An innovative, interactive exhibit at the Penn Museum traces human evolution—big brains, back pains, dental problems and all.

By Beebe Bahrami | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar | One Big Family Celebration

We were all waiting in the Upper Egyptian Gallery—diverse Philadelphians, Penn students, faculty, and staff—for the next speakers to arrive on the podium for the Darwin Day celebration at the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. It is an annual event, falling near Charles Darwin’s birth on February 12, 1809. Dr. Michael Weisberg, a philosopher of science and Penn assistant professor of philosophy, had just finished giving a public talk on “Evolution and the Environment.” The next talk, “Evolution in the Courts: The Story in 2008,” was about to begin. It was presented by Eric Rothschild L’93 and Steve Harvey, the lawyers who successfully represented the plaintiffs in the Dover, Pennsylvania, “intelligent design” case [“Intelligent Demise,” Mar|Apr 2006]. The man sitting in front of me suddenly turned around and said to anyone who would hear, “It’s important to listen to all sides of the debate and then determine what you’re going to believe.”

And there in a nutshell, it seemed, was the source of the ongoing polemic pitting creationism against evolution. Even many well-meaning, informed people get tripped up on the idea that this question has anything to do with belief. But it is not about belief. It is about presenting the evidence for evolution and how it works.

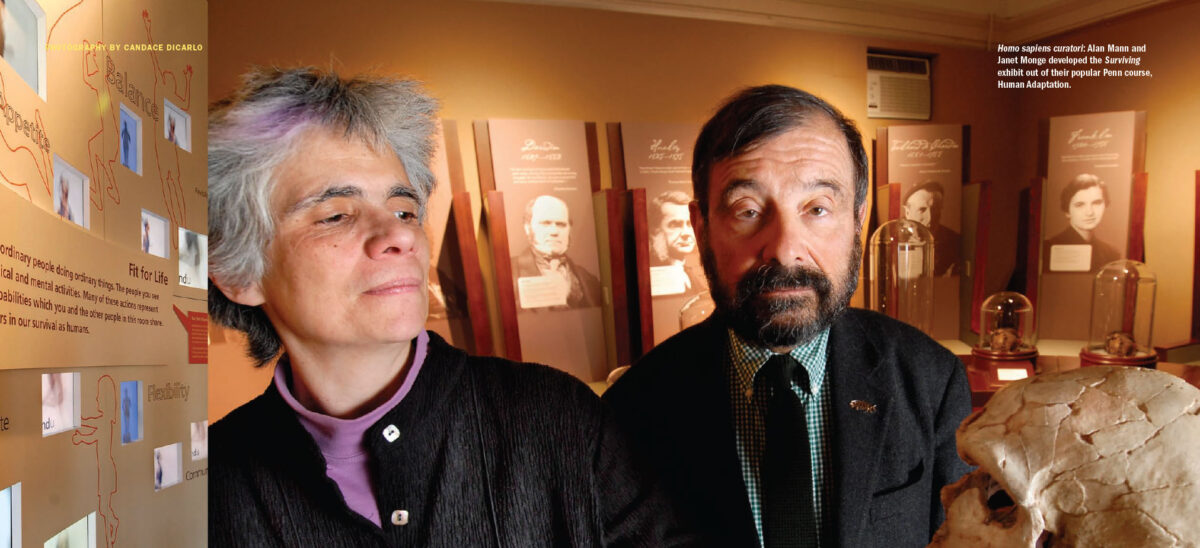

Surviving: The Body of Evidence, a new exhibit that will run through May 2009 at the Penn Museum, does just that. Funded in large part by the National Science Foundation, along with many other individual and institutional contributors, Surviving is a highly engaging, interactive, multimedia exhibit on human evolution co-curated by physical anthropologists Janet Monge G’91 and Alan Mann.

Monge is acting curator of the physical anthropology section of the Penn Museum, keeper of the physical anthropology collection, associate director and manager of the museum casting program, and an adjunct associate professor in the anthropology department. Mann was a professor of anthropology at Penn from 1969 until 2001, when he joined Princeton’s faculty, as well as curator emeritus and a current research associate in the Penn Museum’s physical anthropology section and director of the museum’s casting program.

In the works for more than five years, Surviving involves all the departments of the vast Penn Museum. After its run in Philadelphia, the exhibit will travel to at least 10 cities, with the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and the Heath Museum in Houston scheduled as the next stops.

But the genesis (as it were) of Surviving goes back even further than that, and represents the synthesis of decades of dedicated teaching. It began with Alan Mann’s quest for an effective way to teach his students—in a popular course called Human Adaptation—how best to see and understand the evidence for human evolution.

