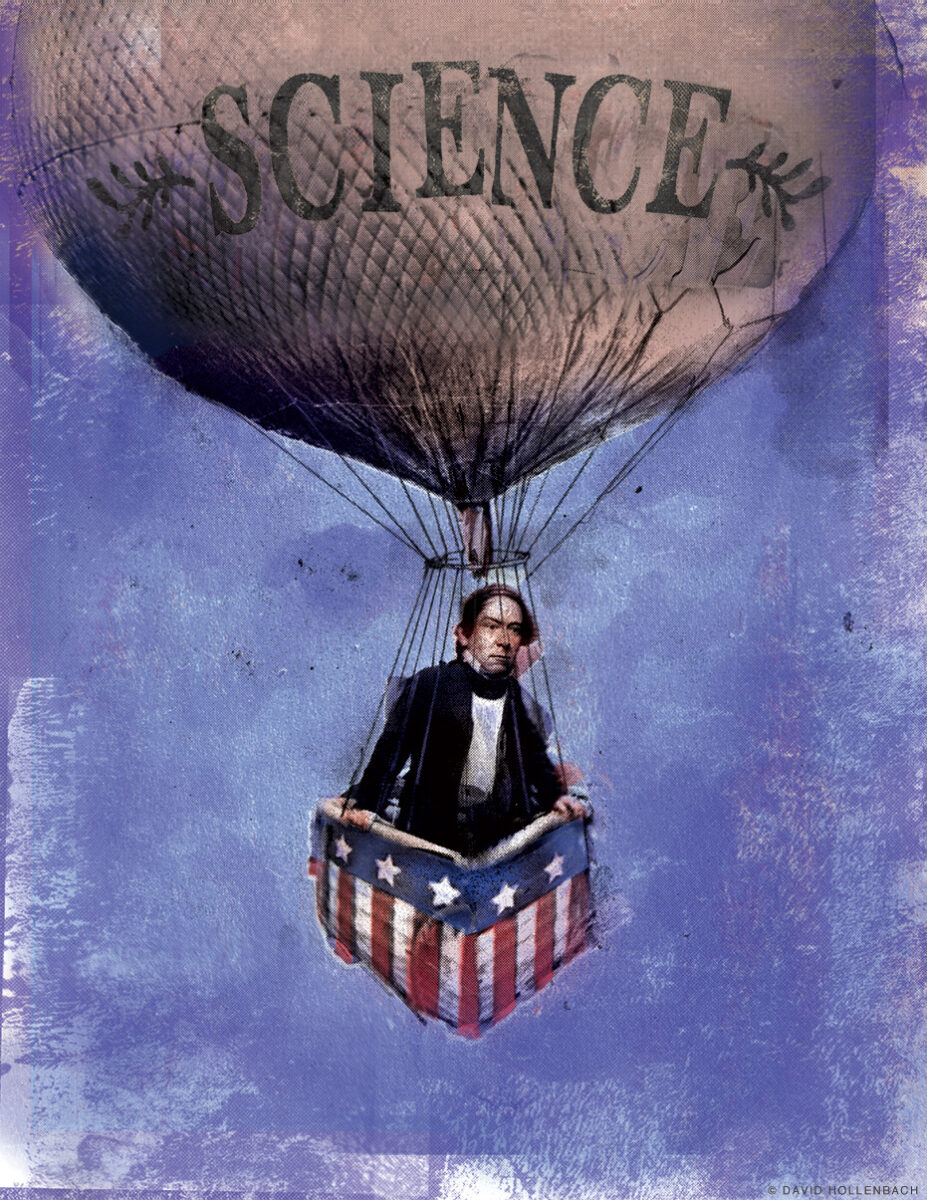

The great-grandson of a famous founder (of the nation and this University) and “boyhood’s friend” of the president of the Confederacy, educational reformer and onetime Penn professor Alexander Dallas Bache made his own reputation by championing the professionalization of American science in the mid-1800s.

By Dennis Drabelle | Illustration by David Hollenbach

“Hang Jeff Davis on a sour apple tree” goes the first line of “The Field Cry of Penn,” now mostly banished (for a vulgar refrain, among other things) but once regularly sung at Franklin Field—and still familiar to many alumni. The tune was recognizable as that of Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” itself borrowed from the existing song “John Brown’s Body,” which in turn was set to the melody of “Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us?,” a Methodist hymn attributed to William Steffey, who may have cribbed from a folksong.

