Despite all evidence to the contrary, “the world is getting better,” argues physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis. It’s in our genes.

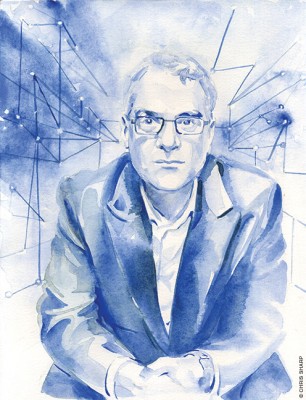

BY JULIA M. KLEIN | Illustration by Chris Sharp

When you think of shipwrecks, you might imagine the vicious adolescent dystopia of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies or the sexual depravities of the Bounty mutineers and their descendants on Pitcairn Island. Or, considering the risks of starvation, you might fret over the prospects of cannibalism. Such cases have been documented.

“Two out of the 20!” protests Nicholas A. Christakis G’92 Gr’95 GM’95, whose ambitious new book, Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society, includes a chapter on the “natural experiment” of shipwreck societies. As Christakis interprets the data, that low number of man-eating men is cheery news: it underlines the human tendency toward cooperation, even under life-threatening circumstances. Many other shipwrecks—notably the British explorer Ernest Shackleton’s famously abortive Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition of 1914-17—offer stellar examples of leadership and altruism. Stranded on desolate Elephant Island and awaiting rescue, Shackleton’s recruits relied on “friendship, cooperative effort, and an equitable distribution of material resources,” Christakis writes. When the valiant Shackleton returned with help more than four months later, all 22 of the men he’d left behind were still alive.

To Christakis, this tale of human heroism is not an outlier: the ebullient, 57-year-old Yale-based physician and sociologist sees the bright side even of disaster—and he’s developed a theory that explains why.

Published in March, and debuting on the New York Times bestseller list, Blueprint (Little, Brown Spark)is a scientific manifesto—a flag marking a territory of hope during what Christakis concedes is an era of polarization and peril. “It may therefore seem an odd time for me to advance the view that there is more that unites us than divides us and that society is basically good,” he writes. “Still, to me, these are timeless truths.”

Ranging fearlessly across disciplines, Blueprint reflects the prodigiousness of Christakis’s learning and sums up his recent research interests. But it is also a triumphant declaration of his world view, lessons garnered from a mainly fortunate life that has also been shadowed by tragedy. The book marshals a wide variety of evidence to argue not only that societies are fundamentally benign, but that their goodness has a firm genetic underpinning.

Christakis, the Sterling Professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale and director of the university’s Human Nature Lab, also suggests that genes and cultures interact and co-evolve in a variety of ways—with culture, in some cases, fostering (relatively rapid) evolutionary change. One classic example he cites is the culturally transmitted ability to control fire and cook food, which changed teeth, muscles, and the stomach, and “freed up energy to power the demanding human brain.” A more recent instance involves a group of “sea nomads,” a people called the Sama-Bajau who live in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines and spend several hours a day diving for food. As a result, Christakis writes, they have evolved “genetic mutations that appear to equip them with the ability to cope with oxygen deprivation.”

Central to Christakis’s claims is the idea of what he calls the “social suite.” Societies, he says, are universally characterized by love for partners and offspring, friendship, social networks, cooperation, in-group bias, mild hierarchy, learning and teaching, and recognition of individual identity. These traits, he maintains, are biologically ordained. In his view, culture and environment account only for variations in how these hard-wired social tendencies are expressed. In the case of partner love, for example, different cultures over the millennia have prescribed monogamy or polygyny or (in rare cases) polyandry as norms. But, for Christakis, it is the genetic blueprint that is foundational. It is our genes that “explain why culture exists at all.”

Bold and imaginative leaps—across evolutionary biology, genetics, psychology, anthropology, sociology, and other fields—are a Christakis signature. “He’s a polymath,” says Daniel Gilbert, the Edgar Pearce Professor of Psychology at Harvard and author of Stumbling on Happiness (2006). “I think that’s what impresses me most about Blueprint: It’s this sweeping synthesis … I can’t think of too many people I’ve ever met who’d be capable of producing a work with that kind of breadth and sweep.”