Mann began teaching the course in the 1970s, joined by Monge about 20 years ago. “We realized what we were talking about was how we fit into the natural world,” he says. For example, consider the common human problem of back pain, caused by the fact that “we have an extremely elegant way to move—walking upright. No other animal has disk-degradation problems. Why does it break down?” Over the years Mann and Monge worked out a way to address the issues of how we came to be as we are—both our elegance and our problems—by looking at humans from the long gaze of evolution.

In reflecting on the Human Adaptation course, Monge notes that that there have been a number of creationists among their students over the years—“People who would say, ‘Yeah, I came into this class full-well thinking there was just no way I was ever going to come away with any kind of an understanding of evolution except in a negative sense,’ and [afterwards] they said, ‘Hey, nobody ever showed me the data.’ You know what I mean? Show me the data. And also explain data, interpretation, and theory with a very real kind of an example.”

With Surviving, Mann and Monge have gone more public with their dynamic approach to teaching about human evolution. For anyone raised on traditional museum displays centered around objects with labels, the exhibit is something of an evolutionary leap in itself—one in which the visitor brings the most pertinent item to be studied, his or her own body and mind. Surviving is a multimedia, interactive world in which your body is the central exhibit: You carry within you all the evidence required. The exhibit’s thought-provoking activities and displays are designed to make visitors see themselves in a different light.

The curators first worked with Toronto-based exhibit designers Reich + Petch Design International (www.reich-petch.com), along with exhibit interpreter, Ruth Freeman of Blue Sky Design, in a series of eight two-day long workshops to hone and shape the exhibit to put the visitor at the center of the journey through human evolution. Then Reich + Petch designed the exhibit and another Toronto-based company, the House of Kevin (www.houseofkevin.com), built it. The interactive and audiovisual aspects were created by Chedd-Angier-Lewis Production Company (www.chedd-angier.com).

“Most people don’t understand evolution because they might have a concept of dinosaurs or they might have heard something or other about Darwin and it might have gotten all confused,” Monge says. Add to that the religious content, a “constant part of the general rhetoric out there,” she says, and the confusion can become greater still. “If you individualize the information, it makes it just much more comprehensible. I mean, people just have so many misconceptions about evolution, it’s actually really scary.”

While it may surprise some of those caught up in the polemic, Monge places the blame for this situation “squarely on the shoulders of probably three or four generations of scientists who never had the urge to move beyond their own walls and try to communicate this effectively,” she says.

Monge estimates that she gives between 50 and 60 lectures a year to high-school and other nonprofessional groups as “a community service,” she adds. “Not to do that would be, in my own mind, morally reprehensible.” Not that people are consciously thinking, “‘I’m going to be morally reprehensible today,’ but you have to take those moments to really integrate communities,” she says.

“You’ve got a creationist museum and they’re [showing] humans walking beside dinosaurs, and further engraining these notions of the fallacies of evolution. If we can’t generate a meaningful exhibit or even produce meaningful talks” that can at least get people who hold such beliefs to look at them somewhat more critically, “then we haven’t done our damn job,” she insists. “We wouldn’t do that to our students; why would we do it to an educated public?”

(Monge recalls that, in her own education in the Catholic school system in Philadelphia, “evolution was introduced to the curriculum,” she says. “I subsequently found—while at college—that I had had a better introduction and understanding of evolutionary processes than virtually any of my cohort.”)

In broader terms, the exhibit is a reminder for even those who accept the evidence of evolution that the process is still going on—and humans are not exempt from its effects. “We live on a planet in a web of life and that means all of these other things are impinging upon us and they are not controllable,” Monge says. “They’re not predictable and they’re not controllable. Including culture. And the thing is, culture creates as many problems as it actually resolves. People don’t understand that. They see it as the great insulator.

“You have a planet where everything is undergoing evolutionary change,” she adds. “What would make you think that humans are so wonderful that we could alter things that are planetary in nature? It’s like a species-based denial.”

The essential mission of Surviving, says Mann, is “to make sure that everyone understands that evolution plays an [important] role” in their lives. “The focus of the exhibit is that we’re survivors but that we’re not perfect. As a result, we have problems.” After mentioning such pieces of evidence for our evolution as molars and sciatica, Mann adds one more: “If we were created in God’s image,” he notes, “then God [clearly] hasn’t had a Caesarean section.”

Surviving is built on six sections that stack and support each other like vertebrae.

The first part, “Fit for Life,” is something of a celebration of all that is splendid about humans, such as our versatility and flexibility, our ways of communicating, our diverse omnivorous diet, our endurance, our balance, and our dexterity.

Next, “Our Place in the Natural World” shows humans’ relatedness to all life on earth. One highlight is meeting the 210-million-years-old Morganucodon, one of the world’s earliest mammals and our earliest mammalian ancestor discovered in the fossil record. All mammals share with Morganucodon the traits of being viviparous, or live-bearing; nursing their young with milk from mammary glands; being warm-blooded and covered with some form of fur; and possessing special teeth and jaws for chewing food up before swallowing.

