In the soaring space of the Penn Museum’s Chinese Rotunda, waiting for the music to start, people in the audience touched their throats, testing the instruction sheets’ directive: Always read to yourself in an unvoiced whisper (if you place your hand on your vocal chords while whispering, you shouldn’t be able to feel any vibration). (It’s true.)

We were in the audience for Black Angels and Secrets: An Extraordinary Evening with the Daedalus Quartet, a January 13 concert—Friday the 13th, not coincidentally—presented by Penn’s music department, Bowerbird, and the Museum. The evening featured the University’s resident string ensemble performing works by three Penn-affiliated composers that took dramatic advantage of the unusual acoustics of the 90-feet tall, domed rotunda.

The concert opened with the world premiere, commissioned by the Daedalus Quartet, of lens flare from Alpha Centauri by Joshua Hey, a doctoral candidate in the music department. The title, Hey explained in the program notes, “conjures a symbolic web associated with the cinematographic technique as applied to the closest solar system to our sun: dislocation, darkness, infinity, cold, the expressivity of distortion, space, light, weightlessness …”

Next—the Friday the 13th connection—was Black Angels: Thirteen Images of the Dark Land for electric string quartet , a Vietnam-era work by George Crumb Hon’09, Annenberg Emeritus Professor in the Humanities, whose score is inscribed: “finished on Friday the Thirteenth, March, 1970 (in tempore belli).”

This disturbing and riveting composition, which drew its title from a common depiction of fallen angels in early paintings, “portrays a voyage of the soul” through three stages: “Departure (fall from grace), Absence (spiritual annihilation) and Return (redemption),” Crumb wrote, adding that the “amplification of the string instruments … is intended to produce a highly surrealistic effect” and that this effect is “heightened by the use of certain unusual string effects.”

In addition to passages that mimicked the buzzing whine of a swarm of insects, those effects included musicians tapping the strings of their instruments with thimbles, striking gongs and playing them by drawing the back-side of the bow across the gong-edge, and using their bows to play on a “glass harmonica” made of water-tuned crystal glasses. The music’s otherworldly impact was further reinforced by the striking lighting design—which threw the musicians’ shadows up the wall of the rotunda behind them as they played like angry, wildly gesticulating spirits.

After intermission, the quartet was joined by several guest string musicians, a saxophonist, and a soprano singer—not to mention the “whispered voices” of the 150 or so people in attendance—to perform Tonight We Tell the Secrets of the World, a “whisper play” by Scott Ordway G’11 Gr’13.

This was the “first reprise” of the piece, which had been commissioned by the Museum with support from the American Composers Forum, and had its world premiere there in 2016. According to Ordway, it was inspired in part by the Museum’s extraordinary collection of ancient writings—and his first experience of the acoustic magic of the Chinese Rotunda, which “creates an extreme, prolonged reverberation, allowing sounds to sustain, to travel, and to be reflected in unusual ways.”

Each audience member received a handout with a unique text addressing “three universal human themes: love, death, and god.” We were divided into sections—left, center, right—and told to start reading when a light was projected on the wall behind the musicians; red for love, blue for death, yellow for god. When you whisper your text, you are not asked to “perform,” or to direct your whispering to anyone else , the instruction sheet warned . Only the sum of our individual experiences will create a performance.

The texts in the left “love” section, where our party was seated, were adapted from Layla and Majnun, a 12th-century work by the Persian epic poet Nizami Ganjavi, whose tale of thwarted lovers shares elements of Tristan and Isolde and Romeo and Juliet.

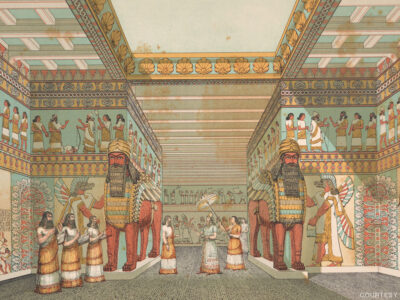

The “death” section drew from inscriptions from the pyramid of King Unas at Saqqara, Egypt (2300 BCE) and the Book of the Dead of Ani (1250 BCE), while the “god” section drew on Sumerian creation myths from 3300-2000 BCE.

At first, as the musicians began to play, the audience’s response was hesitant, self-conscious. Anticipating which light would go on next— Red! no, it’s off now; is that blue? Where’s yellow?—made it difficult to concentrate on the music. But gradually the sound built, a collective, sibilant murmur that did become a part of the performance, the ancient stories bouncing off each other and the walls of the Rotunda along with the music, fulfilling Ordway’s artistic intention:

“By working with these experts to gather texts from different cultures, and then organizing them according to universal themes, we are reminded of how deeply these themes connect to our basic humanity.”