“Every single thing was a discovery,” remembers Aurélie Samson of her experience digging through the archives of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Samson, an exchange student from France who is now living in Paris, was one of nine Penn students who participated in the Fall 2006 Halpern-Rogath Curatorial Seminar. Some, like Samson, were pursuing a curatorial career, others’ interests ranged from medicine to religious studies. All reveled in the trove of “wonderful photos, funny letters, beautiful watercolors, and historic objects,” says Samson.

Their goal: putting on a show about the Penn Museum at the Penn Museum. The result, “Penn in the World,” runs through September 28. In addition to the documents, drawings, and publications culled by the students, the exhibit spotlights about 30 cultural artifacts retrieved from the museum’s expeditions dating back to the 1890s. Standouts include a scaly anteater-skin jacket from Borneo; a faience amulet from Memphis, Egypt; and a feather-bedecked headdress from British Guyana.

In the seminar, co-instructors (and husband and wife) David Brownlee, the Shapiro-Weitzenhofer Professor and chair of the Department of the History of Art, and Ann Brownlee, a senior research scientist at the museum, pick the topic. After that, he says, “everything from the themes and ideas explored to the materials chosen was up to the students. This course,” he adds, “is about learning by doing.”

Each student chose a department (such as education) or geographic specialty (like North America) of the museum, then set about mining treasures from the archives. After conducting individual research, they looked for connections to create a cohesive narrative.

“It was a very collaborative process,” says Rose Muravchick, a Ph.D. candidate in religious studies, “and since there was so much interesting material, it was a challenge to narrow the field.” Conservation considerations, as well as visual appeal, helped guide students as they chose items to build their stories.

“We ended up with an emphasis on pre-World War II,” says David Brownlee, “because that period offers a greater historic sense, and also because the artifacts looked a lot more interesting.”

The exhibit opens with a colorful array of blueprints, pastels, and charcoal perspectives from the 1890s—submissions from architectural firms vying to design a building to house the University’s growing archaeological museum, officially founded in 1877. Other intriguing entries in this section include a moody photo of Harrison Hall made by painter Charles Sheeler early in his career, and an advertisement for Guastavino tiles, an engineering breakthrough that enabled the erection of a self-supporting vaulted rotunda so an auditorium placed below wouldn’t be marred by columns.

Next, “Inside the Museum” explores educational efforts such as stories printed in The Spade, a children’s magazine, and the television program produced by the museum in the 1950s, What in the World? The show paired celebrity contestants like actor Vincent Price and sculptor Jacques Lipchitz with anthropological experts, and challenged them—via billowing smoke effects and dramatic voiceovers—to identify crudely fashioned implements and ornately carved totems.

“The museum has never been just a depository for collections,” says Samson. “It’s a historical and social institution that saw many people trying to work together around a common project: to know more about the world.”

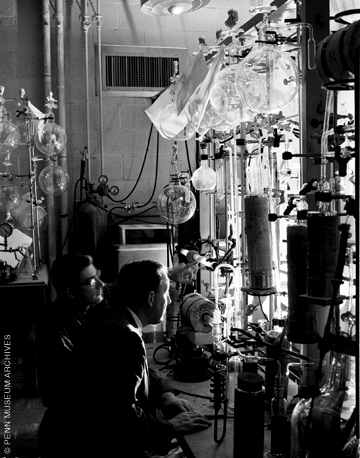

That mission is perhaps most vividly represented by the museum’s far-flung expeditions, which is the focus of the third section. It opens with an enlarged photo from 1889 of workers manually hauling and emptying buckets of sand at the University’s first excavation site at Nippur in what is now Iraq. Penn’s efforts there eventually yielded a collection of some 30,000 cuneiform tablets, the largest such assemblage in the world.

Subsequent expeditions highlighted include those to Alaska, Borneo, Peru, Crete, Memphis (Egypt), the Lenape communities of Pennsylvania, Key Marco (Florida), Guatemala, and Sierra Leone.

The selection emphasizes that not all of the museum’s work concerned ancient cultures. “There was also a lot of ‘salvage ethnography,’” says Brownlee. “Preserving cultures that were about to disappear by recording native languages, getting down native folklore, and collecting craftwork was critical.”

This section also illustrates historical improvements in the way the museum conducted its work, such as the introduction of aerial surveying in the 1940s to aid in site selection and improved documentation in the form of meticulous recordkeeping systems created to note each item’s position as it was removed from its setting.

“Before taking this class, I thought of museums as places that showcased history,” says Michelle Law C’07, currently a student in the University’s pre-health post-baccalaureate program. “I’d never considered the possibility that a museum could itself have a history.”

But the Penn Museum’s glory is not just in its past. The exhibit ends with a look at such current projects as the publication of a Sumerian dictionary based on the institution’s huge collection of tablets [“Spreading the Words,” Jan|Feb 2003], and an introduction to contemporary curatorial issues such as artifact repatriation. A map and computer station help visitors get a handle on the museum’s ongoing research and excavation sites.

For students, the learning extends to a newfound appreciation of the museum. “I didn’t know anything about the museum before,” says Samson. “That made the whole experience more exciting. Working in the archives was like its own ethnographic expedition.”

— JoAnn Greco