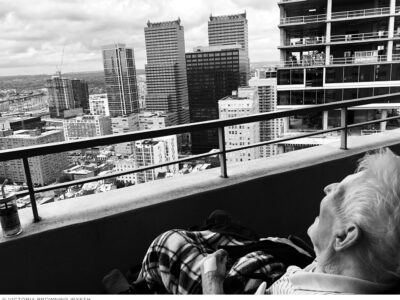

Class of ’52 | “If I were to write an autobiography,” says Florence Denmark CW’52 Gr’58, “I would call it Drowning in Paper.”

Though she says it jokingly, it’s not much of an exaggeration. At the moment, the 81-year-old Denmark is writing a book on violence against women, teaching two courses at Pace University (where she is professor emerita in residence and the Robert Scott Pace Distinguished Professor of Psychology), preparing for two addresses (one at the Eastern Psychological Association and another at the American Psychological Association’s annual convention), and serving as the International Congress of Psychology’s and the International Association for Analytical Psychology’s representative to the United Nations—among other things. “I can’t say I’m looking forward to retiring and doing nothing,” she says.

It’s hard to even imagine that. Denmark, who received the APA’s 2011 Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contribution to Psychology, has written 15 books and more than 100 scholarly articles, has presented at more than 100 conferences and invited addresses, and holds dozens of significant awards and honors. Her academic interests span the spectrum of social psychology.

Best known for her work on the psychology of women, Denmark has focused much of her research on women’s leadership, the interaction of gender and social status, cross-cultural perspectives on women, and women and aging.

“Practically single-handedly she brought recognition and respect to women’s concerns in psychology by tackling the toughest conceptual and methodological issues inherent in the interdisciplinary hybrid that is the psychology of women,” noted a 1993 citation from the APA. “She is at the top of a very short list of contemporary psychologists whose ideas and sense of mission affect the world beyond the limits of our discipline.”

Her influence reaches beyond the academic field. For as long as she’s been working in the academy, she’s also been working to help empower women—and oppressed minorities such as African Americans and gays.

But when she began her career, few psychology departments studied women, and even fewer admitted women into their faculty.

When Denmark, then known as Florence Levin, earned her bachelor’s degree at Penn in 1952, there were two separate student unions—one at Houston Hall for male students, and one at Bennett Hall for female students. The School of Arts and Sciences itself was divided in two—Denmark earned her double honors in history and psychology at Penn’s College for Women. She then moved on to psychology at the graduate level.

“I was always interested in research, and began as a graduate student in clinical psychology doing clinical research,” she says. “However, my interests shifted and I became really interested in social psychology and group dynamics—fortunately one could shift from one program to another at that time.” Her first paying job was as a graduate assistant, even though men with her academic qualifications were allowed to be assistant instructors.

In the early 1960s, while she was working at Queens College and raising three children, Denmark and a colleague conducted a study that demonstrated the positive effects of integration for both African-American and white students. When she arrived at Hunter College in 1964, she was asked, “What does your husband do?”

“I was very happy to answer that he was a dentist,” Denmark says. But due to her status as a married woman, the administration placed Denmark at the lowest rank and salary possible. Meanwhile, a similarly qualified male colleague was quickly promoted to assistant professor.

“No one said to him, ‘What does your wife do?’” Denmark says. Nonetheless, “I got promoted to full professor before he did.”

The discrimination she faced wasn’t uncommon. In fact, in many psychology departments, “women who wanted to study industrial or organizational psychology weren’t allowed to,” Denmark recalls.

While at Hunter, Denmark taught the nation’s first doctoral-level course on the psychology of women in 1970. “Students went to the dean and it finally happened,” she says. “It was really a time of concern with women and women’s issues.”

By 1973, Denmark had convinced the APA to create a new division, Society for the Psychology of Women, and she became its president. In 1975, she co-chaired the first conference on psychological research on women. And in 1983, she co-wrote the first women’s studies textbook in the United States: Women’s Realities, Women’s Choices.

Women’s psychology “really cut across all areas of psychology,” Denmark explains. Although she was a social psychologist, she says, “I had more in common with clinical psychologists, developmental psychologists who worked in this area.”

Denmark defines feminism as “equality,” adding: “We’re approaching it but we’re not there yet.”

One of Denmark’s goals is to help women get there. Mentorship is her specialty, both in her academic study and in her personal life. “Mentorship is really trying to help people along. Help them solve problems by showing them ways,” Denmark says. “Not power over others but power to others.”

As a researcher, she has published several papers on the matter. As a professor, she makes such a point to guide and encourage her students that the APA even named its Distinguished Mentoring Award after Denmark.

What drives her is a dedication to what she calls “research activism.” It’s a philosophy inspired by psychologist Kurt Lewin, one of the fathers of social psychology. During World War II, Lewin studied group decision-making, and used his research to help convince people to reduce their consumption of rationed meats.

“It wasn’t just research,” Denmark says. “It was research that led to action.”

Currently, she is studying cases of violence against women, and she hopes to find new ways to break the cycle of violence. Since men are usually the perpetrators, she wants to find ways to reach out to them. But ultimately, she says, “you may have to work with parenting, so that children don’t learn violence from their parents.

“You want to do more than just say ‘Here’s my study. This is what I found,’” Denmark adds. “You want to have [your research] lead to action.”

—Maanvi Singh C’13