A unique collection of 9,000 photographic slides offers a glimpse into the solo journeys of a singular woman.

One image of a mountain range washed in the milky blues of dawn merges into the next, and then the next, each time the perspective drawing in a little tighter, as in a Ken Burns documentary. The plummy voice of the photographer mellifluously narrates the scene. “In the very early hours of the morning after my arrival, I climbed to the Shankaracharya Temple, seen vaguely at the top of the mountain,” says Mary Binney Wheeler. “I had to climb 1,000 steps to get there,” she continues, her voice dipping into a dreamlike trance. “From the site of this ancient temple, I looked down on the beautiful valley of Kashmir. Below was the serpentine Jhelum River…”

The slideshow progresses, hopping from this misty mountain to the placid river banks, lined with wooden buildings and picturesque barges, to a stately building marked by a dramatic finial. “This is the Jamia Masjid, built in 1404—it is the largest mosque in Kashmir,” Wheeler says in the voiceover. “On the left, we glimpse the Hari Parbat Fort over the wall of the mosque … [Here is] a Muslim cemetery at the foot of the fort. Gravestones are placed so that they point toward Mecca. When the gravestone has a depression on the top, it is the grave of a lady. A man’s grave has a raised section called a pencil box. The man was supposed to have written the destiny of the lady… or so I was told.”

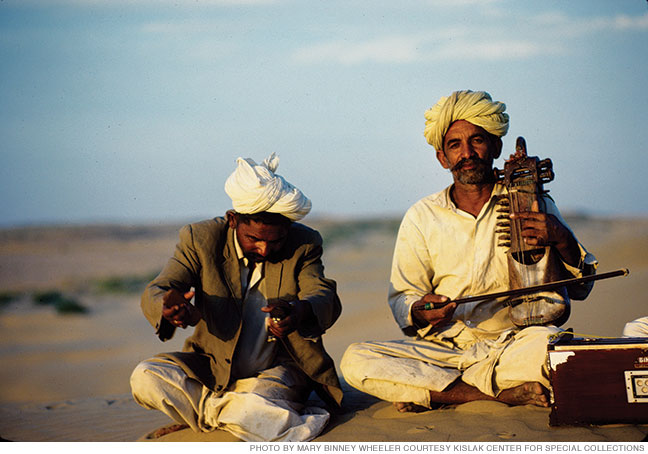

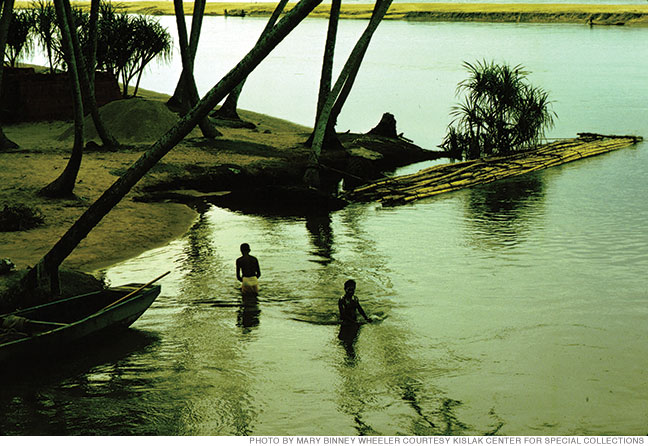

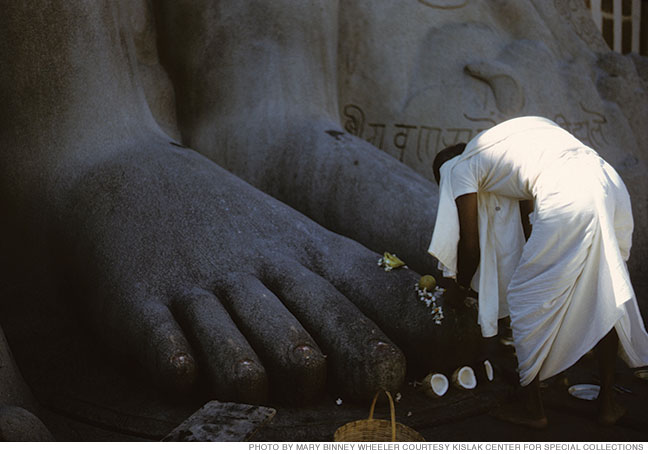

These brief excerpts of a 15-minute slideshow are just a fraction of the Mary Binney Wheeler Image Collection in Penn’s Kislak Center for Special Collections at the Rare Books and Manuscript Library (RBML). A member of a prominent Philadelphia family, the Montgomerys, Wheeler became enamored with India as a middle-aged woman, making numerous trips there and documenting her travels as she went. In later life, she began assembling the copious photographs she had taken into themes and presenting lectures to audiences as varied as local women’s clubs and visitors to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

