David L. Ulin C’84 and Paul Kolsby C’84 have both forged successful literary careers in Los Angeles— Ulin as an author and book critic, Kolsby as a movie producer and television screenwriter. But a little more than 20 years ago, when they decided to co-write a serial novel about an earthquake predicted to decimate Hollywood in the old alt-weekly newspaper Los Angeles Reader, they sometimes felt more like college kids winging an assignment at the last minute.

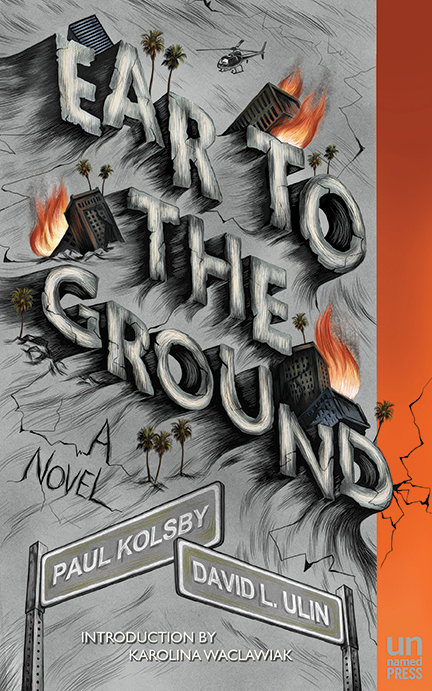

Ear to the Ground was published for 38 consecutive weeks from 1995 to 1996, with the two scribes usually taking turns churning out the chapters. But for all the self-deprecation, they’re also quite proud of the finished product—a fast-moving, biting satire that fuses the (mostly made-up) science of predicting earthquakes with the greed of Hollywood trying to capitalize on “The Big One” by rushing to produce a big-budget disaster film.

That’s why, after 20 years of the book sitting in a box in Ulin’s garage, the two recently revived it and, after taking a good meeting over tacos, sold it to a local publisher named Unnamed Press, which released it as a paperback last spring.

“The first question was, ‘Do you still have it?’” Ulin says. “It’s 20 years later, several generations of software later. Paul asked if I still had the files and I said, ‘Yeah, I do.’ So I put them all together into one master file and sent it to Paul and we both read it. And it was pretty readable! I wasn’t expecting anything. In the back of my head, I had always sort of had this idea that one day we’d make it into a book. But when we read it, it was like, ‘Oh this is pretty good, let’s see if we can find someone to do it.’”

It’s understandable why the project had, until recently, been forgotten by its creators, not to mention the rest of the world. Los Angeles Reader folded six weeks after their last chapter was published—“We were not the direct cause of the folding of the paper,” Kolsby deadpans—and the two have since bounced around between other projects. After writing and producing movies, Kolsby is now working as a television screenwriter, currently on the Netflix show Ozark, which features Jason Bateman and Laura Linney and is scheduled to debut later this year. And Ulin went on to become a book editor and book critic for The Los Angeles Times while authoring 10 books of his own, most of them nonfiction.

But as their careers took them to different places, Ulin and Kolsby always remained close, continuing a friendship that began when both were freshman at Penn, searching for ways to fit in. Back then, Ulin was a self-admitted “malcontent” who wore his hair down his back and felt “isolated” while living at King’s Court English College House and trying to avoid the Wharton “Reaganites” reveling in the 1980 presidential election. Kolsby was briefly on the wrestling team and taking “all the wrong classes.” But soon enough, both discovered a home in Penn’s arts community, running in similar circles—Kolsby performing as a theater major and Ulin plumbing literature as an English major.

“Once I found a community, I found a place I really belonged,” says Ulin, who seriously considered transferring before he met a young actress named Rae Dubow C’84, who later became his wife. “I remember having no idea that people could do the arts professionally,” Kolsby adds. “It was never something I saw. When I got out of my alcoholic stupor, I found theater and latched on.”

After graduation and shuffling through different gigs on the East Coast, Ulin moved to Los Angeles in 1991 (in large part due to his wife’s acting career) with Kolsby arriving a year later as the “most naive, wide-eyed cynic you ever saw.” It was his first time in the Golden State, but Ulin helped ease the transition, offering freelance work at the Reader shortly after becoming its book editor. Soon after, the two cooked up the idea to team up on a weekly serial novel.

The two writers complemented each other well, penning chapters on their own but swapping feedback and edits and sometimes brainstorming ideas together. The chapters were self-contained but always pushed the plot forward. The two edited each other’s work, though any mistakes that slipped past them still had to be woven into the fabric of the book—after all, there was no Delete key once the Reader hit newsstands.

