A Penn Libraries exhibit melds Arthur Tress’s surreal photography with his voracious appetite for Japanese illustration.

Arthur Tress (b. 1940) started snapping photos as a teenager scouring the decaying amusement parks of postwar Coney Island. That surreal and melancholic landscape made a lasting impression. Extensive travels in Asia and Africa fostered an interest in ethnological photography, which led to a professional assignment for the US government documenting endangered folk cultures of Appalachia. Yet Tress’s most profound journeys were into the shadowy realms of dreams, sexual desire, and “magic realism” that melded landscape depictions with staged fantasies.

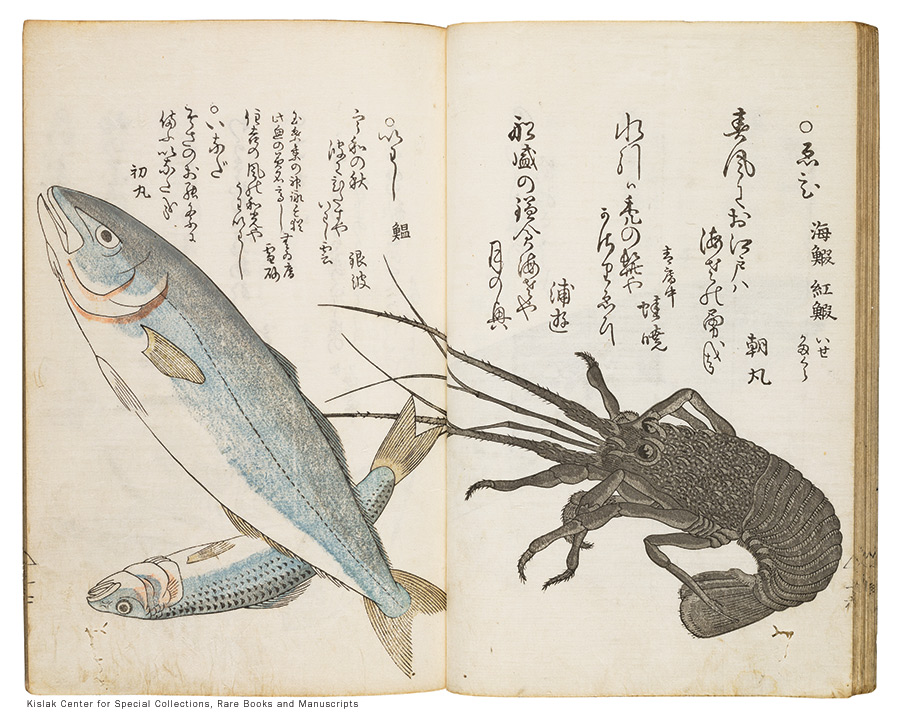

On a parallel track he also collected Japanese illustrated books. Starting with a shoestring budget during a 1965 visit to Kyoto, Tress spent more than 50 years amassing a remarkable cross-section of Japanese print culture. Ranging from 17th-century calligraphic manuscripts, to 18th-century masters like Katsushika Hokusai and Katsuma Ryusui, to popular guidebooks, kimono design manuals, and 19th-century erotica, the 1,400-title collection merges pop-cultural curiosities with rarities rivaling the holdings of the Smithsonian and Japan’s Chiba City Museum of Art, according to Julie Nelson Davis, a University professor of Modern Asian Art.

After reading Davis’s 2014 book Partners in Print: Artistic Collaboration and the Ukiyo-e Market, Tress contacted Davis and ultimately gave his collection to Penn. It formed the basis of two curatorial seminars Davis taught in 2019 and 2020, which led in turn to an exhibition cocurated by Davis and her students that opened this fall in Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, where it will be on view through December 16.

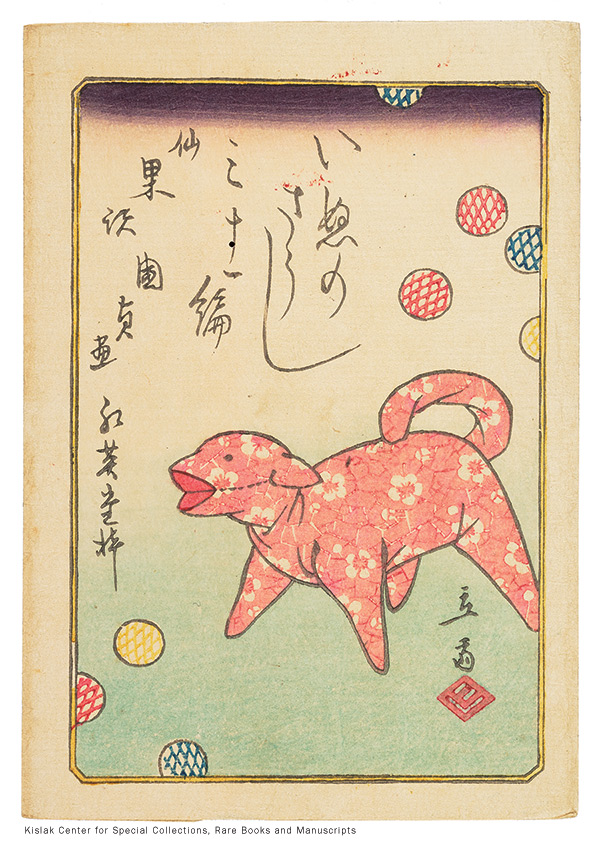

The small exhibit sparkles with surprises. The lavishly detailed landscapes of Katsushika Hokusai’s One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (1834–35) offer a familiarly idyllic depiction of the late Edo period, which found Japan’s intricate social order at peace and still largely isolated from global affairs. Barely a quarter-century later, after US Commodore Matthew Perry’s gunboat diplomacy pried the country’s ports open to foreign traders, Sadahide Utagawa would present images of American sailors approaching on vessels flagged with stars and stripes—and then staggering around in apparent drunkenness on land. Here’s a late 19th-century comics broadsheet summarizing the plot of a kabuki play. There’s an 1830 full-color rendering of how fabulously a set of bedsheets can be messed up by the missionary position. And from some year in between you’ll find a book-cover wrapper bearing a flowery pink cartoon dog that looks like a Pokémon spirit animal.

