President Amy Gutmann has never been to India. But her photo albums are filled with pictures of the place that was once her father’s home.

In 1934 Kurt Gutmann left Germany for Bombay, now Mumbai. “India saved my father from Nazi Germany,” Gutmann says. “It’s wonderful to go there as president of Penn, but also a very emotional moment for me to be able to return, in a sense, to one of my roots.”

When she travels to India at the end of this year, it will be both a first for Penn—no president of the University has ever visited there—and the latest in a series of links with the Subcontinent. Those include the growing enrollment of students from India; the founding of the nation’s oldest South Asia Studies program here in 1947; archaeological digs and business-education programs; and scholarly exchanges on such contemporary topics as Bollywood’s representation of the family and the effects of economic reforms begun in 1991.

After traveling to Agra and Rahasthan in late December, Gutmann will arrive in Mumbai on January 2 for the official part of her trip. There she hopes to visit the places where her father lived and worked for 14 years.

Kurt Gutmann was a college student when he saw Hitler was rising to power. “He had been apprenticing to a metallurgist and had traveled to India and Afghanistan, so he decided to pick up and leave and go to Bombay, now Mumbai,” where he created his own metalworking business, Gutmann explains. “He was the youngest of five children of a German Jewish family, and he got the whole family out and saved them from the Holocaust.”

Newlyweds Kurt and Beatrice Gutmann, who had met while he was traveling to the United States, honeymooned at the Taj Mahal Hotel in 1948.

As a girl Amy Gutmann, who was born in the U.S., corresponded with the children of her father’s former employees, she recalls. “I have these letters that say, Dear Sister Amy.”

TODAY INDIA PROVIDES the third largest pool of undergraduate applicants to Penn from outside the United States—after Singapore and Canada.

This year 202 students from Indian high schools applied to Penn, 38 were admitted to the freshman class, and 22 enrolled. “Penn is consistently the Ivy school receiving the largest number of applicants each year from students attending high school in India,” says Maryann McDonagh, assistant director for undergraduate international admissions. This academic year Penn counts 135 undergraduates and 281 graduate- and professional-school students who are Indian citizens attending classes on its visa sponsorship.

Penn’s engineering dean, Dr. Eduardo Glandt GCh’75 Gr’77, will make his fourth trip to India in January to meet with alumni, parents, and potential students. “We have a tremendous [Indian] presence at the undergraduate level, the graduate level, and on the faculty,” he says, “and we have alumni back in India who are extremely successful and some of the drivers of the tremendous explosion of the Indian economy.”

“A long time ago it was a one-way street,” Glandt adds. “People would come to this country to study and stay … Now we are in danger of losing people who go back to India. So many companies are opening research labs in Bangalore and elsewhere that we now see India not only as a source for brains but as competition for brains.”

IN 1938 Penn’s chairman of Sanskrit—a missionary’s son who had his early schooling in India—made the case for studying the region. In India and Humanistic Studies in America, Dr. William Norman Brown foresaw “a vigorous India, possibly politically free, conceivably a dominant power in the Orient, and certainly intellectually vital and productive,” then went on to ask, “How can Americans who have never met India in their educational experience be expected to live intelligently in such a world?”

What is now known as the Department of South Asia Studies was formed at Penn after World War II, growing out of a program Brown created to teach soldiers about the region’s languages and culture. Today it offers graduate- and undergraduate students both a broad exposure to the region—from its languages, literature, and music to its history, politics, and religion—and a specific strength in one of those disciplines.

With Sanskrit and eight modern Indian languages on the course register, the University offers more Indian languages than any other educational institution outside of India, according to Dr. Rosane Rocher, professor and graduate chair of South Asia Studies.

“In this country it’s considered a special achievement to speak another language,” she notes wryly. “In South Asia it’s expected that most people are multilingual.”

As the Indian economy has taken off in the past 15 years, an increasing number of students are enrolling in South Asia Studies with plans to pursue international business careers or work for non-governmental organizations, Rocher says. The program is also seeing more undergraduates who simply “want to have a background cultural knowledge of their heritage or to speak to their grandparents when they go to South Asia.”

“It’s a huge area with huge developmental potential, so it deserves attention from all Americans,” she says.

Four year before he wrote about India and the humanities, Brown traveled there to arrange an excavation in the Indus Valley, one of the cradles of civilization that had barely begun to be uncovered.

It took him a year to get permission from the Indian government to dig at Chanhu-daro—a site that is now part of modern-day Pakistan—in a project co-sponsored by the Penn Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Led by English archaeologist Ernest Mackay, it was “the first authorized foreign archaeological excavation in the Indian subcontinent,” says Dr. Gregory Possehl, professor of anthropology and curator of the Museum’s Asian section.