Christakis’s intellectual leaps have, in the past, occasioned controversy, and are likely to do so again. Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives—How Your Friends’ Friends’ Friends Affect Everything You Feel, Think, and Do (2009), coauthored with the political scientist James H. Fowler, was an immense popular success. The book and Christakis’s related academic articles drew on data from the Framingham Heart Study, a longitudinal public-health experiment, to suggest that obesity, happiness, and other traits spread through social networks in unexpected yet ultimately predictable ways. The claims spawned voluminous newspaper and magazine coverage; the research “caught the cultural zeitgeist,” Christakis says. “The attention—it was insane.” He even showed up on Time’s annual list of the 100 world’s most influential people.

At the time, a handful of economists and mathematicians groused at Christakis’s statistical methods and conclusions. He reacted by continuing to refine—and to double-down on—his social networking studies. “We thought some of the criticism was reasonable, and some was stupid, and some was unfair,” he says. “So we said in response to the critics, ‘OK, we’ll give you more and bigger experiments.’”

Some of these have been as sweeping as Christakis’s theories. In partnership with the Honduras Ministry of Health and the Inter-American Development Bank, Christakis is spearheading a multiyear field experiment involving about 30,000 people in 176 villages in rural Honduras, using software, Trellis, developed by his lab to map social networks. Begun as an inquiry into the impact of specific interventions on maternal and infant health, the project is now exploring the connections between bacterial patterns and human networks and how neighborly relationships affect the incidence of depression.

Blueprint , in asserting social universals and insisting on their genetic origins, has an even loftier feel than Connected. “He’s more than interdisciplinary—he’s almost transdisciplinary,” says Renée C. Fox, the eminent Penn medical sociologist who was Christakis’s dissertation adviser. “His work has become more and more macro. Starting with very grounded phenomena that he studied ethnographically, he keeps enlarging the framework within which he is doing research and analysis and reflection.”

“If it were not healthy for us to live in a social state, evolution would not have sustained it,” Christakis says in a freewheeling two-hour interview in his Yale office, interrupted by a talk with an undergraduate aspirant to the lab, the joyous introduction of a lab member’s six-week-old son, phone calls from two of Christakis’s three adult children, and the constant pinging of texts. “We would not live together if all we did was kill each other. Then we would have evolved to stay away. We would not live socially.”

The glittery array of academics who have endorsed Blueprint includes Penn’s Adam Grant [“Good Returns,” Jul|Aug 2013], the Saul P. Steinberg Professor of Management and Psychology at Wharton, and Angela Duckworth Gr’06 [“Character’s Content,” May|Jun 2012], the Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology and a 2013 MacArthur Foundation “genius award” recipient for her research on “grit.” Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychology professor whose 2011 volume, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, is footnoted in Blueprint, calls Christakis’s book “timely and fascinating.”

“Despite the failures of our society, the pogroms, the Inquisitions and the Crusades and the endless war, the world is getting better,” Christakis says, agreeing with Pinker. But he notes their different emphases: “Steven is arguing about the historical forces. I’m interested in forces that are prehistoric. Before colonialism, before the pogroms, before anti-Semitism, before all of that stuff, we did all these things: We loved each other, we befriended each other.

“Now, we also killed each other, we did all that stuff, too. The historical and cultural forces are overlaid over this biological foundation. And I’m completely aware that every century, every millennium is replete with horrors. But there is also good in the world. And that’s what I chose to write about.”

By coincidence, Pinker’s latest book, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018), is sparking an informal lunchtime discussion at Christakis’s Human Nature Lab. A suite of offices branching off a central conference room, the lab is adorned with social-network graphs, framed magazine covers trumpeting recent research coups, and a graphic showing Christakis’s lineal intellectual descent from such giants of sociology as Max Weber and Talcott Parsons.

Launched by an undergraduate, the conversational thread about Pinker is quickly taken up by Babak Fotouhi, an Iranian-born postdoctoral associate. Previously a postdoc at Harvard’s Program for Evolutionary Dynamics, Fotouhi holds degrees in physics, electrical engineering, and sociology, and his professional bio lists one of his interests as “the social construction of unquestioned assumptions.”