In this section, visitors can view the evidence for the primate line of evolution that branched off from other mammals around 55 million years ago, and trace their own development since our ancestors branched off from some common primate ancestor a mere 7 million or so years ago, giving rise to several hominid species, including us.

They can also compare humans to other creatures, like chimpanzees, raccoons, cats, deer, dogs, gorillas, and bears. Look in a mirror and explore whether your teeth look more like a cat’s or a chimp’s. Learn why you see a red fire hydrant differently than your dog does. Discover that you and a chimp have the same number of hair follicles per square inch of your body—the chimp’s hairs are just more noticeable. And watch the other Homo sapiens visitors play and have fun with all these exploratory activities.

Also available for investigation is the physical evidence for similarities and differences between humans and other primates. Like our primate relatives, we have forward-looking eyes, omnivorous dentition, flexible hands and toes, and nails and sensitive finger pads instead of claws. On the other hand, humans’ pelvises are wider and not as long as those of our closest primate relative, chimps, a configuration that allows us to carry the weight of our upper bodies and walk on two legs all the time. It also means that our legs angle in from our pelvis to our knees and then go straight to the ground from there. We can carry our children or heavy loads of food or gathered wood. We can run and throw a spear. We can gesture to each other while we walk.

The third part of the exhibit, “Finding Your Human Ancestry,” goes more deeply into the details of those past 7 million years of human evolution. On hand are fossil casts of famous African, Asian, and European hominids made by the museum’s casting program. Over 200 of these durable epoxy casts are in the Surviving exhibit, and many of the displays can be touched, allowing visitors to not only see the evidence but to feel it. (In all, Monge and her colleague in the casting program, museum volunteer Lisa Gemmill, have created some 3,000 molds and casts covering the stretch of human evolution, many of which are loaned to institutions worldwide for their own exhibits.)

Included in Surviving are casts of the remarkable footprints preserved in volcanic ash made by three bipedal hominids with feet like ours who sauntered through a part of Tanzania, East Africa, around 3.7 million years ago; a skull cast of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, unearthed in Chad, and a cast of the femur of Orrorin tugenensis, from Kenya, both casts representing our oldest known hominid ancestors going back 6 to 7 million years; the diverse australopithecines (including Lucy, from Hadar, Ethiopia, dating from about 3 million years ago); Homo habilis and Homo erectus, both dating to around 2 to 1.5 million years ago; and on to early modern humans and Neanderthals, as well as modern humans.

Having all these family members in one space helps the visitor fully grasp the longterm trends of human evolution: an enlarging brain size and cranium in conjunction with a jutting larger face that starts to get smaller to fit under the brain; a mouth that likewise goes from big (when jutting out from the face) to small in order to fit in the new alignment under the larger cranium; a clearly upright mode of walking with forward-facing toes and a less flexible big toe than other apes; and a pelvis that is wider (to be able to support upright walking) but not so wide as to lose the efficient angle between the knee and hip joint that allows efficient bipedal movement. Less tangible but simultaneous trends include development of language and complex thought, physically evident in the form of early tools and works of art such as the Venus of Willendorf figurine, as well as certain expanded areas of the brain.

“Witnessing Evolution,” the fourth section, offers the actual words—in dramatically performed audio displays—of famous scientists who have contributed to our knowledge of life on earth. These luminaries include Carolus Linnaeus, Charles Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, Joseph Leidy M1844 (professor of anatomy and founder of Penn’s department of biology), Jesuit priest and scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (who said, “Christ is realized in Evolution”), Rosalind Franklin, and Mary Leakey.

By the fifth section, “We Are Not Perfect But We Are OK,” things start getting personal. Though we are successful creatures because we are still here and still evolving, our bodies have some limitations shared by people all over the world—and some of these imperfections are also evidence of the path our evolution has taken.

This part of the exhibit features “Ms. Big,” as Mann and Monge call her—a high-tech mechanical model of a modern human female measuring 16-feet from head to toe. One side of Ms. Big’s body is on rails; you can move her limbs to see how arms, joints, hips, knees, and legs work. On the other side are x-ray-like interactive displays that allow a deeper inquiry into our evolutionary anatomy. How our bodies work—both the grace and the imperfections—can be explored via the multidimensional giant or thematic sections set up on the edges of the giant’s space.

That nagging lower back pain, for instance, is the consequence of our s-curve, required to position our spine upright over our pelvis. Also, while many of us still inherit the set of 32 teeth our earliest ancestors had, albeit on a smaller scale, these teeth must fit within our smaller faces and mouths. The resulting tight fit often leads to removal of our wisdom teeth (one way human culture intervenes with its biology). And there are more imperfections, from the development of osteoporosis as we age, to the risk of stroke from our large brains that require a reliable supply of a lot of blood to keep functioning, to that troublesome runner’s knee or tennis elbow.

