A new book chronicles the performances, recording sessions, and reviews of the seminal Sixties band.

By Geoff Ginsberg

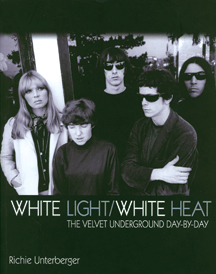

WHITE LIGHT/WHITE HEAT:

The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day

By Richie Unterberger C’82

Jawbone Press, 2009. $29.95.

Richie Unterberger C’82 first heard the Velvet Underground in the late ’70s as a freshman living in the Quad. Since no one he knew was familiar with the band, it was his pursuit of the different that led him to track down the first album: The Velvet Underground & Nico (known as the “banana album” for Andy Warhol’s iconic album-cover drawing of a banana). While that one was met with puzzlement by his peers, the less edgy and more accessible 1969: Velvet Underground Live (which he scored at the old Plastic Fantastic on 40th Street) became a minor hit in the Quad.

That live album still has a powerful appeal for Unterberger, as is clear in his encyclopedic new book, White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-by-Day, which chronicles the band and its wildly individualistic members from early artistic stirrings through heyday and breakup(s) and on to reunions and deaths and conferrals of honorary degrees. “It is not just VU at the peak of their power,” Unterberger writes of the 1969 live album; “it’s as good as any rock group has ever sounded live, and the bedrock of what might be the finest live rock album of all time.” That’s a pretty serious contention, but it’s clear throughout the book that Unterberger is objective as well as a fan. When he describes an in-concert jam that went on too long, he says simply: “Even the greatest bands fail sometimes. This is one of those occasions.” Later, discussing another live performance, he notes that it’s “almost as if the band is dragging it out like a chain-smoker might their last cigarette.”

Unterberger seems to have been born with a pair of earphones on his head and a fine-tooth comb in his hand. He has several exhaustive, well-received books about music under his belt, including The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film (an incredibly detailed history of the Beatles recording sessions); a two-volume history of 1960s folk-rock (Turn! Turn! Turn!: The ’60s Folk-Rock Revolution and its sequel, Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock’s Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock), as well as Unknown Legends of Rock ’n’ Roll: Psychedelic Unknowns, Mad Geniuses, Punk Pioneers, Lo-Fi Mavericks & Moreand its sequel, Urban Spacemen and Wayfaring Strangers: Overlooked Innovators and Eccentric Visionaries of ’60s Rock [“Off the Shelf,” May|June 2001]. Along the way he has also dabbled in travel writing for the Rough Guide series and (of all things) ethical consumerism in The Rough Guide to Shopping With a Conscience.

Now, in White Light/White Heat, he has applied his forensic detail to a day-by-day account of the Velvet Underground’s relatively brief existence. Seemingly every one of the seminal band’s gigs, recording sessions, and reviews are chronicled. To call it densewould be an understatement (it’s a coffee-table-size book with small print), but at the same time it’s a fun read. Unlike many books about rock bands, this is a story about the music, the times, and the creative process, rather than tales of excessive debauchery. And Unterberger has earned the praise of some tough critics. Howard Kramer, curatorial director of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, calls him “a tenacious researcher who writes books that make his Herculean work seem effortless.” David Fricke, senior editor at Rolling Stone and a Velvets historian himself, calls Unterberger a “rare combination in rock journalism—an incisive writer and a dogged historian.” And, Fricke adds, “the Velvet Underground deserve both.”

Perhaps the most entertaining aspect of the book is Unterberger’s unearthing of a trove of primary sources that had not previously found their way into the historical record. The San Francisco Public Library has a large but completely un-catalogued collection of underground newspapers, and he spent weeks looking through every bit of microfilm. He found reams of obscure reviews and articles (some prescient, some hilarious), as well as advertisements for albums and concerts. The debate originally wasn’t so much about whether the Velvets were good or bad, but about whether they deserved to exist at all.

“Rock criticism was in its infancy and there was no frame of reference for them,” Unterberger says. That the band’s sophisticated subject matter had been dealt with in literature for centuries meant nothing. Rock music was not “adult” at that point, and the very idea of singing about something like heroin (even though the song was not “for” or “against,” it was just “about”) was considered an outrage. Completely overlooked by most critics was the fact that Lou Reed, the band’s main creative force, was also writing some hauntingly beautiful songs.

“As a songwriter Lou is often extremely romantic and compassionate,” Unterberger writes. The Velvets have a “purity, honesty and multi-dimensionality—it’s not just the strength of the songs—it’s the variety and balance of the songs.” Furthermore, “what seems simple at first contains several layers of ambiguity underneath … there is a duality at the heart of many of his songs, which address the different sides of various personalities and the hidden inner lives that reveal themselves when they’re … viewed from alternate angles.”

Eventually the critical tables turned for the band, even as they continued to have no commercial success whatsoever. Their albums often did not make the top 200 in an era when there were barely 200 new albums out at a time. By 1970, nearing the end of their run, the praise (as recently discovered by Unterberger) was breathless. Lenny Kaye in The New Times: “The Velvets are probably the most creative band in America today, dealing in an area which most other groups studiously avoid whenever possible: Life.” And in July 1970 the early gay publication Gay Power: “Maybe you are, as everyone says, far ahead of your time—but we’re catching up with you and isn’t it nice?” Ironically, Lou Reed would leave the band a few days later, at which point the Velvets were done as a serious concern.

Today their influence is unquestioned, and acknowledged by everyone from REM to Mick Jagger; their music is viewed as high art and classic rock and roll. (Reed, the noir--est of them all, has cavorted with world leaders ranging from Bill Clinton to Czech President Václav Havel.) While White Light/White Heat is a fascinating look into the creative process of a band whose music transcended its era, it also provides a rare window into the 1960s. Among other things, it shows that as late as 1967, the country was still more American Graffiti than Woodstock—and that the Velvet Underground were equally out of step with both eras.

Geoff Ginsberg C’91 is a freelance writer living in Philadelphia. He remembers Richie Unterberger’s encyclopedic knowledge of baseball stats at Bala Cynwyd Junior High School, though they did not know each other then. He has also seen the Velvet Underground live.