Sure enough, on this February afternoon, Fotouhi is arguing that Pinker’s very terminology—his use of the word “progress”—embodies a set of dubious assumptions. “My picture of a successful human is not wealth or health, it’s how meaningful their life is,” Fotouhi says. “We’re living in an age [in which] if you ask people the meaning of life, they get depressed, and we have opioid epidemics. If you measure in that sense, it’s not enlightenment—it’s endarkenment. It’s not progress; I think it’s de-gress. So it depends on how you measure things.”

By any measure, the Human Nature Lab, part of the Yale Institute for Network Science (which Christakis also co-directs), is a lively and idiosyncratic place. Christakis describes his work home as “an island of lost toys”: a refuge for interdisciplinary thinkers ill-suited for traditional academic departments.

“Great civilizations arise at the intersection of trade routes. And great ideas, new ideas, arise at the intersection [of disciplines],” he says. “We’ve had computational biologists, physical anthropologists, economists, political scientists, applied mathematicians, sociologists, doctors, health services researchers—we’ve had every single kind of person you can imagine come through this lab.”

Grounded in the hard sciences, Fotouhi has the skill set to apply mathematical techniques to social-science questions. Marcus Alexander, a Serbian immigrant whose title is research scientist, has pursued a similarly eccentric career arc. He earned his doctorate in government at Harvard, where Christakis was one of his two dissertation advisers. Then, at Stanford, he completed two years of medical school and a postdoctoral stint as a laboratory biologist. At the Human Nature Lab, he supervises the “wet lab,” involved in the genomic sequencing of bacteria in Honduran stool and saliva samples. Alexander hypothesizes that “the microbiome and human communities co-evolved,” and that understanding bacterial evolution over time may provide insights into human interactions and the development and structure of human social networks.

“We don’t affirmatively recruit,” Christakis says after joining lab members around a conference table. “People find us, like you guys all found us, and you have these quirky interests, and you feel like they can’t be met by existing disciplines and structuring. I see my job as lifting you up … I think the best thing I can do at any level of career is take you and guide you by the shoulders and move you to where the scientific frontier is, and say, ‘Look out from here—here’s where there’s new stuff.’ And that’s why people come to me: to get rapidly moved to the frontier.

“The other thing I used to say is, ‘We make beautiful things, whether it’s software, or methods, or data, or discoveries.’ I used to talk about how our lab was about discovery and beauty.” But Christakis’s current, somewhat secretive research gig at Apple—he’s on his first-ever sabbatical this year, splitting his time between Cupertino, California, and his mountain home in Norwich, Vermont, with only monthly visits to New Haven—has modified his thinking.

Apple, he says, talks about creating products that surprise and delight. “Surprise is a heuristic for the function being a step function, the fact that … there’s a kind of discontinuity,” Christakis says. The notion of discontinuity sounds like another way of framing those high-risk, cross-disciplinary leaps for which Christakis has been striving all along.

The range of subjects under investigation by the Human Nature Lab is matched by its diversity of techniques: computational biology, anthropological fieldwork, massive online experiments, randomized controlled field trials in the developing world, innovative data analysis, and more.

While the Honduras project, whose funders include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the NOMIS Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and India’s Tata Group, is its largest, the lab also has worked in India, Uganda, China, Tanzania, Sudan, and elsewhere. Coren Apicella, assistant professor of psychology at Penn, collaborated with Christakis and others on fieldwork involving the Hadza, a group of hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. The team investigated friendship, cooperation, and social networks—research that is featured in Blueprint. “We found that the structures of the networks were the same as among Americans living in a modernized society,” Christakis says.

The Human Nature Lab meeting runs rapidly through a range of current projects, which include building hybrid systems of humans and robots that interact socially, studying risk behaviors in marginalized communities, and exploring whether people with different social tendencies emit different scents.

