Dana Walrath Gr’97 was struggling to unpack the complexity of her relationship with her mother. The artist knew she wanted to use collage, but she couldn’t find the right motif to give shape to the series of pieces. Then she thought about her mother’s name—Alice—and the Lewis Carroll classic they had read together in her childhood. Alice in Wonderland, she realized,would be the perfect touchstone for portraying an increasingly indescribable situation.

That project, which began in 2010 and took six years to realize, would become Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s Through the Looking Glass, an unconventional graphic memoir published last year by Penn State University Press.

In a sense, Alice was already in Wonderland, just beginning her trip down the rabbit hole of Alzheimer’s disease. Though she was functioning too well for lockdown facilities, it was clear that she needed to live with someone when she accidentally started a fire in her apartment. A city person who hated cold weather, she moved into her daughter’s farmhouse in rural Vermont.

As a medical anthropologist at Vermont’s College of Medicine, Walrath already knew that family support is crucial for patients. She describes her field as “all the important stuff that’s very low status on the curriculum” of medical schools, such as social and familial factors that influence beliefs and practices. Walrath wasn’t always clear about how her art and writing tied in with her medical anthropology work, but when Alice moved in with her, those disparate threads of her experience began to intertwine.

The two women had unresolved issues that went back decades. Alice, an Armenian immigrant anxious to blend in, had insisted that her children follow what she perceived as the rules of American convention, and had refrained from compliments lest their heads swell. In her youth, the spirited Walrath had chafed under her mother’s attempts to quash her nature. Those complicated feelings moved into the farmhouse with Alice.

Even without any emotional baggage, caring for a person with Alzheimer’s is draining. Walrath writes that her mother insisted early on: “Promise me you will do something else when it gets too hard.” Rather than let dementia pull them apart, the two women deepened their connection during the years they lived together.

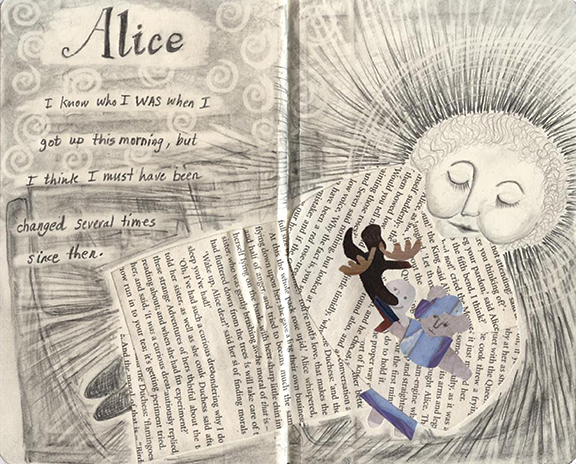

“When I started to tell our story, I knew I wanted to use a medium that someone with dementia could access,” Walrath explains. Alice, always a voracious reader, wasn’t able to focus on texts, but she could still enjoy graphic novels and memoirs. Walrath was thus led to the genre that would help her make sense of their experience.

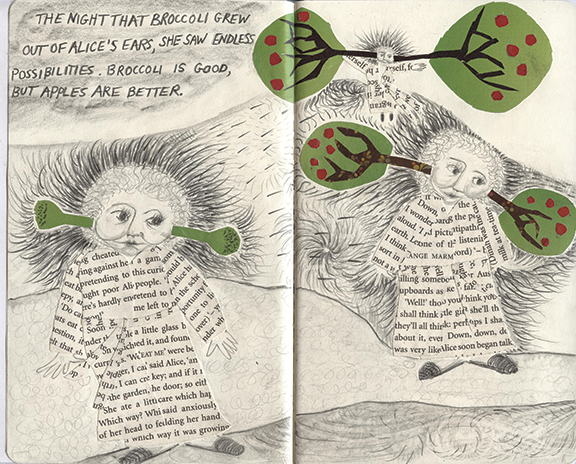

To begin the process, Walrath cut up a copy of Carroll’s text and made a collage of her mother with broccoli coming out of her ears. That day, she says, “it just unhinged, loosened up and opened everything.”

She thought she would tell the story almost exclusively in collages, with Alice clothed in the text of Alice in Wonderland. As she worked, however, she found that the story called for brief essays. Unlike most graphic memoirs and novels, Aliceheimer’s doesn’t integrate the images and the text. Each essay and image stands on its own, yet is partnered with the piece opposite. They exist side by side, inviting readers to dwell on each separately and slowly integrate them.

Walrath uses some scenes in Carroll’s story as metaphors for her mother’s experience.

“I started specifically looking for parts of the text that would correspond,” she says, such as the Lobster Quadrille to describe Alice’s tiny steps back and forth in time. “The way you get through dementia is you do what Alice does when she’s in Wonderland: she just accepts it.” Whenever her mother hallucinated, Walrath explains, “I just went with it. I didn’t correct it. It seems mean to correct it.”

In a sense, Aliceheimer’s rewrites the usual cultural narrative of Alzheimer’s and familial loss. “Alice was disappearing,” Walrath writes, yet her text describes their time together as one of healing and growth. When Alice encourages her to quit her job as a medical anthropologist and make art full-time—a risky choice she would never have suggested before the disease erased her internal governor—Walrath writes: “her loss was my gain.”

In another scene, Alice is reminded that she is Dana’s mother, and says: “I wasn’t very good to you. I’m sorry.” It was her first acknowledgement of their difficult early relationship. “Unfinished business,” Walrath writes. “That’s one of the reasons she was here living with us. But I never imagined I would hear these words stated so simply.”

Though Walrath knows that her financial circumstances and living arrangement made it somewhat easier to manage the situation, she makes it clear that there was a “lot of hard work involved in setting it up so that it wasn’t a conflict-bound situation.” Instead of fighting her mother’s dementia, she accepted the changes that it brought to their communication.

The book presents a model for human interactions that respect where people are in the moment. Throughout Aliceheimer’s, Dana accepts that her mother’s mind is often stuck many years in the past, and she engages Alice from across the decades. Of course, there were moments of frustration, Walrath says, but “it just felt cruel to be angry.”

Toward the end of their time together, Alice became increasingly violent, prompting Walrath to follow through on her promise to move her mother into a memory care facility (where she resides now). Knowing that Alice might soon lapse into speaking only Armenian, Walrath traveled to Armenia on a Fulbright scholarship, both to improve her fluency and to continue research on her young-adult novel-in-verse on the Armenian genocide, Like Water on Stone (Delacorte, 2014). Each week, Walrath Skyped with her mother from Armenia.

In bringing Alice to live with her, Walrath found the connection between her own disparate avocations: the artist, the writer, and the medical anthropologist. The striking collages and reflective essays of Aliceheimer’s offer an approach to Alzheimer’s that acknowledges the loss but also the gains. With dementia, Walrath notes, for the first time in her life “there were lots of nice compliments.” The early stages of Alzheimer’s gave Alice space to speak frankly and gave her daughter time to listen. They gave each other a chance to heal.

I absolutely loved this piece, recalling my own mother’s dementia and my sister, another Penn graduate, who cared for her so diligently for many years. I also love the idea of collage, with words and imagery (emanating from and / or reaching both sides of the brain, I would say). My own book, In Their Right Minds: The Lives and Shared Practices of Poetic Geniuses, explores the poetic words and often artistic practices of brilliant poets from the past who worked in collaborative pairs, including Blake, Keats, Hugo, Rilke, Yeats, Merrill, Plath and Hughes. If interested, see https://www.amazon.com/Their-Right-Minds-Practices-Geniuses/dp/184540789X.