Career? Home? Guilt. Help!

By Miriam Arond

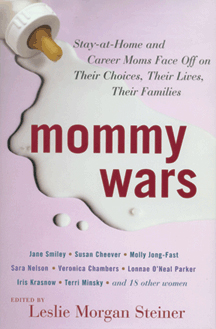

MOMMY WARS: Stay-at-Home and Career Moms Face Off on Their Choices, Their Lives, Their Families

Edited by Leslie Morgan Steiner WG’92.

Random House, 2006. $24.95. Order this book

One would hope that 30 years after women began streaming into the workforce in unprecedented numbers and with 60 percent of moms now employed outside the home, there would be not only a general self-acceptance but tolerance among mothers regarding whatever job path they take. Yet after I arrived at Child magazine six years ago as editor-in-chief, I was astonished to discover how judgmental and critical mothers are toward one another. Yes, there was an occasional supportive “Let’s all be friends” letter in response to articles we ran on choosing not to breastfeed, finding childcare, and returning to work, but for the most part there was a tremendous amount of self-defense in action. Of course—why was I surprised? I myself had found the decision to go back to an office, after having written a book that allowed me the flexibility to be home with my two young children, so conflict-laden that I entered therapy. And it’s obvious from the letters published in the March/April 2006 Gazette in response to Julia Yue Zhou’s essay “The Times and the Times” [“Notes from the Undergrad,” Jan/Feb] that I’m not the only Penn graduate who gave a great deal of thought to how to navigate the tricky terrain of work-family balance. What becomes clear in Mommy Wars, a recently published collection of mother-written essays edited by Leslie Morgan Steiner WG’92, is that, while the gap between mothers who stay home and those who work outside the home is still emotionally charged, the turmoil—the mommy war—is, in truth, internal.

There are some very accomplished contributors to Mommy Wars—including Susan Cheever, Jane Smiley, and Molly Jong-Fast—but the essays are not notable for their literary merit. What they do deliver are women’s voices, mothers’ voices, voices that too often stay silent but are so very important for women to hear. And these voices express the range of women’s feelings—their ambivalence, struggle, guilt (or self-consciousness about not feeling guilty), and the comfort that comes with finding an individual solution that offers inner peace, at least for the moment.

The power of this anthology, part of a genre that took off with the 2003 success of Cathi Hanauer’s The Bitch in the House (a collection of essays about motherhood, marriage, and sex), lies in the honesty of its contributors. Sandy Hingston writes about the joy she feels at returning to work once her son enters kindergarten … until he starts acting up in school. She automatically goes into guilt mode (“if I was a real mom, there for him every day at pickup and not just half the time, he wouldn’t be hostile and impatient and sarcastic and rude”). Hingston also recognizes that what makes her so good at her job—perfectionism—is what makes her so problematic a parent at home. Dawn Drzal, a stay-at-home mother who suffered a bout of postpartum depression, writes, “I tried not to feel suicidal about the fact that I—who had recently edited books about consciousness and complexity theory—was reduced daily to helpless weeping by the challenge of what to pack in a diaper bag.”

The book touches all chords, including the strain of being subsidized by a breadwinner spouse after years of earning your own money, the satisfaction that comes from spontaneous moments resulting from being at home full time, the annoyance of being overlooked at dinner parties because you’re not engaged in an “exciting” career. “I find it odd that I’d generate far more interest if I said I raised dogs or horses or chinchillas, but saying, in effect, ‘I raise human beings’ is a huge yawn,” writes Catherine Clifford.

What many of the contributors come to realize, even those who are totally invested in their personal decision regarding whether or not to seek outside employment, is that there is no simple formula for raising a happy, productive child. As Clifford says, “A good mother is a good mother, working or not, just as a crummy one is crummy whether she’s home all the time or hardly at all.”

Actress Bette Davis has often been quoted as saying that old age is not for sissies. I’d amend that to read, “Motherhood is not for sissies.” In her essay Jane Juska writes, “Children are not born to provide balance. Children are made to stir us up, to teach us how angry we can get, how scared we can be, how utterly happy, happier than we’d ever imagined was possible, how deeply we can love.”

Any reader coming to Mommy Wars looking for answers will be disappointed: The underlying message is that there is no simple solution or shortcut to negotiating and making peace with your own personal journey. Of course, there are many involved dads who would claim that their struggle is similar, especially now that research shows that they are just as stressed as moms about their dual work/family responsibilities. But that’s a whole other book …

Over the years, I’ve done it all—researched and written a book from home, worked part-time in an office, taken a job hiatus, and worked full-time. Each career variation entailed its own practical and emotional challenges. Each was demanding in different ways. In every stage, it was having a friend with whom I could share my feelings that was most helpful. Mothers are so often victims of isolation, certain that their experience is theirs alone. Mommy Wars offers the support and reassurance that all mothers need—whatever path they take. Now if only we can be kinder to ourselves—and each other.

Miriam Arond C’77 is editor-in-chief of Child magazine. She and her husband, Samuel L. Pauker M’80, coauthored the book The First Year of Marriage: What to Expect, What to Accept & What You Can Change for a Lasting Relationship. They are the parents of Sarah and Elizabeth.