Christakis says he believes that mosquitoes “should fly toward social people because there will be a cluster of them, so if you miss the first person, then you might find someone else to eat.” He was so obsessed with the mosquito experiment at one point that his Yale colleagues festooned the lab with mosquito stickers.

One of his sociology graduate students, Jacob Derechin, with a background in physics and an interest in biology, still likes the mosquito idea because “the mosquitoes are cool, and also not that expensive—I find, wholesale, you can buy thousands of mosquitoes for, like, a hundred bucks.”

Christakis has nevertheless decided to dispense with the insects and go a different route to investigate his differential-scent hypothesis. But he reassures lab members: “If you come to me with a crazy idea, I very rarely say no.”

According to his younger brother, Dimitri A. Christakis M’92, even Christakis’s adolescent play was creative. “He was a legendary pillow fighter, the best in the entire neighborhood, undefeated,” says Dimitri, a pediatrician who directs the Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development at the Seattle Children’s Research Institute. “He invented many techniques, including taking a small pillow and compacting it so that it swung at the end of the case like a mace. It was that pillow that made a dent in our plaster wall when I ducked under it. We later moved a painting over it to cover [the dent]. My mother asked why we hung it so low.”

Dimitri, who followed his brother through the elite St. Albans School in Washington, DC, and then Yale, recalls Nicholas as “an extraordinary student” who set an intimidatingly high academic bar. They have three other siblings: a younger biological sister, an adopted sister who is African American, and an adopted brother of Taiwanese descent, who is now a renowned endocrine surgeon. Christakis’s mother, Lenna (she added the second n late in life, Christakis says, to combat mispronunciation), had a staunch commitment to social justice that included welcoming relative strangers to their Thanksgiving table. “We were proud of our mother,” Christakis says, choking up at the memories. “She had grace.”

Both parents came to the United States from Greece as Fulbright Scholars. Christakis’s mother matriculated at Vassar; his father, Alexander, at Princeton. They met through friends, married, and attended graduate school at Yale, where his father trained as a nuclear physicist and his mother as a physical chemist, a rare choice for a woman of that era.

When Nicholas was three, the family returned on vacation to Greece, where his father was unexpectedly drafted into the military. But they were able to relocate to Washington about three years later, after Alexander Christakis took an urban planning job with a Greek architectural firm.

In 1968, when Nicholas was six,his mother was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, a type of blood cancer. He spent the remainder of his childhood in the shadow of her illness. During a seven-year remission, she taught high school mathematics, adopted a teenage boy and a young girl, and earned a doctorate in clinical psychology from Howard University. But, in the mid-1970s, the cancer returned, and Nicholas’s father left. (He remarried and now lives in Crete.) It was no coincidence that all three of Lenna’s sons became doctors—or that Nicholas’s medical interests would include prognosis and end-of-life care.

In the midst of earning his MD and master of public health degree from Harvard, Christakis took time off to care for his mother. “‘It’s time for you kids to go back to school, and it’s time for me to die,’” Christakis recalls her saying. “She was like a Samurai.” The end came when she was 47, and he was just 25, a huge emotional blow.

Deciding against becoming a plastic surgeon, Christakis set his sights on an academic career. An essay by Fox, “Training for ‘Detached Concern’ in Medical Students,” affected him deeply, and he arranged a meeting with her in Philadelphia at a café near her Rittenhouse Square home.

“She was incredible,” Christakis recalls. “She got me a piece of chocolate cake, and I love chocolate cake! She was so smart and so kind as well, and, of course, my mother had just died, so I’m sure there was some transference going on as well.”

Fox, professor emerita of sociology and Annenberg Professor Emerita of the Social Sciences, also remembers that first encounter. Christakis, she says, was “an extraordinarily brilliant young man with a tremendous amount of life energy and imagination, and also a deep and empathetic relationship to some of the issues of the human condition.” She would become both his academic mentor and a close family friend.

Shortly before that, Christakis had met his future wife, Erika L. Christakis (née Zuckerman) ASC’93, an early-childhood educator and writer. It was “love at first sight,” they both say.