David Nelson, a South Asia Studies librarian who has since left Penn, first approached Wheeler about acquiring the collection after hearing her speak at the Penn Museum. After Wheeler died in 1995, her daughter, Joan Mackie, went ahead with the donation, tossing in a $30,000 grant to cover the cost of digitizing the images and synchronizing old recordings of the lectures. Today, students and faculty from a wide range of fields access the online collection, which, in addition to presenting six complete lectures, features an extensive searchable database. Together, the 9,000-plus images constitute one of the largest collections of its kind in the United States, according to David McKnight, director of the RBML.

The lectures “are more than travelogues,” he says. “They are scholarly examinations aimed at unraveling the history of India and its religion and architecture. She was operating in the tradition of the romantic traveler, but given the knowledge she exhibits, she must have spent a lot of time studying the country.”

In one presentation, Wheeler offers insights that suggest a little of both. “There is a good reason why I have been in love with Rajput painting since my very early 20s,” she says. “In that romantic part of my life, I acquired a pair of art books written by Ananda Coomaraswamy, who was the first scholar to bring these enchanting masterpieces to the attention of the Western world. I became bedazzled by these books. One of Coomaraswamy’s paragraphs sealed my fate—I would love these Rajput paintings forever. I will quote: ‘Rajput art creates a world where all men are heroic and all women beautiful, passionate, and shy. Beasts both wild and tame are friends of man, and trees and flowers are conscious of the footsteps of the bridegroom as he passes by.’”

Born in 1907, Wheeler grew up on the Montgomerys’ sprawling 800-acre estate Ardrossan with her older sister Helen Hope, who famously served as the model for the character of Tracy Lord in The Philadelphia Story. As a young woman, Wheeler seemed to be able to do everything well. She studied classical piano at the Curtis Institute and while still a teenager performed as a soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Later she formed a dance company and reportedly turned down several marriage proposals from maestro Leopold Stokowski.

“Aunt Hopie was living in Villanova and having fun,” laughs Mackie. “But the person who was out there doing stuff and having adventures was in fact her younger sister.”

Still single in her late 30s, Wheeler made a bold move for the time: she adopted two infant girls (including Mackie) in quick succession. On the cusp of her 40th birthday, though, she finally met someone with whom she wanted to spend the rest of her life. But after an 18-year marriage to steel executive John Pearce Wheeler, she found herself a widow at 57—and turned again to the arts. “She could make anything—she could carve, she could paint,” recalls Mackie. “But she had never been a photographer, so she started taking serious lessons.” She also embarked on a series of journeys with other widowed friends, eventually winding her way to India, a place she had visited as a child.

“Her first trip there as an adult was in 1966,” says McKnight. “Maybe she was especially curious about it because it was such a hot destination at the time for a generation of hippies.” But while the Beatles were learning Transcendental Meditation at the feet of the Maharishi, Wheeler was meeting ordinary people and maharajahs, touring temples and palaces, and snapping thousands of photos. She would take a total of 14 trips to India and Sri Lanka through the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. The collection derives much of its value from its sheer scope—not to mention that it was the handiwork of a patrician solo woman traveler.

Mackie remembers the assemblage her mother lugged around.

“She traveled with two quite large Leicas and lots of lenses—I was always amazed at the weight of everything,” she says. “She never put them in checked luggage, she would carry them herself … no wheels!” Shooting an array of architecture, religious sites, festivals, landscapes, and people, Wheeler carefully composed a complete picture of a time and place. Let me take you there, she seemed to say about Kashmir and other locales. All will be revealed.

For Wheeler, sharing her experiences was part and parcel of her fascination with the country. While this charming Main Line matron occasionally dined on curry and entertained in saris, “mostly she kept India in her life by working on her lectures,” says Mackie, who vividly recalls her mother’s final talk. “Her church had asked her to give one of her presentations as a fundraiser, and she decided to do it in her living room, which was something like 60 feet long,” she says. “I asked if I could come along and she said, ‘Oh, darling, it’s sold out!’

“At the end of the event, there was a commotion and we rushed to the house. It turned out that after everyone had left, my mother had just invited the projectionist out for a drink. Suddenly he heard a thud, and she was gone, just like that. She literally was doing what she loved until the last second of her life.”

—JoAnn Greco