For Demetrius Oliver, transcendent art is all in the stars.

By Lesley Valdes | Crawling on all fours through a human-sized dog door for art is not for everyone. But it’s the only way to view the dog-star Sirius, centerpiece of Canicular, the playfully serious exhibition by Demetrius Oliver GFA’04 at the Print Center of Philadelphia.

Just getting into the Canicular “observatory” is a feat. The exhibition has been dogged by obstructed firmaments since its January opening, and by the end of that month it had only been open nine times—though it still drew some 400 visitors. But when you do enter the faux observatory on the gallery’s second floor, there, courtesy of a live feed, is Sirius, brightest star in the Northern Hemisphere (with 26 times the wattage of our sun), looking like an outstretched, twitching, ghostly hand. And for those who might wonder why anyone would go to such trouble to view a star, Oliver has a characteristically pithy response: “It’s experiential.”

Just getting into the Canicular “observatory” is a feat. The exhibition has been dogged by obstructed firmaments since its January opening, and by the end of that month it had only been open nine times—though it still drew some 400 visitors. But when you do enter the faux observatory on the gallery’s second floor, there, courtesy of a live feed, is Sirius, brightest star in the Northern Hemisphere (with 26 times the wattage of our sun), looking like an outstretched, twitching, ghostly hand. And for those who might wonder why anyone would go to such trouble to view a star, Oliver has a characteristically pithy response: “It’s experiential.”

In rural areas, Sirius can be seen with the naked eye from January through March. In Philadelphia, a telescope is needed, and even then conditions must be right. At the Print Center in Center City, Canicular’s scheduled hours are 7 p.m. to 8 p.m., to coincide with Sirius’s rising. The exhibition runs through March 22.

“We knew we were running a risk being dependent on the weather, but people seem intrigued by the limited hours,” says John Caperton, the Print Center’s Jensen Bryan curator. “It’s creating a buzz! This may be one of the best-attended exhibits we’ve had, despite the fact it’s never open.”

Derrick Pitts, chief astronomer of the Franklin Institute and a (mostly) silent partner in the art show, describes Sirius as “the jewel in the collar of Big Dog, the constellation Canis Major.” Pitts, who trained 10 students from the Science Leadership Academy to help out, arranged Canicular’s live-feed from a telescope on the roof of the nearby science institute.

Outside on Latimer Street is Dwarf: a text-less circular sign with a sound element that Oliver composed on a whistle audible only to dogs. It’s meant to suggest the sun; Dwarf’s red-orange whorls are a photo-collage created from dog fur, a medium Oliver has used before (including in his photo-collage Canis Major). When the sign is lit, the exhibition is open.

“It’s like a speakeasy,” Caperton says of the glowing signal. “You have to be in the know.”

Inside the gallery, Heliometric, a giant telescope constructed of white plastic paint buckets and supported by steel armature, dominates the space. Above, Deutan employs a set of green floodlights and infra-red heat lamps to suggest the green and red colors cast by Sirius—and to give a nod to canine colorblindness. On the stairwell to the second floor is Messier,a digital print of a star chart pierced by a bent paper clip. Diurnal (second floor, South Gallery) holds an eight-channel video display, each monitor an aspect of a moving solar system constructed of umbrella shafts, binder clips, and spools.

The eight video monitors in Diurnal relate to the eight light years separating Sirius from the sun, and the installation itself is a recasting of Oliver’s 2011 kinetic, room-size installation, Orrery. Developed in the 18th century, an orrery is a mechanical model of the solar system. Oliver’s rotating assemblage of items swept off a studio floor is a swash of color and whimsy that suggests the squiggles of Paul Klee in motion.

For the Print Center, a 102-year-old gallery devoted to images hung on walls, Canicular represents a radical departure.

“We’ve been around so long some people have an outdated idea of what we do,” says director Elizabeth Spungen C’83 G’90, who notes that Oliver’s body of work serves as a reminder that printmaking and the photograph “are central to the conversation of contemporary art.”