“Our origin myth is a nice one,” he says. Their meeting was, in fact, a network phenomenon. Christakis’s high school best friend’s girlfriend had become a friend of Erika’s. After Erika’s 1986 graduation from Harvard, they were in Bangladesh together, working with a women’s health development program. At one point, the friend told Erika: “I just thought of the man you’re going to marry.” As Christakis relates it, Erika’s response was: “We need a guy who’s closer to here, not 10,000 miles back in the United States.”

Fast forward six months to Washington and an arranged meeting at the friend’s family home. Christakis’s first glimpse of Erika was of her arguing. “She was just full of life,” he says. “I was attracted to Nicholas’s warmth and charisma and intelligence,” Erika says.

But the relationship almost faltered before it began. Intending to show that he was “good husband material,” Christakis followed the two children of the household to a bedroom to admire their possessions, which included a prized cobra skin. “The thing you need to know about Erika is that she has a psychological phobia of snakes. I did not know this at the time,” he says. “Erika, who is at the door, blurts out: ‘If you touch that snakeskin, you’ll never touch me.’ And my heart soared because she blurted out that she liked me—she was disinhibited by her fear of the snake.” They had their first date three days later.

Christakis moved to Philadelphia in 1989, and Erika joined him in the city a year later after obtaining a master of public health degree from Johns Hopkins. While Erika was pursuing a master’s degree at Annenberg and giving birth to their first two children, Christakis completed a medical residency, did postdoctoral work as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, and earned his sociology doctorate.

Their next stop, in 1995, was the University of Chicago. Living in Hyde Park, Christakis met Barack Obama once (they alsoshared a babysitter) and got to know Arthur H. Rubenstein, his department chair at the timeand, from 2001–11, executive vice president of Penn’s health system and dean of the Perelman School of Medicine.

“He is so innovative and entrepreneurial and creative,” says Rubenstein, who adds that he tried unsuccessfully to recruit Christakis to Penn shortly before the sociologist moved to Yale. “Nicholas is able to combine creative ideas and thoughts, and then do the experimental work—with rigorous science and biostatistics and epidemiology—to really prove what he thinks about. And that’s kind of a unique combination.”

Christakis’s research at Chicagofocused on “prognostication and ICU decision making and hospice delivery systems,” and his clinical practice involved hospice visits to the city’s predominantly African American South Side. In 1999, the University of Chicago Press published his first book, based on his Penn dissertation, Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care.

“My wife was very worried that I was getting very depressed because, literally, I was surrounded in clinical work by people who were dying,” Christakis says. So he made a deliberate, if modest, turn toward “studying the widowhood effect and the health benefits of marriage.” That move, he says, “sets the stage for my interest in social networks because then I start thinking about pairs of people and how one person affects another.”

In 2001, Christakis was recruited to Harvard, to professorships in both sociology and medicine. There, he says, he became interested in the evolutionary biology of human social interactions and its implications for culture, behavior change and public health—laying the foundation for both Connected and Blueprint. From 2009–2013, he and Erika served as co-masters (the title has since changed to faculty dean) of Pforzheimer House, one of Harvard’s 12 residential houses.

Daniel Gilbert says they became fast friends on Christakis’s initiative “because A) he reads everything, and B) he’s this big, warm, friendly, loud Greek guy who wants to know everybody.” Gilbert had recently publishedStumbling on Happiness, on how people think about the future. “And Nicholas said, ‘I’m your colleague in sociology downstairs, I wrote a book about prognosis, on how patients think about the future, and I wonder if we have some interests in common.’”

It turned out that both had largely moved on from the subject of prognostication. “I’m not sure we ever had another conversation about that topic,” Gilbert says. “But what we did find out is that we liked each other and had a lot of fun talking about ideas together.”

When Christakis decamped for Yale in 2013, Gilbert says, “I think, for Harvard, it was a great loss. For me, personally, it bordered on a tragedy to not have him nearby.” But he understands why his friend made the choice he did. At Harvard, Christakis was “a citizen of two worlds,” sociology and medicine, while at Yale, he says, “they gave him this remarkable institute, which he runs, which is really a great intellectual home for him.”