“There was no hierarchy,” Kolsby says. “It turned out to be a really good way to do it.” In addition, adds Ulin, the system allowed for more writing freedom because the responsibility to make everything weave together wasn’t on one person alone. “There was a safety valve built into the project,” he says. “For me, at least, it opened up the creativity, because I felt like we were writing into the wind—but we weren’t writing into the wind alone.”

Not always knowing where the other would take the story was sometimes fun and sometimes stressful. They didn’t even know how the book would end until midway through the writing process when Kolsby had an “epiphany” on a “very drunken night.” There were other challenges, too, many involving the intractable weekly deadlines (the book wasn’t either of their main gigs). Kolsby remembers scrambling to finish a chapter on hotel stationery while on vacation in France, then telexing it to Ulin in LA.

But there were also advantages to piecing the novel together the way they did—and when they did. Since the O.J. Simpson trial was going on at the time, they incorporated that sordid saga into the book because, as Ulin explains it, the goal was to make it feel very Los Angeles—which, due to O.J. and the Rodney King riots and the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, was a fitting backdrop for a disaster novel. “Southern California felt like it was coming apart at the seams,” Ulin says. “One of the challenges with writing it as a serial in a newspaper is we wanted it to be timely and reflect the city.”

Read the book now, and you may feel as though you’re taking a trip back in time. Yet many of the characters hold up well. Ulin and Kolsby both had enough local experience to effectively spoof some of the more pretentious aspects of Hollywood. (The movie that execs were rushing to film before the real earthquake was predicted to strike featured a star named “Bridge Bridges.”) They spoofed themselves, too. The struggling screenwriter who catches his big break while in the middle of a love triangle with the hero seismologist and the pretty young film executive? He’s loosely based on Kolsby when he was trying to find work before getting cut off financially by his parents. And some scenes take place at the Formosa Café, which Ulin calls “classic Hollywood.”

“I was sort of amazed we pulled it all off,” Ulin says from that bar, now renovated, two decades later. “How we managed to do it I can’t say,” Kolsby adds. “And it feels kind of balanced—the science and the Hollywood and the satire and the action. It’s a cool mix. It would make a cool little movie, I think.”

They’re not holding their breaths on that score, though, both just happy to see something they did almost as a lark return two decades later—with almost no changes.

“I’m glad it’s out in the world,” Ulin says. “My hope is that it sells, but doesn’t sell in a big cluster and disappear—and that it kind of makes its way in the world.”

Kind of like a couple of writers from Penn have done.

— Dave Zeitlin C’03

EXCERPT

Connecting Numerical Dots

Actors say they feel at home in a theater, any theater, anywhere. Chefs love kitchens, and taxi drivers live for green lights strung to the horizon. But Charlie Richter loved numbers. He lived with them, found meaning in them. Like a jigsaw puzzle, he could fit the pieces together by applying correct persistence.

Charlie printed hard copies of his numerical tables after the computer monitor began to make his eyes twitch. He lay on the Prediction Lab floor, the carpet digging into his elbows, looking at numbers. Eight-digit prime numbers, nine-digit prime numbers, ten-digit ones. He was tired, and had been considering taking a nap on the floor when he saw it. The number first appeared at the beginning of his tables, and popped up again nearly thirty pages later. A layman would never have recognized the repeated value because he would have ascribed no meaning to it. But Charlie noticed that the two numbers, expressed logarithmically, were identical—the way a guitarist finds different ways to play the same chord.

The double incidence was nothing in itself, Charlie knew, but when he applied this particular integer as a static coefficient, he arrived at a value equidistant from the perimetary, or “bookend,” members of the matrix. Charlie was suddenly able to ascertain the epicenter of a major seismic event. He felt flush then, and began to sweat. Soon the massive logarithm was entirely solvable, like a crossword puzzle, when one nagging four-letter word leads to ten others: Moments after he’d locked down the epicenter (E), Charlie had solved for the quake’s occurrence date (OD) and magnitude (M).

Months and months of struggle and discontinuity came together in a matter of seconds. He had suspected a sizable earthquake was coming, but now he knew exactly what to expect. He took a deep breath and looked over at the map of Southern California. Then, on the back of a tattered envelope, he wrote carefully:

San Andreas. D-55. 8.9 December 29th, 1995

From Ear to the Ground, by Paul Kolsby and David L. Ulin.