The legendary Prince of Broadway talks about the golden age of musical theater—and his next show.

By Samuel Hughes

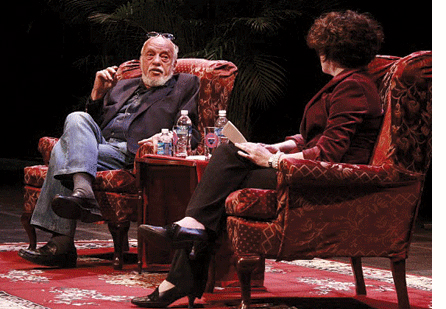

There are conversations, and there are conversations. What was billed as a public conversation with Harold Prince C’48 Hon’71 at the Annenberg Center this past December turned out to be a freewheeling exploration of the past, present, and future of American musical theater.

Hardly surprising: The 83-year-old Prince has always been one of nature’s raconteurs, and he certainly doesn’t lack for raw material. During a storied career that spans more than six decades, his producing and directing talents have earned him 21 Tony Awards, including one for Lifetime Achievement in the Theater. The list of artistic and commercial triumphs includes West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Cabaret, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd, Phantom of the Opera … the list goes on and on. (For a more detailed look at his career, see “Putting on a Show,” Nov|Dec 2000.)

Though Prince was ostensibly conversing with Rose Malague, director of Penn’s theatre-arts program—and later, in a Q & A session, with the audience—the questions essentially served as prompts for his heady blend of vignettes, ruminations, and observations. Whittling the full transcript of this conversation down to a manageable length was not easy; those interested in reading it all can go HERE.

The Perils of Star Power

I don’t think enough people go backstage and work as either stagehands or stage managers or any of that stuff. I think there’s a terrible desire to bypass all that, and be a star—be famous. But it’s a trap …

You know, Angela Lansbury is as good on film as she is on the stage. I made a movie with her: She projected. I also made a movie with Elizabeth Taylor, and I could never hear her, and I’d have to say to the cameraman, “Did she do it? Did she say it?” Because the technique had become whispery, and I found it frustrating and I didn’t care to do it anymore.

Julia Roberts sold out on Broadway. She’s wonderful on film, but she couldn’t be heard and she didn’t know what to do with her hands, and how to move.

That’s the bad thing that’s happened to Broadway. Because of an audience which has money to spend and very possibly not quite the taste that the old audience did, they will pay to see two superstars in a bad play that gets bad reviews but sells out every performance, and does a million-something every week, and then those people go away. Julia Roberts sold out every week [in the 2006 play Three Days of Rain], and Katie Holmes made a hit out of a play in a subordinate role [in the 2008 revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons]. That’s what I’m fighting, but I’m of an age where there’s not much point in fighting. And I’m certainly not going to move over to the commercial standards that have prevailed today.

Of Mentors and Men

I was mentored by two people—one knew he was mentoring me, and one didn’t. George Abbott mentored me. He thought I had a future. The other one was the only other director I ever produced for, Jerome Robbins, and he didn’t know he was mentoring me. But I watched everything. So I learned one thing from the one man, and quite another thing from the other man, and I produced their shows. Jerry did West Side and Fiddler, and Abbott did all those other shows you’ve heard about.

One thing I learned from Abbott early on that was very useful, and is more useful to me now, is to make a collaboration with someone who’s had a lot of experience and craft with someone who’s young, inexperienced, has great talent, and can jolt you into the next decade, the next century, contemporary taste. Very important. George did that with me, and with Leonard Bernstein, and [Betty] Comden and [Adolph] Green, and Jerry Robbins; he gave them all their first shows. I always like to have someone around who is new, to keep up my contemporary ante, because I tend to think about the way things were.

On Musical Roads Not Taken

I’ve never had a show I’ve turned down that I wish I had done, though I’ve loved the shows. David Merrick asked me to do 42nd Street, and I thought, “How flattering!” But I said, “I couldn’t do that; I don’t know how to do that.” He asked me to do Hello, Dolly!, because my first directing job before I was directing in New York was The Matchmaker [on which Hello, Dolly! was based], and he’d heard it was wonderful. So he said, “Why don’t you do Hello, Dolly! for me?” And I listened to the material; Jerry Herman came into my office, and I said, “It’s swell, but it’s not Hello, Dolly! She’s not a lady—‘How great it is that you’re back where you belong.’ She never went there.” And I was very didactic and stupid and literal about it. But it’s a show I adored, and I don’t think the musical Hello, Dolly! is a reflection of The Matchmaker.

After I did Evita, Andrew Lloyd Webber asked me to come to the apartment to play his next score—to hear his next score—and it was Cats. And I heard it, and I said, “Andrew, I’m the wrong guy to direct this. It’s very English, right? Grizabella is Queen Victoria and [Munkustrap] must be Gladstone, and another one must be Disraeli.”

And he just took the longest sigh in the world, and said, “Hal, it’s just about cats.” So I would have ruined it.

