James Mundie has crafted a portrait gallery of “Anomalous Humans” that forces us to confront some uncomfortable truths about the Other and Ourselves.

By Samuel Hughes

We don’t see them anymore, these … prodigies, who once gave rubes a glimpse of huckstered mystery in sideshow tents and halls:

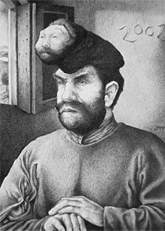

Sealo, the Seal Boy, whose hands grew right out of his shoulders! Chang and Eng Bunker, the Siamese Twins, who married a pair of sisters and fathered 21 children between them! Francesco Lentini, the man with three legs! Not to mention Emmitt, the Alligator-Skinned Man; his bride, Percilla the Monkey-Girl; and Prince Nicholai, all 18 inches and 15 pounds of him …

James Mundie CGS’97 has a deep fascination with these anomalies—not just for who they were and what they represent but for the lavishly strange P.T. Barnum genre in which they displayed themselves. He has portrayed them with something like reverence, driven by a costumed imagination and meticulous craft. The result—this “Curious Collection of Anomalous Humans,” rendered in “Splendid Chiaroscuro”—is somewhere between the photographic portraits of Diane Arbus and a tarot deck by Edward Gorey. The effect is compelling—and unsettling. Yet there is a tenderness at work, too.

“One of the things that really drew people to the freak show over the years was the sense of the Other,” says Mundie, sipping strong coffee in the South Philadelphia rowhouse that he shares with his wife, painter Kate Wilcox Mundie CGS’99, and a couple of brooding cats. “There’s a visceral attraction to those things that terrify us. And in the case of human freaks, people continue to be interested because they feel that, ‘But for the grace of God, that could have been me.’ It forces them to confront their own situation, their own humanity.”

Mundie doesn’t actually call them freaks in the Barnum-style poster that introduces the series. His title is Prodigies: Anomalous Humans, and he has set them in an online gallery brimming with Victorian showmanship (http://www.missioncreep.com/mundie/images/index.htm). But in his introduction to the gallery, he makes it clear that he respects the word as much as the people it’s applied to:

“I chose to avoid using the term ‘freak’ outright because its modern usage has many negative connotations; however, note that among performers the term was considered an honorific … The term ‘freak’ itself is merely a shortened form of ‘freak of nature,’ meaning simply that which deviates from the expected—the exception that proves the rule.” Instead, he uses the word prodigy, which “points to the larger historical view of those ‘strange people’: as portent, the exceptional or marvelous thing that inspires fear and wonder.”

“The Golden Age of the freak show was really the Victorian era,” explains Mundie, whose mellifluous voice has a hint of carny showmanship. “Someone like P.T. Barnum, who really took it and changed it. This art form, if you will, this theatrical form that was thousands of years old, he suddenly turned it into show biz, and found a way to market it and really make it popular entertainment. I want to honor his vision and also that era.”In the spirit of the circus or carnival sideshow, where even a three-legged man would be re-invented to appear more interesting, I have created new “histories” for my subjects in which fact and fancy are liberally mingled. The freakshow, with its quasi-religious overtones, has a theatrical heritage of stylized performance and presentation that dates back many centuries. Very often, a great deal of fraud was involved, but this seemed only to delight patrons all the more.—From the introduction to Prodigies.

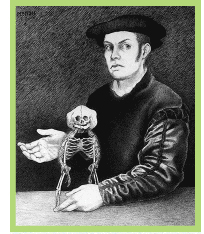

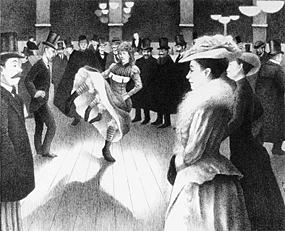

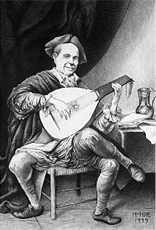

One might think of Mundie as a Two-Headed Man—half carny-phile, half art-history aesthete. He is almost frighteningly articulate for a young artist, and he portrays his prodigies in exquisitely artful settings—an anonymous Bearded Lady as Vermeer’s “Lacemaker,” for example, or Myrtle Corbin, the Four-Legged Girl from Texas, dancing at the Moulin Rouge in the style of Toulouse-Lautrec. For Mundie, that context is a vital component of the portrait.

“That’s part of the series—my love of certain paintings, their history,” says Mundie, who has taught printmaking and drawing at the Fleisher Art Memorial in Philadelphia. “Some think of it as a parody of the painting; I think of it more as an ode, honoring that work.”