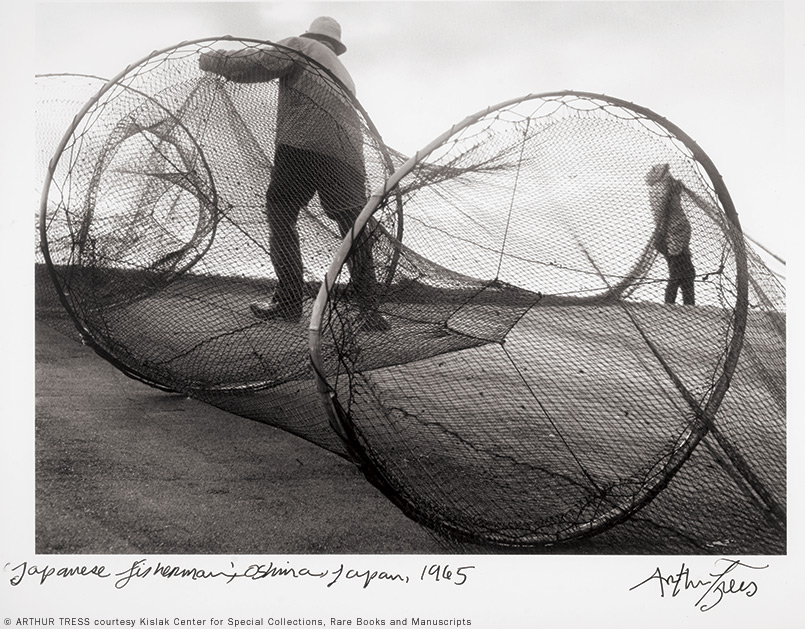

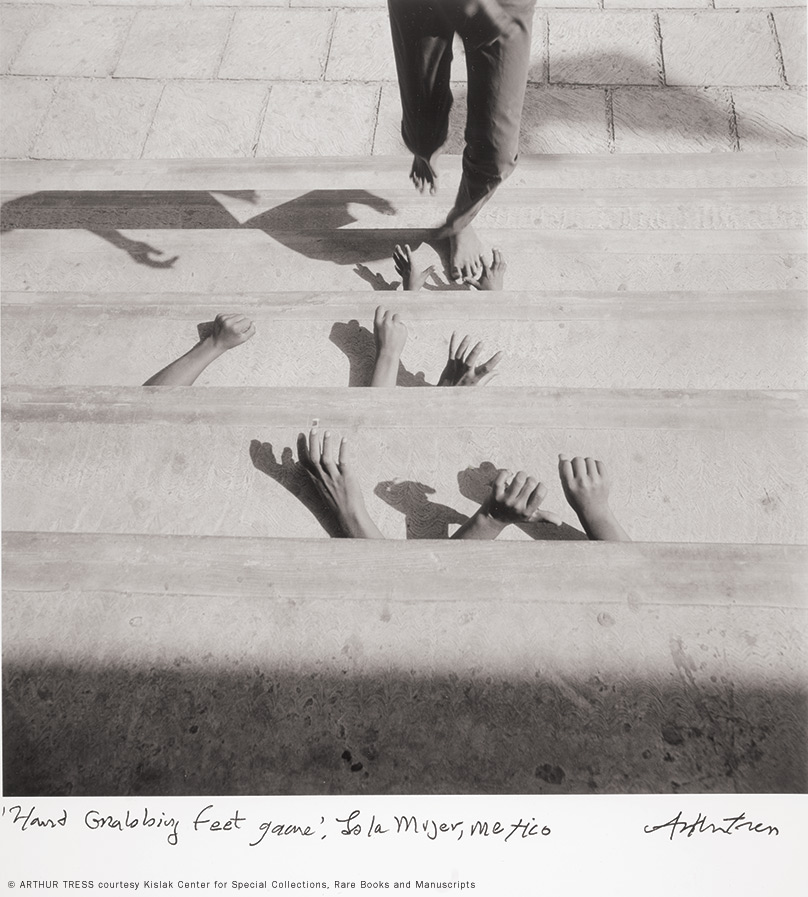

On the gallery walls surrounding these elegant and motley treasures are several dozen of Tress’s photographic prints, 2,500 of which were given to the University by Penn parents Patricia and J. Patrick Kennedy along with an anonymous donor. These too are a striking and stimulating—not to mention occasionally unsettling—set of images. Several document the photographer’s travels in Japan, as in an evocative shot of fishermen dragging giant netted traps along a shoreline. But more of them explore murkier realms: dream states where disembodied hands grasp at bare ankles ascending a flight of steps, or silhouetted children seem to fly atop a chain-link baseball backstop; and haunting compositions like “Last Portrait of My Father,” the old man’s mouth wide open and slack eyes shut as he sinks into a giant wooden armchair inexplicably stranded in a snow covered park.

“The exhibition is not biographical, exactly,” says Davis. “It’s like entering the mind of the artist.” —TP