Lenny, Lillian, and the Book of Candide

The first show I did was Wonderful Town. I was a stage manager, so I just knew Lenny [Bernstein] as this huge force of nature, a great talent. And then when I did West Side, I was the producer, not intrinsic to what he was doing. So we didn’t get to know each other very well. When I did Candide, I visited him in Boston when he was doing the Norton lectures and told him what I wanted to do. And he said, “Go do it.” And I threw the whole book out, and Hugh Wheeler wrote the new book, and that meant that Lillian Hellman had to step aside, and she very generously said, “Sure, but you can’t use a word of my original libretto.” Because we thought she and Lenny had written two different shows. They were very close, but she had written a very political show. She was talking about the blacklists and all this stuff, and Lenny was writing a bubbly operetta, and one of the best. So Hugh Wheeler wrote the book, but the only way we could get it on was in Brooklyn, at the Chelsea Theater Center, with 13 instruments, and an audience of 150. And the word got out, and it was a huge hit, and then we moved it to Broadway. I always knew that Lenny regretted the loss of 30 instruments, and so some years later Beverly Sills talked me into doing it at City Opera, and there he got to hear 70 musicians, and I put the whole thing on stage.

And when he died, sadly enough, we were talking about doing an opera, a serious musical, an operatic musical. He wanted to write about the Holocaust, and I wanted to work with him.

The Few, the Proud, the Future

I was told on my way here that a lot of people know who [songwriter] Jason Robert Brown is, and that’s the best news I’ve had. Because I think he is one of the few futures of the American musical theater. And even though I did Parade with him, it’s my daughter who discovered him. My daughter [Daisy Prince], who did Songs for a New World, who did The Last Five Years, introduced me to him. And I think he’s spectacular, and it’s my daughter who’s directing now, which is good.

The Importance of Being Buzzed

You get a great buzz from London—with Evita, with Phantom. I’ve always felt that as successful as Phantom is—and it’s in its 22nd year—if it had opened originally on Broadway it would have been closed a long time ago, despite the audience response to it. The two years that people talked about it, and generated all this hype before we came to New York, was very important to what’s happened now. Because the reviews were good, but begrudging. And reviews are very often good but begrudging, and you have to get over them.

We opened Fiddler on the Roof in Detroit, and there was a newspaper strike, so I asked to read the reviews … and they were terrible. Variety did print a review, and it was not good at all. I sat down and wrote all my investors, and said, “Don’t believe a word of it, it’s going to be a huge success,” because I knew the audiences were flocking despite the bad reviews. We got to New York, and we didn’t get good reviews—they called it “too commercial” and all kinds of things—yet it ran 9 1/2 years, and made history. And on the anniversary of the performance when it became the longest-running show on Broadway, I printed all the [bad reviews] on gold paper, and made them into a little program, and handed them to everybody. It was very satisfying.

The Road to Paradise

Now I’m doing a show, it’s going to rehearse in New York, but open in London. Mandy Patinkin is the lead, and I’ve got a great cast, but it’s taken five years to get it up, and now I’m going to rehearse in April, and then we’re going to London, to a small theater called the Menier Chocolate Factory, which has a very prestigious reputation. And then hopefully we’ll come back to New York, with the buzz that you get from London.

It’s called Paradise Found. It’s based on a book by Joseph Roth, who was a great writer in Vienna. He wrote political [pieces] for the newspapers, and he wrote a great novel called The Radetzky March. And then he wrote a novel in Paris—he was Jewish, he’d been chased out of Vienna, and he was in Paris in 1939. Hitler came in, and he died of alcoholism. But really it was a kind of suicide. The novel [The Tale of the 1002nd Night] was published posthumously, some years later.

The plot is very simple. It’s about the Persian monarch Shah-of-Shahs at the turn of the 19th century, who had 139 wives and no sex life. And his eunuch, played by Mandy Patinkin, suggests they go to Vienna. And they go to Vienna to find inspiration, and they’re given a big ball in the city palace by Franz Josef. And they go to the ball, and the shah behaves very rudely. He walks down the stairs, having been announced by the majordomo, and he yawns, and he sits down, and he curls up in a fetal position, and he just shows every kind of arrogant boredom you can show, and all the court is bowing and starting to mumble among themselves. And then he opens one eye, and he spots inspiration in the most beautiful women he’s ever seen. And he starts to bellow, and lets terrible, fearsome animal noises out, and points to her—and he is pointing to the empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And he says to the eunuch, “I want her in my bed tonight,” and leaves the party.

So the rest of the first act is how do you fob off another girl, and how do you make the room dark enough, and how do you make the room look like a palace which isn’t the palace. And all those things they conspire to do, and the shah arrives, and goes upstairs with this girl who doesn’t remotely look like the empress—and he’s inspired. The first-act curtain is the noises of his inspiration, and the four conspirators singing gorgeous music below. The second act is, he’s leaving, and he gives the girl a million-dollar string of perfect pearls, and he goes. And the rest of the musical is about what happens to people when a million dollars is plunked in their laps.

At its core, it’s about a baron who’s using this girl, who is his girlfriend, and who’s given the task to fool the shah, and he has this girl, and he has a mistress. He’s maybe what we would equate with a certain golfer. And what happens, at the end of the show, the girl and the baron realize that they’ve always loved each other—and so that’s how we get a happy ending.