When he gets stuck on a particular drawing, he’ll put it aside and start flipping through old monographs and art-history books, letting his subconscious do the walking. Eventually, it reaches its unexpected destination.

“I may find some obscure Renaissance painter that no one’s ever heard of, or a painting I’ve never seen before, but there’s something curious about the sitter’s gesture—or what they’re wearing, or something in the background—that reminds me of a circus performer,” he explains. “It’s like this wonderful puzzle for myself, this challenge to find something to honor both the painting and the person, and bring them together to create something new out of it.”

Given that both art history and sideshows have their own formal conventions and traditions, this “blending of the aesthetic and the macabre is a natural pairing of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture,” Mundie writes—“especially since both appeal to one’s voyeuristic inclinations.”

Mundie’s prodigies are “often grotesque, to be sure,” wrote The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Edward Sozanski, “but they’re also drawn, in pen and ink, with an astonishing facility that in an odd way makes them sympathetic rather than objects of morbid curiosity … By inserting his subjects into historical contexts, Mundie tests his audience’s tolerance for aberration.”

The tolerance does get tested. When asked by the Gazette to assess Mundie’s work, Dr. Christine Poggi, associate professor of art history at Penn, found his introduction “quite disingenuous,” arguing that his portraits are part of a tradition of viewing physical deformities as “signs of mental or physical atavism, moral insanity, and so forth.

“The freaks at carnivals were hardly honored, but cruelly put on display,” Poggi adds. “He appeals to our prurient interest, delights in it, and seems willfully unconcerned about those who bear the burden of being considered anomalous or pathological. There is a long history of this sort of representation. It is not at all innocent.”

Not surprisingly, Mundie doesn’t see it that way.

“I want people to feel challenged by these images and to acknowledge and examine their own reactions, confront their own ideas of beauty,” he says. “Those with a very narrow conception of beauty cannot get beyond the misshapen bodies of my subjects. Are these people not worthy of consideration? Should they be locked away from prying eyes?

“To dismiss the role of performing freaks as ‘decadent’ or ‘prurient’ is to deny history, deny human nature, and deny these people a voice,” Mundie adds. “My portraits may titillate, but they are also undeniably beautiful portrayals of interesting people in an incongruous setting. The drawings should inspire dialogue rather than outrage.”

While he acknowledges that freak shows are viewed as “distasteful” in polite society, he insists that he is not mocking those who have participated in them. “In fact, my portraits honor these people as individuals and performers who played a very specific and stylized role that has been part of human civilization for millennia. Some were coerced and exploited, that is true; but many found the freak show the one place where they could earn a decent living on their own terms and achieve a level of acceptance, if only among their fellow carnies.”

The freak shows are mostly gone now, doomed by economics and the mores of our age. A couple of decades ago, Otis Jordan—also known as the “Frog Boy” and the “Human Cigarette Factory” (on account of his ability to roll and light a cigarette using only his lips)—was temporarily law-suited out of business by a woman who found his performance an “intolerable anachronism” akin to “pornography of disability.”

“I can’t understand it,” Jordan was quoted as saying at the time. “How can she say I’m being taken advantage of? Hell, what does she want for me—to be on welfare?”

“This is one of those ironies that surround the sideshow,” says Mundie. “People want to stop these people from being exploited, yet they can’t see how the performers are often the ones in control of the exploitation, and manage to turn an adverse situation to their advantage.

“A lot of people who work in freak shows realize that, ‘People are going to stare at me; I can’t stop that. So why don’t I make them pay for the privilege?’” he adds. “So one can look at it not as exploitation but empowerment, or rather turning exploitation on its ear—because really, now this person is exploiting the audience. Nowadays, even if people wished to exhibit themselves, they would be unable to do so. In some cases there are actual local statutes against the presentation and exhibition of human anomalies.”

There’s another reason for the demise of the freak show.

“One has to consider that with advances in medicine, many of the genetic anomalies that might predispose someone to enter into show biz simply don’t occur as often,” notes Mundie. “Or maybe sadly, someone who has the ability to determine if the fetus is going to be deformed, may very often abort it.”

What have we lost by keeping these anomalies off the stage and out of sideshow tents? In Mundie’s view, quite a lot, though he knows that many of the rubes who went to freak shows didn’t exactly go to become enlightened.

“They went for a cheap thrill,” he concedes. “And there’s room for that as well—obviously that’s why these things were so popular, and that’s how they made their money.”

