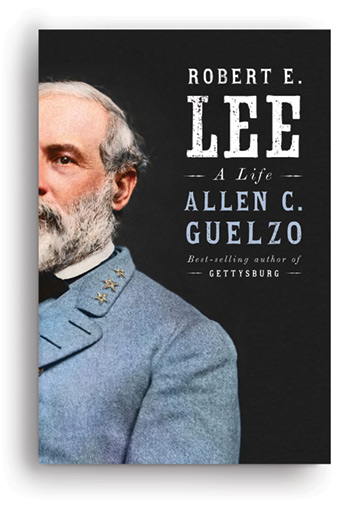

Allen Guelzo’s biography of Robert E. Lee depicts the Confederate general as a “complicated rather than complex person.”

By Allen C. Guelzo

Penguin, $35

Princeton history professor Allen Guelzo G’79 Gr’86 asks his readers to do something difficult. In the first sentence of his 2021 biography Robert E. Lee: A Life, he calls out the Confederate commander as a traitor. For many readers, that’s likely easy to swallow; the US Army colonel violated his duty to the Constitution and took up arms against his country. But later, after weaving a portrait of this “very complicated character” who was noted for his “marble dignity,” Guelzo asks his audience to have compassion for the man who opted for rebellion over duty.

One of the nation’s leading Civil War scholars, Guelzo is the author of 11 books on the conflict, Lincoln, and Reconstruction, notably the award-winning Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America.

He looks back on his years at Penn as “a glorious time, one that I treasure.” Guelzo wrote his dissertation on colonial-era theologian Jonathan Edwards. When he graduated he thought that his interest in 18th-century moral philosophy would guide his career. Almost by chance he wrote a well-received paper on Lincoln, which begat an offer to write a book on the 16th president.

“I got my hand in the Lincoln cookie jar, and I have nothing to complain about on that score,” says Guelzo, who after many years felt compelled to take “a very deep plunge” into the Civil War from the Southern point of view.

In Lee he found a man who lacked the vision to reckon with his era’s central moral issue—slavery. “It’s not that Lee is ignoble. It’s not that he is some kind of grotesque monster. That’s one of the complexities of dealing with the man. When you deal with Lincoln, you’re dealing with someone who is very complex in the sense that he has his hands in many of the currents of ideas in his time, and he’s working very hard to reconcile them,” says Guelzo. “Lee is a complicated rather than a complex person, because he sees those same currents but does nothing to reconcile them. He makes no effort to sort them out and come to some kind of coherent conclusion.”

While Lee’s noble demeanor and dignified surrender led generations of Southerners to imagine him as possessing marble integrity to the core, Guelzo instead finds a hollow man. His father, Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee III, abandoned his family when Robert was six. The resulting trauma led him to become devoted to his mother and to adopt a spotless persona. He earned no demerits at West Point, graduating second in his class in 1829. (Compare that to the flamboyant and ferocious George Custer, who years later hauled in a record 726 demerits and barely got his degree.)

Lee chose to be a military engineer and for 25 years worked on coastal engineering projects. This path suited Lee, according to Guelzo, because it offered financial security, rather than glory on blazing battlefields. At the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 he was famously quoted saying, “It is well that this is so terrible [lest] we should grow too fond of it.”

After the Civil War, during the last five years of his life when he was president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia (now Washington and Lee University), Lee made an offhand comment that revealed an inner torment that haunted him all his life. “He said the great mistake of his life was taking a military education,” Guelzo reports. “Now that is simply a bombshell of a statement coming from Robert E. Lee. That sense of regret that pervades him, that sense of loss, of absence, of never quite finding what it was he was trying to find—it just runs through so much of the man.”

The most visible sign of this confused sense of purpose came in April 1861. Shortly after the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln’s senior adviser Francis Preston Blair offered Lee command of the US Army. The meeting lasted hours. Lee showed supreme hesitation, and Guelzo untangles seven contemporaneous recollections of the event. In Lee’s defense, at the time no one knew if a long conflict would ensue.

