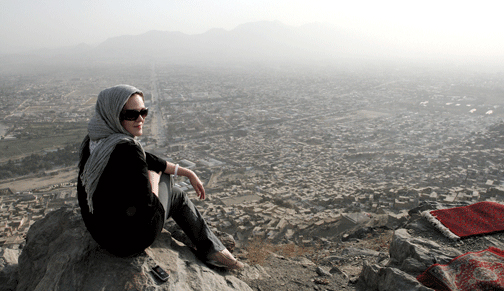

Class of ’08 | When Aleksandra Markovich C’08 stepped off the plane in Kabul, her arms, legs, and neck were draped in black clothing, and she wore a headscarf to ensure that her first steps in Afghanistan would signal respect for its culture. While her attire and knowledge of local customs helped her prepare for life in a vastly foreign and troubled country, other things were impossible to foresee—or forget.

“On Monday, a female NGO [non-governmental organization] worker was gunned down on her way to work,” Markovich emailed shortly after she arrived. “Apparently the Taliban did not appreciate her ‘preaching of Christianity.’ She worked for an organization that helps the disabled.”

Markovich was not entirely unfamiliar with life in troubled countries. While she was a political-science major at Penn, she interned for an international aid organization in Serbia, her family’s homeland.

“My experience there only cemented the fact that I wanted to pursue a career in international development,” she recalls. When a colleague from that project asked if she’d be interested in working on a local-governance and community-development project in Afghanistan, she jumped at the opportunity.

Now, as part of a private U.S. company that for security reasons asks not to be named, Markovich helps secure approval for grant projects such as literacy training, carpet-weaving training, and saffron production. By chairing review and evaluation panels that decide which NGOs will implement grant projects that receive U.S. funds, she ultimately helps women learn to read, provides books to schools, and brings clean water to communities in need. Afghans hired by the company handle the groundwork and monitor the success of the projects, which reach 11 provinces and more than 70 communities in the northern and western regions.

The challenges are often daunting. “To be able to carry out these projects, approval from the community is needed,” Markovich explains, and since some of these communities are deeply influenced by the Taliban, projects geared towards helping women are often rejected.

Asked how she stays safe when the Taliban specifically targets international development and aid workers, Markovich admits that her movements in the city are extremely limited. She can go to “internationals only” restaurants and secure rural areas, but she doesn’t walk around in Kabul, which is “full of razor wire, barricades, and AK-47s.” She is now accustomed to rocket explosions, gunfire, and news of kidnappings and suicide bombings. “I do everything I can to stay as safe as I know how,” she says, “but I have accepted that certain things are beyond my control.”

Yet even when noting that a close friend who worked for another international outfit was murdered, with his own guard suspected of the crime, Markovich makes it clear that she has made her choice.

“I cannot hide in my room for [months],” she says. “I chose to be here.” Her work and her friends are the things that keep her going.

The country’s treatment of women has been a sobering revelation to Markovich.

“Women are neither to be seen nor heard, and they are rarely seen in public,” she says. “I have met plenty of Afghans that support women’s rights and want things to change, but these people are educated and often work for international organizations.”

Since women’s rights are not likely to advance in impoverished villages where young girls are rarely allowed to go to school, “education is a critical component to the development and future stability of Afghanistan,” Markovich says. Among the projects to which she has helped steer funding are the construction of protective walls around schools so that parents would allow their daughters to attend.

Although she had seen her share of poverty while working in Serbia, Markovich found the situation in Kabul “heartbreaking—with mothers and their children [digging] through garbage on the dusty ground, searching for food.” While many Afghans can’t support their families and have no access to electricity or clean water, let alone job training, she notes, “the grants and infrastructure projects we enable help bring these people vocational skills.” With poppy production that finances terrorism, an extreme lack of education, and a weak, corrupt central government, Afghanistan has huge obstacles to overcome. And yet, she says, “where we work, we see change, even though it’s a small portion of the population.”

—Katy Diana