Aside from this impressive history of pilferage and its on-again, off-again presence in the Penn Band’s repertoire, the song is worth remembering because it figures in a historical irony. One of Jefferson Davis’s best friends was a fellow West Point graduate who taught at Penn and later became what the historian William H. Goetzmann called “the most powerful force for professional pure science in America.” The force’s name was Alexander Dallas Bache, and he happened to be a great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin.

Sarah Franklin, the daughter of Franklin and his wife, Deborah, married Richard Bache, an underwriter of ships and cargoes. In 1805, one of the couple’s sons, also named Richard, married Sophia Dallas, daughter of Alexander J. Dallas, who served as President James Madison’s secretary of the treasury; in that capacity, Alexander Dallas supervised an agency called the Coast Survey, which his grandson and namesake was to transform into an incubator of scientists. Sophia’s brother, George M. Dallas, became vice president under James K. Polk, and altogether the Baches could hold their own with the Franklins when it came to political influence and social standing.

It’s noteworthy, then, that Dallas Bache, as the second Alexander was called, had little use for what Penn sociologist E. Digby Baltzell W’39 Hon’89 labeled Proper Philadelphia in his study Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia. The sticking point for Bache was what he called the prevailing “negative attitude toward academics and intellectuals in general,” as evinced by the Penn trustees’ opposition to establishing a graduate school in the 1850s. In a letter to a friend, Bache distanced himself from “the old Philad. stamp.”

Born in Philadelphia in 1806, Dallas was the first of Richard and Sophia’s nine children. Before there could be a 10th, Richard fled to Texas, probably to get away from his creditors, leaving Dallas to help his mother raise the rest of the brood. With her encouragement, the boy accepted an appointment to the US Military Academy in West Point, New York, at age 15. Though almost certainly the youngest cadet in his class, he graduated as its top student four years later—without getting a single demerit. Yet his own assessment of his intellect was guarded: “I knew that I had nothing like genius, but I thought I was capable by hard study of accomplishing something.” As explained by Bache’s biographer Merle M. Odgers C1922 G’24 Gr’28, the boy employed a trick to keep his mind on his work: studying while seated on an unstable chair. Should he lose his concentration, a wobble from the chair would recall him to duty.

After graduation, Bache stayed on to teach at West Point for a year, then transferred to the prestigious US Army Corps of Engineers. While working on the construction of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, he met Nancy Clarke Fowler, whom he wed a few years later while on leave from the Army and teaching natural philosophy and chemistry at Penn. Bache was only 22 years old, but that didn’t stop him from also being appointed secretary of the University.

Bache resigned his commission and taught at Penn for seven years, demonstrating a remarkable ability to control his classes during a period of marked undergraduate rowdiness. The punishment meted out to one poor fellow—expulsion for making a “shrill noise in Chapel”—shows how determined to impose order the University was. An admiring colleague thought he knew how Bache managed to keep his classroom shrill-free: “Even his successors had trouble with his students, so it can hardly have been the fascinations of the subjects of physics, chemistry, and geology that kept the students orderly. It would seem to be possible to make teaching so interesting that students will not want to misbehave.”

Despite teaching three classes a day five days a week, conducting research, and performing his secretarial duties, Bache found time to become a stalwart of the American Philosophical Society, the Franklin Institute, and the Wistar Club—and to dabble in educational reform. Bache’s espousal of that cause appealed to the trustees of Girard College, an embryonic private grammar and high school, and they lured him away to become its president in the fall of 1836.

Established by the will of Stephen Girard, a French immigrant who made a fortune as a merchant and banker, Girard College was still in the planning stages when Bache took the helm. In the interim, its trustees sent him off to Europe on a mission to learn all he could about modern education.

In his monograph Patronage, Practice, and the Culture of American Science: Alexander Dallas Bache and the U.S. Coast Survey, historian Hugh Richard Slotten brings up what could have been a touchy issue for Bache both in Europe and at home: the inevitable comparisons of him to his world-famous great-grandfather. In fact, however, Bache didn’t seem to mind greetings like the one he got from an elderly German educator: “Mein Gott, now let me die, since I have lived to see with mine own eyes an emanation of the great Franklin!” The Franklin emanation even tackled problems once addressed by his ancestor, such as the movement of storms along coastlines.

Thanks to Bache’s strong work ethic, his European trip was far from a junket. In two years abroad, he visited an estimated 278 schools in a dozen or so countries, along with numerous institutes of science. His industriousness culminated in a 666-page report that Odgers rates “a masterpiece of educational research and compilation.” On returning to Philadelphia, however, Bache found that Girard College had yet to open its doors—indeed, they were to remain unopened for another decade. Though still nominal president of Girard, Bache served as superintendent of Philadelphia’s Central High School from from 1839 to 1842, helping to draw up a curriculum strong in the sciences.