Two of Christakis’s three children, a son and a daughter, have attended Yale (his other son graduated from Harvard). A charismatic lecturer, Christakis taught his popular medical sociology course, which attracted upwards of 200 students, as well as graduate seminars. His wife held a lectureship at the Yale Child Study Center. And in 2015, he became master (now “head”) of Silliman College, one of Yale’s residential colleges, while Erika was appointed associate master.

Just two months into their Silliman tenure, they found themselves painfully embroiled in the ongoing debate about free speech and racial sensitivities on college campuses. The incident was sparked by an email from Erika in response to administrative guidelines on the selection of (inoffensive) Halloween costumes. Speaking from a child-development perspective, she suggested that students were mature enough to dress themselves without adult interference. And she quoted what she said was Nicholas’s advice: “[If] you don’t like a costume someone is wearing, look away, or tell them you are offended. Talk to each other. Free speech and the ability to tolerate offence are the hallmarks of a free and open society.”

Impassioned student protests, charging the couple with racism and calling for their ouster, erupted. A viral video showed Christakis telling a group of students in the Silliman courtyard, “I have a vision of us … as human beings that actually privileges our common humanity,” and being met with insults and curses. In the fallout, Erika left her teaching job, while Nicholas announced his sabbatical. And, at the end of the academic year, the couple resigned their Silliman posts. In an Op-Ed in the Washington Post a year after the incident, Erika suggested that their ordeal exemplified a “worrying trend of self-censorship on campuses.”

The Halloween costume controversy is not exactly Christakis’s favorite topic. In a New York Times opinion column in March, Frank Bruni quoted him as calling it one of “the top 10 worst things to happen in my life,” but adding “there are other competitors for that honor.”

Blueprint begins with a 1974 scene of mob protest in Athens, in which Greeks frustrated by dictatorship screamed, “Out with the Americans!” Christakis, a frightened boy at the time, writes: “Perhaps oddly for a man who has spent his adult life studying social phenomena, I have never liked crowds.”

Reading that, he says during the office interview,“You’ll get a sense of my thoughts on how mobs can lead people astray.” The reasons he stepped down from Silliman “are very complex and not something I talk about,” he says. “Suffice it to say that those experiences had effects on my whole extended family. And I was and am on the side of young people.” (With their three biological children grown, the Christakises are now caring for a foster child.)

“I think the same qualities that can lead to a lot of goodness in the way we live together can also lead to a lot of badness,” he says. “And my book is an effort to explain why, nevertheless, despite the ways we’re led astray, on the whole we make good societies.”

In fact, he says, “it’s an extended argument about sociodicy—a vindication of society, despite its failures. It must be the case, across evolutionary time, that the benefits of a connected life outweigh the costs. I’m interested in how natural selection has shaped not just the structure and function of our bodies, not just the structure and function of our minds, but the structure and function of our societies.”

Social systems themselves, he notes, have selective effects. “Those among us who can survive in the new order that we create then get selected for, and so then we get more and more of them,” he says. “Cooperative people fare better in cooperative environments. A cooperative person is killed in a non-cooperative environment.”

What’s more, he says, “The social environment we take with us wherever we go—that’s the other amazing thing about it. So unlike the physical environment, which varies from place to place, the social environment is the same: People have friends everywhere, people teach other people everywhere, people love their partners everywhere.”

The conclusions of Blueprint are“extraordinarily positive” and “very uplifting,” says Fox, who still talks to Christakis regularly. “That is his almost metaphysical world view, but that that’s where he came out is not to be taken for granted, since he’s extremely knowledgeable also about the darker sides of the human condition and suffering.”

Fox, a polio survivor, tells one final story about Christakis and their “very special teacher-student relationship.” This story, too, takes place in Athens, where she was on a research trip, and Nicholas happened to be visiting. “He helped me to climb to the top of the Acropolis,” she recalls. “I was less physically handicapped then than I am now, I was younger, but I still could not have done it alone.” Analogizing the experience to “the vast vista of his work,” she says: “By helping me up that path, he made it possible for me to see this great panorama that I wouldn’t have been able to see otherwise.”

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, last profiled Eva Moskowitz C’86 for the Gazette. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.