But without the ability to experience firsthand what these anomalies offer, “we lose the opportunity to learn something about ourselves that could only really be learned in those circumstances,” he argues. “You can see a picture in a book; you can watch a film; but it’s not the same as being there in that room, making the choice to walk in, walking up close to the person and perhaps speaking to them, hearing them tell their tale. There’s that sense of theater and mystery—actually walking into the tent, like an initiation rite: I’m paying for the privilege of being let into this wonderful secret! Most of the time that secret was a complete scam. But that was part of the fun of it.”

Mundie has been exploring the mysteries of art since he was old enough to hold a pencil. As a kid he checked out his full share of books on Renaissance painting from his local library in New Britain, Pennsylvania. (“I don’t think I really understood the symbolism in these works at the time,” he admits, “but they spoke to me on a personal level.”) He has yet to kick the habit of perusing art books, and he and his wife have amassed a “very respectable personal library of monographs,” to which he is constantly referring.

Along with a lifelong fascination with beauty, he says, he has always been attracted to the “weird and uncanny.” That includes ghost stories, horror movies, and the sort of oddities found in Ripley’s Believe It or Not and the Guinness Book of World Records—especially such human anomalies as Jojo the Dog-faced Boy (“hairiest man in the world!”) and James Earl Hughes, once the world’s fattest man (“buried in a coffin the size of a piano case!”). Those images, he says, “were forever burned into my visual memory.”

It was the ornamental side of Franklin’s vision that brought Mundie to Penn, where he started to take courses while still enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Along with the required art-history classes, he found himself drawn to folklore and other absorbing but not exactly “useful” courses.

“I often found the most obscure and out-of-the-way things the most intriguing, and I would try to find an unusual way to approach the subject,” he says. One instructor of a “particularly mind-numbing course on Third World architecture was quite baffled but pleased when I presented a research project on Dogon architecture in the form of a comic book.”

On the whole, his experiences at Penn taught him that “few things in life can or should be compartmentalized,” he adds. “An understanding of one topic—even one that seems obscure—may lead to discovery in another. Everything is connected, and the trick is to find those points of interaction. That openness to possibility helped spawn Prodigies.”

Around the time he graduated from Penn in 1997, Mundie began working on a series of woodcut portraits, and soon found himself wanting to try something “a little off the beaten track.” He kept thinking about Jojo the Dog-faced Boy and the other freakish images from his childhood, and was curious to see the old photographs again. He wasn’t having much luck tracking them down until his wife remembered a book of photographs of unusual people that she had seen years before. It was Freaks: We Who Are Not as Others, written by the late Daniel P. Mannix C’35. Mundie was quickly hooked.

“I started to read about these people’s lives and was completely wrapped up in the spooky visceral chill of their other-ness,” he says. “Here were people that, due to chance genetic mutation, were segregated from society, but also sought out to perform a special stylized role. This was the primordial theater of the macabre—horror, fiction, tragedy, and comedy rolled up in one uncanny and taboo subject.”

In his mind’s eye, Mundie originally saw these portraits as etchings. Since he didn’t have access to a printing press or acid, he decided to work out his ideas in drawing form.

“I was thinking, ‘OK, this is just an immediate way I can get this out, and eventually I’ll return to them as etchings,’” he says.

Instead, the drawings took on a life of their own.

“There’s a quality to the drawing that I cannot get in the etching, but at the same time a lot of people remark on how the tones I’m achieving in the drawing mimic the sort of lush tones that you might get in an aquatint or a mezzotint,” he notes. “That may be a subconscious thing, because I wanted so much to be working on etchings that I found myself handling the pen as I would an etching needle, inscribing a plate, stippling—doing all those things that normally one would get in aquatints.” (For the record, an aquatint is an etching process that can produce several different tones by varying the etching time of different areas of a copper plate. A mezzotint involves scraping or burnishing areas of a copper or steel plate to produce effects of light and shadow.)

Mundie spends months on each portrait, though he is usually working on more than one at a time.

“There’s a sort of anal-retentive quality to my personality that I spend so much time laboring over these things,” he admits. “But it’s a lot of building up of delicate textures and manipulating tiny little strokes of the pens—to the point where my wife thinks I’m insane.”

The images that became Prodigies grew out of several interests, he notes: an affinity for portraiture, a passion for art history, and a “natural curiosity for pathology.” He has amassed a trove of stories about the characters he’s portrayed, as well as an impressive collection of cards, photographs, pamphlets, and other freak-show paraphernalia, some of which can be viewed on his website.

“I started this series in ’98, and I’m still working through it,” he says. “A lot of people, when they saw the initial series and I had done the first 20 or so drawings, said something to the effect of, ‘Well, how far can you take it? You’re going to run out of freaks eventually.’ And I’m like: ‘Not necessarily—not in this world!’”