While at Central, Bache had to deal with a prankster who reduced everybody to tears by sprinkling red pepper into the heating system. Within an hour, Bache knew the culprit’s identity but kept in mind that this was his first offense. “He took the boy aside,” Odgers writes, “talked to him in a fatherly manner, urged him to straighten himself out and not ‘blast his life,’ and then let him go.”

Bache left Central High School and Girard College to rejoin the Penn faculty in 1842. The director of the Coast Survey died a year later, and Bache was appointed his successor. At age 37, he had found his calling.

Bache took over the agency with two goals uppermost in mind: to increase funding and thereby accelerate the pace of mapping the nation’s coastlines; and to improve the standing of American science.

He shared the latter goal with a fellow scientist named Joseph Henry, soon to be the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The two reformers had met in 1833, when Bache was teaching at Penn and Henry at Princeton. They renewed their friendship when Bache’s information-gathering residence in Europe overlapped with a vacation taken by Henry. Together, they obtained audiences with such scientific grandees as Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Friedrich Gauss. On his return to the States, Henry wrote to Bache, “I am now more than ever of your opinion that the real working men of science in this country should make common cause and endeavor by every proper means unitedly to raise our scientific character, to make science more respected at home, to increase the facilities of scientific investigators and the inducements to scientific labors.”

We can put this sentiment in context by citing a critique made by the English wit Sydney Smith 13 years earlier in the Edinburgh Review: “In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book? or goes to an American play? or looks at an American picture or statue? What does the world yet owe to American physicians or surgeons? What new substances have their chemists discovered? or what old ones have they analyzed?”—and so on through several more barbed questions. The Bache–Henry project, in other words, was part of an American urge to catch up with Old World culture and learning. (For the record, within a few years of Smith’s diatribe lots of people in the four corners of the globe were reading books by Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper.)

The two young scientists also had a specific malady in mind: charlatanism. In an 1838 letter to Bache, Henry said that since his return from Europe he had “often thought of the remark you were in the habit of making that we must put down quackery or quackery will put down science.” As examples of the crackpots who gave American science a bad name, Slotten cites the polymath Constantine Rafinesque, who maintained that Black indigenous people were living in North America before the first Europeans reached its shores; and the physician Henry Hall Sherwood, whose views on terrestrial magnetism Henry scorned as “perfectly puerile and entirely unworthy.”

Almost as bad was Matthew Fontaine Maury, superintendent of the US Naval Observatory and author of The Physical Geography of the Sea (1855), which Bache cited as containing “more absurd propositions than are to be found in any book ever published by a person in such a high position.” It didn’t help Maury’s cause that Bache saw him as encroaching on the Coast Survey’s work. Along with Henry at the Smithsonian and Louis Agassiz and Benjamin Peirce at Harvard, Bache made the newly formed American Association for the Advancement of Science a vehicle for undermining Maury’s influence.

At times Bache’s campaign to elevate American science smacked of elitism—he envisioned the ideal practitioner as belonging to “an aristocracy in the form of an elite of wealth and family influence.” Yet Joseph Henry had risen from a humble background, so professional mobility was not foreclosed. He and Bache can also be accused of provincialism for touting Philadelphia science as the model to be emulated and dismissing New York as home to, as Henry put it, “all the Quacks and Jimcrackers of the land.” In any event, Bache saw to it that his agency elevated American science by patronizing—in the sense of “doing business with”—it. One of his methods was to commission papers from his own employees and outside consultants, and to hold the submissions to high standards. Bache did this hundreds of times during his tenure at the Survey, and 42 of his authors eventually made it into the Biographical Dictionary of American Science.

Bache also drew upon his political savvy. In his second year of directing the Coast Survey, he raised the number of states in which it operated from nine to 16. He also made two other politically astute moves: scrapping his predecessor’s policy of using New York as the base from which surveys proceeded north and south in favor of having multiple points of departure; and winning support from the Massachusetts congressional delegation by making the survey of Boston Harbor a high priority. “Before the close of the forties,” Odgers reports, “scientific work was being carried on in every state on the Atlantic seaboard and on the Gulf of Mexico, and parties with their instruments had begun to conquer geodetically the coast of the Pacific.”

For all of Bache’s canniness, however, his agency ran into opposition from legislators representing landlocked states. “For many years,” a friend of Bache’s observed, “there was scarcely a session of Congress, without some vehement attack upon the Survey in each House, made for the purpose of defeating the appropriations.” In his defense, Bache could cite an American Association for the Advancement of Science report claiming that the Survey was saving the nation $3 million a year in prevented shipwrecks.

