During a trip to India in the summer of 2008, Milan Vaishnav C’02 witnessed something unusual. A crucial government vote was pending and the ruling coalition was determined not to fail—so they arranged to have six incarcerated Members of Parliament (MPs) released for the vote.

“I was watching it unfold on television,” recalls Vaishnav, director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Six MPs were taken from jail to vote and then six MPs went back behind bars. What was most remarkable about the moment was how unremarkable people seemed to think that was. It was on page 18 of the newspaper.”

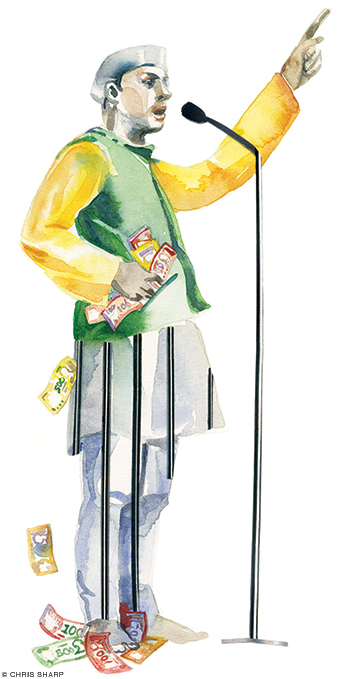

Vaishnav, then a PhD candidate in political science at Columbia University, had found his dissertation topic: the success and acceptance of suspected murderers, thieves, and extortionists in India’s government. He’s expanded on the subject in When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics (Yale University Press, 2017), which takes a deep look at the paradox of lawmakers who are also lawbreakers.

“The questions it raises are beyond India, and that’s why it’s an important book,” says Devesh Kapur, the Madan Lal Sobti Chair for the Study of Contemporary India at Penn and director of Penn’s Center for the Advanced Study of India. “It captures the deep paradox of Indian politics … Why are people voting for them? Why are political parties nominating them?”

Vaishnav wasn’t always interested in India. His parents are Indian emigrants, so the country “just didn’t seem exciting or exotic enough,” he says. “Though the truth is I didn’t know it outside of family trips and some basic Indian culture.”

His perspective changed after that fateful 2008 summer. Kapur—who had met Vaishnav in Washington a few years earlier and has since collaborated with him on a number of publications—served as his mentor and guide.

“He was the first to encourage me to make this the topic of my dissertation and then the book,” Vaishnav says. “He said, ‘This seems like it’s going to be a very hard thing to study. It’s going to require a lot of time and effort. But you’d much rather be the first person to write a book on this topic than the 13th person on some well-trodden subject.’”

Nine years, countless hours of research, and multiple trips to India later, Vaishnav had the material he needed to write this compelling, almost novel-like political-science study. In India, the world’s largest democracy, where 553 million people voted on Election Day in 2014, more than one-third of all MPs had criminal cases pending. Twenty-two percent of MPs were facing serious charges, including murder.

It’s not that voters are uninformed, Vaishnav says. In fact, “the biggest surprise was that people were voting for those people not in spite of their criminality but because of it.”

The simplest explanation is frustration with a massive, often-ineffective government bureaucracy. A civil complaint, for example, can take years if not decades to be decided. Requests for repairs to a town’s streets or for food for hungry citizens can easily be lost.

But criminal politicians have currency, as one politician told Vaishnav. They have literal cash on hand to finance election campaigns and to spend on local supporters’ needs. They’re seen as people who know how to get things done, even if they sometimes need to cross legal boundaries to do so.

“We tend to think of democracy as a good thing: It gives people choice and a certain amount of freedom,” Vaishnav says. “But it also requires having a set of functioning institutions, an able court system, welfare systems that work. Unless you invest in institutions so they can keep pace with the rising aspirations of your citizens, you open yourself up to questionable elements to fill in the breech.”

In 2010, Vaishnav asked a voter—a well-educated engineer—in the northern state of Bihara why he supported legislator Anant Singh, a self-styled mafia don-turned-politician who had been fingered in dozens of criminal cases.

“Anant Singh isn’t a murderer,” the engineer responded. “He merely manages murder.”

“The man was basically saying, ‘You may see Anant Singh as evil, but he’s a necessary evil,’” explains Vaishnav. “He’s the CEO of a protection racket, and this person [the engineer] was being protected. That’s not something unique to India. We see that in our own country and around the world.”

Singh was finally jailed without bail in 2015, ahead of state elections. Yet despite getting the boot from his political party—and without setting foot on the campaign trail—he handily won reelection.

The excruciatingly slow pace of justice is another reason so many Indian politicians have charges pending against them. Some 32 million cases—felonies, misdemeanors, and civil suits—are currently working their way through the system, and those with power and influence can make sure that justice is delayed, even denied.

“If you stall long enough, the judge dies, evidence goes missing, witnesses are scared off, investigators are transferred,” Vaishnav says. “The backlog has created all kinds of unintended consequences.”

Vaishnav never felt endangered while reporting in India. In fact, it never occurred to him that what he was doing might be dangerous.

“Remember that for these politicians, their criminal reputations are part of their attraction,” he says. “Far from wanting to hide the fact that they’re strongmen, they don’t make any bones about the fact that they are.”

—Natalie Pompilio