Arthur Drooker’s infrared photographs of historic ruins in the U.S. conjure a “spirit world of haunted beauty.”

By John Prendergast

Photographs by

Arthur Drooker C’76

Merrell Publishers Limited, 2007. $45.00

(www.americanruinsbook.com)

On the cover: Rhyolite, Nevada (1904). A gold discovery in 1904 brought more than 10,000 people to Rhyolite by 1907, but a financial panic that year initiated a decline that by 1919 had turned it into a ghost town presided over by its tallest building, the John S. Cook Bank.

The sites included in American Ruins, a collection of 100 compelling images by Los Angeles-based photographer Arthur Drooker C’76, range from upstate New York to Oahu, Hawaii, but the idea for the book originated far from the U.S.—in Cambodia, to be exact.

“In 2003 I satisfied a longtime curiosity to visit the temple ruins at Angkor, and I was just blown away by the architecture and the whole environment there. It really was quite mesmerizing,” Drooker recalls. “It started me thinking, ‘God, I wonder what ruins there are in this country?’”

Drawing on the Internet and other research sources, plus his own knowledge of ruins in the Southwest, Drooker soon “came up with a pretty good sized list of sites,” which he then narrowed down to 25 locations based on three criteria: All the sites had to be preserved as ruins by a public or private entity, they had to have historic value, and finally “they had to look good in infrared,” he says.

While “the infrared band of light on the spectrum is invisible to the human eye,” Drooker notes in the book’s introduction, “a specially adapted digital camera can record it. What it sees is a spirit world of haunted beauty.” The technique turns grass and tree-leaves white, makes clouds “really pop from the sky,” and causes shadows to seem to hover, “almost take on a certain dimensionality,” he says. The result is a “ghostly look that I find very evocative and [that] brings out the visual poetry” of the ruins featured in the book.

“It’s almost like casting,” he adds. “To get the real wonderful effect of it the subject matter should be situated well in nature—urban ruins wouldn’t look as good.”

Drooker, who majored in American Civilization at Penn and has worked in documentary filmmaking as well as photography, first started experimenting with infrared back in the mid-1990s. At the time, he had to use infrared film, which required a special camera-filter and was so sensitive to light that it had to be loaded and unloaded in complete darkness. On location, that involved a black bag with two armholes and “lots of fumbling,” he recalls. These days, he uses a 35-mm digital camera converted to shoot only infrared. The difference is “like night and day and much preferred,” he says with a laugh.

In his choice of sites, Drooker aimed to be “eclectic rather than encyclopedic.” The finalists include some familiar landmarks—Harper’s Ferry, the Alamo, Alcatraz—as well as others that are much less well known. Among Drooker’s own favorites is Bannerman Castle, built in the early 1900s as a warehouse for military surplus. “It’s like an old Scottish castle plunked down in the middle of the Hudson River about an hour north of New York City,” he says.

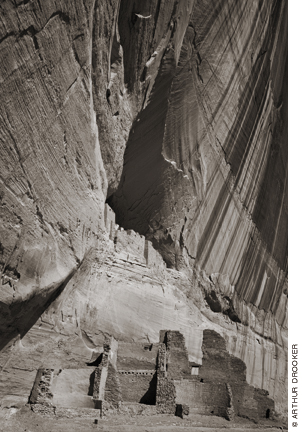

Another standout, the White House Ruin, a part of the Anasazi Ruins in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, that dates from the 1200s, had special meaning for Drooker. It had previously been photographed by Timothy O’Sullivan, “who made his reputation as a great Civil War photographer but later joined a lot of the military expeditions out West,” he says. “I’ve always loved his work.” (A stereoscopic image made by O’Sullivan in 1873—perhaps the first photo taken of the site, Drooker says—is reproduced early in the book.) Famed nature photographer Ansel Adams also photographed the area much later, and, while his own work is different from his predecessors, Drooker sees himself as continuing in a tradition.

Having been inspired by a non-U.S. site to compose American Ruins, Drooker is now returning the favor with his follow-up project—a likely multi-year effort to photograph ruins around the world, with an eye toward “architectural diversity as well as some surprises,” he says. For example, while he won’t be shooting the Parthenon “because everyone has seen it,” he hopes to get to Sicily, “where there are some great Greek temples.”

His first stop, though, in February, will be Australia, where he will photograph the “wonderful, notorious prison ruin” at Port Arthur in Tasmania, which functioned more or less as the penal colony’s Alcatraz, housing the most dangerous and incorrigible inmates, and today is among the most visited historic sites in the country, he says.

In a brief foreword, historian Douglas Brinkley links Drooker’s work of celebration and preservation with the passage of the Antiquities Act of 1906 under President Theodore Roosevelt, and with the present devastation in New Orleans, where “new ruins spring up like mushrooms.” To the depressing thought that, in a world of global warming and chemical and nuclear threats, “everyplace might someday become a candidate for Drooker’s ruins portfolio,” the images themselves offer a kind of antidote, he concludes.

“The spirit harbored in these photographs, to my mind, is that, in the end, nature wins. That is comforting,” Brinkley writes. “For that reason alone, I find Drooker’s vision as soothing as the cool repetition of ocean waves. His art is a gift to Old Time America.” —J.P.