Inspiration doesn’t exactly strike photographer John Yang GAr’57; it’s better to say that it dawns on him.

“I only know what I’m doing maybe a year before the end of a project, so if I had to apply for grants, I’d never get any money,” he jokes one afternoon in his studio, a tidy, efficient space on the garden level of the Manhattan brownstone where he has lived since 1979.

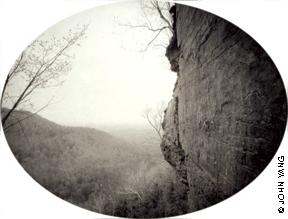

Such was the case with Yang’s latest endeavor, an exhibition of landscape photographs taken on and around the Helderberg Escarpment, a 100-foot-high limestone cliff some 15 miles southwest of Albany, New York. Entitled “Indian Ladder, A Lyric Journey,” the project only suggested itself after nearly two decades of interest in the site, and once the idea materialized the photographs themselves took additional years to complete.

The title refers to a trail first used by the Mohawk Iroquois Indians in the 1570s, the remains of which now lie within John Boyd Thacher State Park. Its original purpose was to provide access to the trading post run by Henry Hudson; today, it’s a popular hiking destination. The trail is no cakewalk. Some parts are so steep that the Indians literally built a ladder in order to pass. But the stunning prospect amply rewards anyone willing to brave the terrain. On a clear day, the escarpment commands views of the Berkshire, Adirondack, and Green mountains, and the Hudson and Mohawk river valleys.

“It’s a spectacular site,” says Yang, who first learned of the trail from a geological field guide. “It’s not on the order of anything else that you might see in the East, and it’s remarkable because it’s underneath a cliff, and on one side you have a 100-foot-high overhang with waterfalls in places, and then on the other hand you have this oceanic-like expanse that stretches off into infinity.”

Yang first photographed the trail in November of 1987, but the results disappointed him. It wasn’t until the fall of 2001 that he attempted a second shoot. A drought, however, had dried up the waterfalls that year, so he couldn’t really get down to work until 2003. Once he did, a number of logistical challenges confronted him: First, only in the early spring and late fall was the trail clear enough of undergrowth to permit the use of his cumbersome 11” x 14” large-format camera. Distance posed another problem—170 miles of it between the park and his New York darkroom, to which he had to return each night in order to change his film. It took him four years, working with characteristic patience, to complete the project.

Shown first at the Albany Art Institute and then in Chicago at the Stephen Daiter Gallery, Yang’s haunting landscapes, without in any way suggesting or attempting historical pastiche, seem not of our time.

“When people first saw these pictures they said they weren’t taken in the 21st century,” Yang remarks. “And they do have a 19th-century feel, but I didn’t do anything to make them look that way; I just took the pictures. And I put them together in the show to tell a very loosely knit story.”

Beginning at the rubble-strewn base of the trail and ending at the escarpment’s dizzying summit, the photos convey an experience of ascent. According to Yang, they represent a lyric journey, a term art historian James Cahill originally used to describe the narrative structure of Sung Dynasty poetry and painting.

“These works typically followed a distinct kind of narrative,” Yang explains. “Their theme was this idea of a recovery of a lost harmony between man and nature, and I think that idea resonates with this project.”

Born in 1933 in Suchow, China, Yang emigrated to the U.S. in 1939 after a brief stay in England. When he was 13, his father, a doctor and stockbroker, gave him his first camera while he was a freshman at the Putney School in Vermont.

Yang studied philosophy at Harvard, then decided to pursue architecture. Penn seemed like the place to do it. His thesis project, a faculty club, was designed under the supervision of Louis Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71 and earned him the Arthur Spayd Brooke Memorial Prize.

After his military service—he was stationed in Germany, and played cello in the Seventh Army Symphony—Yang returned to New York in the early 1960s to practice architecture at a firm specializing in public housing and institutional projects. There he was given remarkable freedom to design and build what he liked.

Some of Yang’s notable buildings include an all-duplex government-subsidized apartment complex on the Upper West Side of Manhattan; a police station in Astoria, Queens; an entire suite of campus facilities for Queensborough Community College; and houses for his brother and sister.

In the early ’80s, Yang stopped practicing architecture in order to devote himself to photography full-time. Since then, his efforts have yielded a handful of books and exhibitions that are best approached not in terms of their component images, but collectively.

“While my photographs can stand alone,” Yang explains, “most of them belong together. They’re like a chamber ensemble.”

Yang spent several years experimenting with an early 20th-century scanning camera, a complex mahogany-and-leather contraption originally used to photograph large groups of people. Mounted on a special mechanized tripod, the camera, a Cirkut No. 10, slowly revolves as it records extraordinarily detailed 360-degree panoramas on long, scroll-like negatives.

“It’s perfect for certain kinds of subjects where you’re not looking at them head on, but where the scene itself is all around you,” Yang explains. Two projects, “Innisfree Garden” (1986) and “The Golf Course as Landscape Art” (1989), explored this idea.

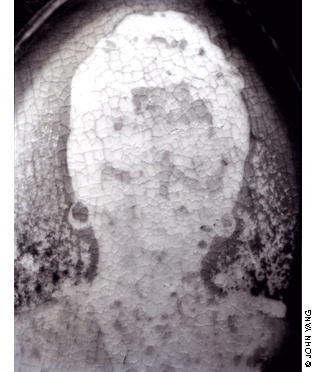

Having exhausted the scanning camera, Yang went on to write two books: Over the Door: The Ornamental Stonework of New York (Princeton Architectural Press, 1995), a survey of the architectural ornamentation in New York’s brownstones and tenements, and Mount Zion: Sepulchral Portraits (Distributed Art Publishers, 2001), poignant studies of the deteriorating photographic miniatures from the headstones of an orthodox Jewish cemetery in Queens.

“Many of these images are disquieting,” observes Yang. “So little is left of some of these faces, and I find that extremely touching.”

Today, after 60 years, Yang’s interest in photography continues as passionately as ever. He still works in his darkroom every day, reprinting many of his old negatives, and awaiting the next idea. “There is a wonder aspect that keeps me interested,” he says. “That’s why you take pictures in the first place, and why you keep on doing it.”

—David Perrelli C’01