“There are lots of connections between the photo-based work he used to make and the work he is making now, but the art has become more expansive and more ambiguous,” says Caperton. “So many parts of this show seem as if we’re trying to be difficult. With Demetrius, you’re on your own. The work is not didactic, but it is ambiguous. He’s not acting as an astronomer and he’s not a re-enactor—more like an engaged or an enlightened citizen going to science and art.”

“I enjoy discovering new materials in unexpected places, as in my work Argentum, in which the moon’s albedo became a medium,” says Oliver, referring to both the moon’s reflective quality and to a site-specific installation that required nothing more than gazing at a full moon on the Harlem River. Three years ago, for the Studio Museum of Harlem, he created a photograph of the moon’s reflection on the river that served as an invitation to view the natural spectacle.

It was, he admits, a “tease,” as attested by a program note from the exhibition: “I use the camera in much of my work so it’s worth noting that the moon is also associated with silver, a reflective metal that aids in the production of photography.” By such associative speculations, an installation is born.

Oliver prefers to have the news media’s telescope pointed in another direction. Described as warmly courteous and shy, Oliver, when pressed, calls his reluctance to converse “word economy.”

“Demetrius is extremely private, and a deeply thoughtful person, ” says his friend Michelle White, curator of the Menil Collection in Houston. “He’s interested in using art as a filter or meditation for understanding scientific ideas. He wants to slow things down, bring big ideas into a personal space.”

“Demetrius challenges our perceptions,” says Caperton. “He wants us to see familiar objects in unfamiliar ways.”

Night skies are often involved. “My interest in cosmology is related to my understanding of transcendentalism,” says Oliver, who has been reading Ralph Waldo Emerson since high school. A favorite essay is Emerson’s “Nature.”

Since 2004, he has been concerned with celestial investigations. Nomadic, for example, was a photograph in which he placed miniature lights on the back of a blue jacket, the white spots mimicking stars. It became a series of slide projections. The autumn skies during a complete lunar cycle were critical to Jupiter (2010), the site-specific installation on the High Line billboard at Manhattan’s West 18th Street. A human-sized dog door cropped up in Terrestrial (2013), an installation in which a camera attached to a toy Rover cruised an empty apartment, bumping into bathroom wastebaskets and generally turning the domestic into the surreal.

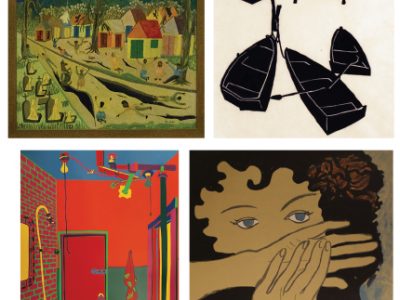

Oliver’s conceptual photo-collages, video, sculptural assemblages, and installations convey a formal precision, even as their reliance on quotidian materials (coal, light bulbs, umbrellas, paper clips, animal pelts) evokes whimsy and surprise. Having earned his MFA at Penn studying with such multidisciplinary figures as Joshua Mosley (professor and chair of fine arts specializing in video design and animation) and the late Terry Adkins (professor of fine arts known for his sound sculptures and assemblages), his early photo-collages were in the conceptual mode of David Hammonds. Employing his own body, Oliver’s work made frequent reference to racial identity and history. In Till, a photo-collage, the artist’s profile is sculpted in chocolate frosting, while in Tracks, his hand, crisscrossed with tracks or stitches, suggests the Underground Railroad.

“The question of identity is still there, says Caperton, “but the conversation has shifted to broader themes in the investigation of self.”

Though racial politics and identity are no longer overt, they cannot be assumed to be entirely absent, says White. And, she notes: “It was really important to the Transcendentalists to go out into nature to understand themselves.”

“When contemplating the nature and structure of phenomena, everything else by comparison becomes trivial and insignificant,” Oliver says. Then he quotes Emerson: “The deepest pleasure comes I think from the occult belief that an unknown meaning and consequence lurk in the common everyday facts …”

Lesley Valdes is a writer and critic living in Philadelphia.