of her memory and imagination.

“Since I work completely from memory,” she notes in her essay, “I have to use the knowledge acquired during three decades of painting and drawing so that I can conjure up the light, space, and body language that will express moments that by turns are silly, sweet, sad, or just bizarre, since that’s the range of emotion that takes place in every bar every night.”

One of her first painting stories—too long to tell here—involved a quiet young grad-student couple; the high-spirited Judy Wicks (then La Terrasse’s manager, now owner of the nearby White Dog Café); three burly members of the Dallas Cowboys; a lot of alcohol; a flying glass … Yet when Abhau painted it, the football players were transformed into real cowboys, anachronistically inserted into a vaguely European, 19th-century bar. The effect is dreamlike, even surreal: a sort of Mystery and Melancholy of a Bar.

“It’s kind of a reference to what a bartender just has to deal with, whatever comes up,” she explains. “So if two cowboys come in off the plains and tie up their horses and ask for whiskey—as long as they’re polite, you give it to them, because you don’t know where they were before.”

Not all the paintings, by any means, are derived from her own personal experience. After rereading The Catcher in the Rye and finding herself “incredibly moved by it,” Abhau painted “The Bartender Flags Holden Caulfield and Tells Him to Go Home.”

“Holden Caulfield was clearly having a nervous breakdown,” she says emphatically. “Yet nobody ever said, ‘Holden, I’m calling your mother—you look like shit.’”

Interestingly, the bartender in her paintings is always a man. Abhau was aware of the irony of that transformation, but eventually came to grips with it. “Now I understand that, for me, the archetypal bartender is a guy,” she says, “and besides, if I had put a woman in the paintings as a bartender, it would have totally changed the dynamic. There was a universality to these paintings that I didn’t want to lose by putting in a woman.”

That universal quality gives a particular resonance to the paintings. “When I began them, I thought they were about the crazy times we had in one particular bar in one particular time,” Abhau writes. “Now I know better.”

—S.H.