He could also rely on support from a powerful crony: Jefferson Davis, secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce and later a US senator from Mississippi. The two former cadets took a road trip to New England in 1853, visiting Boston, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and the Coast Survey camp at Blue Mountain, Maine. Five years later, Senator Davis returned to Maine with his wife, Varina, to stay with Bache at another Survey camp, on Humpback Mountain.

In her Jefferson Davis Ex-President of the Confederate States of America: A Memoir by His Wife (1890), Varina shows her husband risking his health for Bache the following year. While recuperating from a long illness, one day “Mr. Davis was taken in a closed carriage to address the Senate on an appropriation for the coast survey.” Varina had tried to talk Jefferson out of going, but he had replied, “‘It is for the good of the country and for my boyhood’s friend, Dallas Bache, and I must go if it kills me.’ He … carried his point, then came almost fainting home.”

Bache’s own health suffered from his tendency to work too hard, and he enjoyed getting away from the office and roughing it with his survey crews. “We have been half roasted in our tents within the last week, after actually suffering with cold a week before,” he wrote in a letter from 1848. “Such is canvas life.” Speaking of canvas, one of Bache’s employees for a time was the future painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who found his work as a Survey draftsman boring and sometimes played hooky. Whistler learned how to etch during his stint with the Survey, a skill he used to good effect as an artist.

Bache and his wife had no biological children but adopted his nephew Henry Wood Bache after the boy’s father, George Meade Bache, a naval officer on temporary duty with the Survey, died in a shipwreck. Thus, fatherhood joined Alexander’s lengthening list of responsibilities, which also included being a Smithsonian regent, president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a member of numerous American and European scientific societies. In December of 1858, he took time out to write a letter of recommendation for a Penn alumnus, Isaac Hayes M1853, who was drumming up support for an expedition to discover the reputed open polar sea [“Pointing the Way to the Pole,” Nov|Dec 2011].

In 1863, still leading the Survey, Bache oversaw the construction of fortifications for the defense of Philadelphia during the Civil War. A colleague remembered him working 18-hour days, with the result that “his health gave way and he was sent to Europe.” Two years later, Bache was in such bad shape that the same colleague had to cross the Atlantic and bring him and his wife home. After Bache died in Newport on February 17, 1867, Joseph Henry eulogized him as “a martyr to the cause of his country in the hour of its peril.”

Earnest and self-disciplined as he was, Bache could also be a boon companion. He enjoyed serving and drinking wine—a taste Varina Davis attributed to the time he spent with Humboldt, who kept a fine cellar. In her book, she recalls hosting a bibulous Christmas party at which the Baches were guests.

“Mr. Davis … was persuaded to sing an Indian song, and Dallas Bache put on a fur coat to personate Santa Claus, and gave [out] the presents in the most truly dreadful doggerel. Six months afterward, one warm summer day, Mr. Davis exclaimed that he felt oppressed; ‘but,’ said he, ‘I think it is not the weather, it must be the memory of my Indian song last Christmas, and dear Dallas Bache’s execrable doggerel. I am sorry I did not make him sing, and do the rhyme myself.’ As the Professor could not turn a tune, and Mr. Davis had no capacity for jocular rhyme, I thought they had reached their utmost limits as it was, but refrained from venturing an opinion.”

We lack direct evidence of the Civil War’s effect on the Bache–Davis friendship, but the glow that suffuses Varina Davis’s Memoir almost every time she mentions the Baches is telling. Also relevant is a January 20, 1861, letter from Jefferson Davis to his old boss Franklin Pierce. Under the salutation “Dear Friend,” the incoming president of the Confederacy explains to the former president of the United States that “Civil war has only horror for me, but whatever circumstances demand shall be met as a duty and I trust be so discharged that you will not be ashamed of our former connection or cease to be my friend.” (Pierce fulfilled Davis’s “trust” by paying him a visit after the war, when Davis was incarcerated in Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia.)

If, as seems likely, Davis wrote a similar letter to Bache, it must have been galling for the recipient to learn that his “boyhood’s friend” was doing his utmost to destroy the Union that Bache’s great-grandfather had worked so hard to establish. Yet it’s hard to imagine the compassionate Alexander Dallas Bache deciding to cancel the friendship, let alone go looking for the nearest sour apple tree.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Power of Scenery: Frederick Law Olmsted and the Origin of National Parks.