It was also “the first time that a small [Indus Valley] site that wasn’t a city had been systematically excavated,” says Possehl. “So we moved away from a view of Indus Civilization coming to us from big cities to a place that was not urban and turned out to be a center of craft production, especially for the manufacture of carnelian beads and the inscribed stamp seals that the Indus peoples made.”

Possehl himself came to Penn in 1973 and has excavated four major sites in the Indian states of Gujarat and southern Rajasthan, focusing on the Indus Civilization that arose there between 2500 and 1900 B.C.

His next excavation will take him to Ra’s al-Hadd, in the country of Oman, where test excavations yielded a significant amount of pottery from the Indus Civilization. “There were hints of maritime commerce in the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf during the second half of the third millennium B.C during the time that the Indus Civilization was in existence,” Possehl explains. “It’s only been in the last decade or so that we’ve come to understand that people bearing Indus pottery landed on the coasts of the Arabian peninsula from Oman all the way around to southern Mesopotamia.”

AT WHARTON, where faculty are more interested in modern-day commerce, India has been the focus of numerous programs, and its firms and financial markets have attracted the research of several scholars. “There has been a major change since the early 1990s in Wharton’s India agenda,” says Dr. Jitendra Singh, the Saul P. Steinberg Professor of Management.

This month, for example, the school will host its 10th annual Wharton India Economic Forum, “one of the premier forums in the United States where business and economic issues are discussed.”

In June Wharton faculty led the school’s first custom-education program in India with 50 executives from ITC Limited in Kolkata. India and China are the two countries Wharton is targeting for the growth of its executive-education programming, according to Dean Patrick Harker CE’81 GCE’81 Gr’83.

Wharton also collaborated with Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management to help form the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad, the country’s first private business school. “Over the past few years as the school has gotten up and running, our faculty have spent an enormous amount of time in teaching and curriculum design,” Harker says.

However, he adds, Wharton’s interest in India is as much about partnerships as it is about running programs. “We’re not only teaching there,” he says. “We’re also learning about business practices in India.”

Singh agrees. “Indian firms are increasingly evolving their unique cultures and management practices, which will be worthy of study in the years ahead.”

The current upswing in interest in the Indian economy and society followed decades of relative neglect fostered by tensions between India and the U.S., according to Dr. Francine Frankel, founding director of Penn’s Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI).

“I don’t think many people realize that we in the United States have lost more than two generations of scholars on contemporary India because of the estrangement between the U.S. and India.” During the Cold War it was difficult for American scholars to get visas from the Indian government to do work there, explains Frankel, the Madan Lal Sobti Professor for the Study of Contemporary India. “There was a presumption that [they] could very well be carrying out undercover activities.

“When that opportunity suddenly seemed to open up again [in the early 1990s], I had preliminary discussions with several senior American officials … and we thought this was a good time to try and develop a center that could nurture a new generation of scholars on contemporary India to fill that gap.”

With grants from the Ford Foundation and India’s ministry of external affairs, CASI was started in 1992. An endowment campaign that began in 2003 with a million-dollar challenge grant from the School of Arts and Sciences has raised $4.5 million for CASI—about half of what it needs to sustain itself.

“What we did was start the discussion that contemporary India is going to be a major power in the foreseeable future,” says Frankel, “and educated Americans need to know much more about the very rapid changes occurring in contemporary India across the board—in society, politics, foreign policy, international communications, technology.”

CASI has promoted these goals through scores of campus talks, conferences, and collaborative work with a counterpart institution in New Delhi called the University of Pennsylvania Institute for Advanced Study of India.

Among CASI’s current projects is an “Indo-U.S.” dialogue about shifting power alignments in Asia. The center is also examining some of the inequalities across employment sectors and states associated with India’s rapid economic growth. “Telecommunications and banking are growing quickly, for example, but agriculture is declining in many cases,” Frankel says. “We’re asking why.”

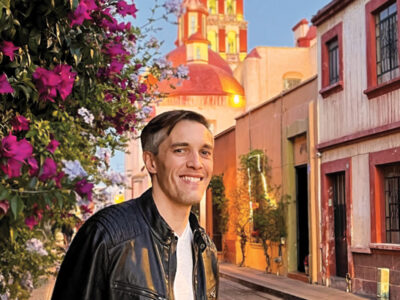

For Wharton’s Jitendra Singh, who was educated in India and the United States, the recent developments in India help bring together two important worlds: “While I still had many family members in India, my professional life was largely in North America and Europe” until the economic reforms, he says. “One of the big developments has been that the kinds of ideas we work with at Wharton, the core of my intellectual capital, is exactly what the leading Indian firms need. This has led to my ongoing involvement with India and Indian firms since the early 1990s.