Lee at the time wrote to an in-law that “a fearful calamity is upon us.” It dumbfounded him that “our people,” his fellow Southerners, “will destroy a government inaugurated by the blood & wisdom of our patriot fathers, that has given us peace & prosperity at home, power & security abroad & under which we have acquired a colossal strength unequalled in the history of mankind.”

Even when Lee then journeyed to Richmond, no martial fire burned in his heart. He wrote to a son that he thought assuming command of Virginia’s troops “might lead to a peaceful settlement of our difficulties” and that he might play the heroic role of “mediator, rather as an umpire & settle the question.”

Ultimately, according to Guelzo, Lee chose to lead the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy’s key fighting force, not to defend slavery or because he lusted to fight but to save his 1,100-acre Arlington hilltop estate across the Potomac from Washington, DC. He feared the Confederates would confiscate it if he declined to defect. (In the end, the federal government not only seized the property but—to add eternal indignity to Lee’s memory—established Arlington National Cemetery at the site.) “The property belonging to my children, all they possess, lies in Virginia,” Lee told his mentor General Scott in a frosty exchange. “They will be ruined if they do not go with their State. I cannot raise my hand against my children.”

“All of this,” writes Guelzo, “was done for the sake of a political regime whose acknowledged purpose was the preservation of a system of chattel slavery that he knew to be evil.”

Lee had inherited 42 slaves in 1857 when he became executor of his father-in-law’s Arlington property. Though the will bound him under its terms to free them, he kept them to help stabilize the estate’s finances, only liberating them in 1863.

Throughout his life, Lee seems to have never thought deeply about the South’s “peculiar institution.” In the 1850s he wrote to his wife that slavery—“a moral and political evil”—is “known & ordered…by a wise & merciful Providence.” Lee went on to tell her slavery does more harm to whites than Blacks and that their “painful discipline” will “prepare & lead them to better things.”

“It is one of those perfectly preposterous statements that suggests someone who is looking at Black people but not really seeing them,” says Guelzo. “On the other hand, take the thread of that and pull on it, and you learn something very interesting: slavery poisons every relationship—not just the relationship of Black and white; it also poisons the relationship of Black and Black and the relationship of white and white.”

As Guelzo sees it, slave ownership was “a Midas touch in reverse” that corroded Lee’s soul. When three of his slaves escaped—two men and a woman—and were returned, Lee ordered severe punishment. An overseer refused to whip them, but Lee told the constable who delivered them to “lay it on well.” Lee himself, according to a newspaper account, may have stripped the woman and given her 39 lashes.

That kind of brutality “was peculiar,” Guelzo believes. “It’s uncharacteristic of the man from what we otherwise know. It suggests there’s somehow a layer there that he worked over his life to conceal.”

Guelzo does credit Lee with being a keen military strategist. He invaded the North twice and tried to do so a third time, moves that held “the possibility of ending the war and achieving the independence of this people by one short and brilliant stroke of genius, endurance, and courage,” Lee later wrote. He knew that if he could break the Union’s will to fight by turning voters against Lincoln, the South might win a negotiated settlement.

Today Guelzo is working on a book about Lincoln and democracy. “It’s like I took a long journey in a deserted land, but now I’m finally back home, and I’m where I’m most comfortable,” he says. As for the hollow subject of his past scrutiny, Guelzo says “one comes away from Robert E. Lee with a sense of very deep sorrow and regret about the man.”

The recent racial protests and violence that has swept the US and the cruel divides of modern politics trouble Guelzo much in the way that slavery appalls him. “Behaving mercilessly sometimes seems like it comes natural to human beings, either because we’re easily tempted to anger and defensiveness, or we’re tempted to various varieties of self-righteousness, and we see in others’ eyes the mote and miss the beam in our own,” he says.

“I suppose I’m asking with regard about Lee not only for a sense of compassion in trying to understand the man but also some compassion in trying to understand ourselves.” But Guelzo is quick to append an addendum: “Compassion is not the same thing as condoning. Compassion is not the same thing as forgiveness.

“But at the same time,” Guelzo adds, “There can be no true will, no real judgment without that measure of compassion, because otherwise it tempts us to become monsters, and that is something I think we fail to see time and time again.”

—George Spencer