For the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra, Indonesia, says Dr. Peggy Reeves Sanday, harmony “is as important as power is to us.”

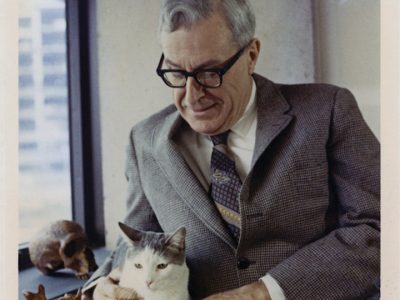

During a series of visits spanning 16 years, Sanday, professor of anthropology, observed the largest and most modern matrilineal society in the world. It was, she found, notable for its egalitarian, non-violent nature.

In “Eggi’s Village: Life Among the Minangkabau of Indonesia,” a photographic exhibition on view at the University Museum through December 7, Sanday depicts the cooperative dynamic of everyday life in one village where she developed close ties to a family of four generations of Minangkabau women.

In this society, women inherit ancestral property and have a

major voice in family matters, while male leaders discuss traditions and

settle disputes in the village meeting houses. But, Sanday notes,

“Neither male nor female rule is possible, according to Minangkabau

social philosophy, because of their belief that decision-making should

be by consensus.” One villager told her that males and females

complement each other “like the skin and nail of the fingertip.”

Sanday, who serves as consulting curator of the museum’s Asian

section, says she chose to study the Minangkabau because she wanted to

witness social interaction in a matrilineal society that was known for

its egalitarian principles in order to find out whether rape, child

abuse, and other forms of violence occurred more or less often there. In

so doing, she says, she found a society that is nearly violence-free.

Even without this distinction, however, the Minangkabau make an

engrossing study. Their name means “victorious buffalo,” and to pay

tribute to this animal, at traditional ceremonies some female

participants wear bright red headdresses pointed like buffalo horns. The

Minangkabau live in homes with upturned roofs that mimic the curves of

those horns, and — to avoid bad luck — always build them facing the

volcanic Mt. Merapi.

Through her photographs Sanday documents a colorful,

three-day-long wedding in the village that was the culmination of a

lengthy courtship between two young people and of circumspect

discussions between their families. She also depicts a ceremony held to

ward off spirits from a baby girl born on Sanday’s birthday. The infant,

born to the niece of the woman in whose home Sanday stayed, was fed

special foods, such as mashed rice and coconut water, and her lips were

touched with gold “to make her a person whose words are rich and

carefully chosen.” It was only later that Sanday learned that the

parents had decided to name the girl after her. (Now age 10, she goes by

the nickname Eggi — hence the title of this exhibition.) Such

an act was typical of the welcoming ways of the Minangkabau, Sanday

says. “They were sort of accepting a foreigner in their midst by

incorporating her name.”

In addition to having a national police system, the Minangkabau uphold their own nature-based moral philosophy known as adat. They believe that if you violate adat law,

you will be struck dead by your ancestors’ curses. “I knew one man who

died suddenly in a motorcycle accident,” Sanday says. “Nobody would dare

say it publicly, but a lot expressed privately that he had died because

of a curse that fell upon him from his ancestors from breaking adat law. He had sold ancestral property for his own gain.”

Sanday plans to return to the village this summer while she works

on a book exploring the evolution of the Minangkabau social system. But

regardless of what she’s researching in the future, she says, “I will

always go back. We’re family.”

(More information on Sanday and “Eggi’s Village” is available on her home page.