“I am much more positive and optimistic about India’s future development trajectory than I have ever been,” Singh adds. “An important piece of the puzzle is the relationship between the U.S. and India, which is at its highest point now.”

One thinks that W. Norman Brown would be pleased, writing as he did about India some 60 years ago: “We shall need to reconcile our civilization to hers, to the change of both.”

—S.F.

Meet the President

Dr. Amy Gutmann will make a presentation to Penn alumni, parents, and friends during a reception at the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Mumbai on January 5.

“Over 4,000 alumni came out to welcome Dr. Gutmann domestically last year, and this year she has made it a priority to reach out to our global alumni population,” says Robert Alig C’84 WG’87, assistant vice president for Alumni Relations. “We’re expecting the same energy and enthusiasm from our international alumni.”

Gutmann’s reception kicks off the Wharton Global Alumni Forum in Mumbai on January 5-7. As the first event in the school’s yearlong 125th anniversary celebration, the forum offers “a great way not just for Indian alumni to come and gather, but also alumni and friends to come and learn about the Indian economy and what is happening today,” says Dean Patrick Harker.

Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who led major economic reforms in the early 1990s as the country’s finance minister, will be the keynote speaker at the gala dinner on January 7.

Representing the Family in Film and TV

It’s another juicy installment of the Indian soap opera Because the Mother-in-Law Was Also Once a Daughter-in-Law:

In a previous episode, Tulsi had shot her son for marrying a girl against her will and insisting upon having marital relations with her. Now, with a bitter wind whirling around her sari, our heroine stands before a statue of the Hindu goddess Durga, begging forgiveness for her “demon-like son.”

“In all the prime-time soaps the chief protagonist, whether in a positive or negative role, is almost always a woman,” explains Dr. Shoma Munshi, a Fellow of the International Institute for Asian Studies whose presentation on “Cultural Issues in Contemporary Indian Film and TV Narratives” was cosponsored by Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Annenberg School for Communication.

Women’s prominence in the soaps reflects the fact that they make up 60 to 65 percent of India’s huge TV market. The country’s 100 million television-watching households now have 100 cable and satellite channels to choose from, compared to just two state-run channels in 1990. That growth, along with Bollywood’s 3.6 billion movie-ticket sales, positions India as “an international hub for the media and entertainment sector for the 21st century,” says Munshi, a former assistant director at CASI.

The economic changes that make this possible have provoked mixed reactions within Indian society—which are then played out in popular depictions of family and conjugality, she says. Indian soap operas, for example, invoke nostalgia about the Indian joint family while puncturing it in plotlines full of “discord, property disputes, and oppressive familial hierarchies,” she says. At the same time, she notes, concerns over an “intrusion of Western values” into Indian culture have given birth to the “utopic family film” in which “duty and family honor seem to triumph over love.”

While India has become increasingly “a visible player on the global stage,” Munshi says, “in popular media representations, over and over again, there is a return to the family space. My argument is that the real and representational journey of the transnational Indian is fraught with both celebration and anxiety.”

Business Forecast

As Wharton’s Saul P. Steinberg Professor of Management, Dr. Jitendra Singh has been watching some of the trends that are putting India on the global stage. One of them is the country’s success as a destination for business process outsourcing (BPO)—or offshoring—in which companies contract part of their work to outside service providers.

“Foreign firms came to India for the cost, but they have stayed on for the quality,” Singh says. India’s share of BPO business can be broken down into what are known as low-value- and high-value-added services. On the lower end are collections and customer-relations management. On the higher end are software services, IT network management, and most recently the highest-end consulting services.

“However, the really exciting opportunities are coming up in domains like pharmaceuticals and technology,” Singh says. “Already, after the U.S., India has the largest number of FDA-approved manufacturing plants.”

As firms in other countries attempt to imitate its success, and, as the rupee strengthens against the U.S. dollar, India’s dominance as a BPO destination will inevitably fade, Singh says. “The important question for India, just as for the U.S. or any country, is how to keep improving the employability of the human talent pool, so that they can adapt to changes in the economy that are difficult to control, given global forces.”

Though Singh believes the country’s overall direction is a positive one, he notes that there are “serious challenges” ahead: India needs to continue its economic reforms to attract more foreign direct investment and make “serious investments in its infrastructure,” including roads and bridges. “Some other urgent needs include systemic improvements in primary education and healthcare, which are ideal candidates for large-scale governmental policymaking and action.”