Perhaps the most fascinating evolutionary complex and imperfection concerns our big brains, pelvises, and giving birth. First, as we evolved to be two-legged walkers, our hips could only get so wide before compromising the angle between the hip and the knee that makes walking on two legs possible. Next, our brains also evolved into a bigger size than those of our ancestors of a few million years ago.

Two “solutions” to the big-brain-small-birth-canal dilemma evolved: the skull bones in human infants don’t suture until after birth, allowing the edges of each plate to overlap as the head passes through the birth canal; and the human baby is born more helpless than most animals’ young because its brain doesn’t grow to its full capacity until after birth: in the first year of life, a newborn’s brain doubles in size.

This, says Monge, is a “great example of selection for increases in brain size eventually both producing and solving the ‘obstetrical dilemma.’ [Here is] a species that, without modern medical intervention practices, has negative maternal/infant birth outcomes 20 percent of the time. One solution [is] the production of immature offspring that are so underdeveloped that they are best described as extra-uteral fetuses! The biological and social implications of this affect us to the very core of our humanness.”

Our development of culture can intervene in solving problems that arise in the environment and with our bodies. Caesarean sections, artificial joints, jogging, diet programs, and antibiotics are all examples of how we interact with our biology culturally. Though they are having an effect on our evolution, we can hardly begin to predict how.

In the sixth and final section of Surviving, “We Keep Evolving,” both visitors and experts are invited to contemplate what our evolution might look like in the future. What might be the effect of population growth? Genetic manipulation? Natural disasters? The outbreak of a globally spreading disease? Large-scale war? Human-induced environmental alterations?

Which brings up another reason for the urgency of understanding our place in the web of life. “There are deep implications for being aware that we evolved a certain way,” emphasizes Mann. “Our future depends on our ability to recognize our place in nature. If we don’t successfully get at that, we will have the future of another species and become extinct.”

Beebe Bahrami Gr’95 (www.beebesfeast.com) is a frequent contributor to the Gazette. Her book, The Spiritual Traveler Spain—The Guide to Sacred Sites and Pilgrim Routes, will be out in the spring of 2009 from HiddenSpring Books/Paulist Press.

Further Information

- On Surviving and on evolution: www.Surviving-PennEvolutionExhibit.org. This site is also going to be an extensive resource for teaching evolution.

- On The Year of Evolution: www.yearofevolution.org. Check back regularly as new events are added.

- On the Penn Museum’s casting program: www.PennFossilCasting.com.

SIDEBAR

One Big Family Celebration

In tandem with Surviving, Penn and other local institutions will be offering a host of events for the Year of Evolution in 2008-2009, which marks the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth (February 12, 1809) and the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species.

“The Darwin bicentennial is a world-wide event which will be celebrated at many institutions of learning,” says Dr. Howard Goldfine, professor of microbiology in the School of Medicine, and co-chair, with Dr. Michael Weissberg, assistant professor of philosophy, of the Year of Evolution committee. “Philadelphia and Penn is a great place to have this happen. We have a strong, vibrant scientific community with deep interests in evolution and its consequences in biology. In addition we have a long history in evolution.

“In the mid-19th century, Philadelphia was one of a few major intellectual centers in America. Joseph Leidy [M1844, professor of anatomy and founder of Penn’s department of biology] corresponded with Darwin, and Samuel S. Haldeman [professor of natural history at Penn from 1851 to 1855] provided important evidence on variation in species that Darwin had read and cited. Edward Drinker Cope [who studied medicine at Penn and served as professor of geology and paleontology] and Ferdinand V. Hayden [professor of geology and mineralogy, for whom Hayden Hall is named] explored the West and provided many fossils to Leidy and other paleontologists, which showed that species appear and disappear in the fossil record and that this record is very deep and ancient.”

Scholars such as Donald Johanson (director of the Institute for Human Origins), Spencer Wells (director of the National Geographic Society’s Genographic Project), and authors E. Janet Browne (Charles Darwin: Voyaging and the Power of Place) and Kenneth R. Miller (Finding Darwin’s God: A Scientist’s Search for Common Ground Between God and Evolution) are scheduled to participate in some Year of Evolution events. And the Penn Reading Project has selected a book on an evolutionary theme (Your Inner Fish, by former faculty member Neil Shubin) for incoming freshmen to read and discuss during their orientation weekend in September.

Among the institutions partnering in the effort are the Philadelphia Zoo, offering an up-close look at our living primate relatives, and the American Philosophical Society, which will mount an exhibit on Darwin’s work. The Mütter Museum will provide a special evolutionary perspective on its medical collection; the Franklin Institute’s IMAX theater will show related movies; and the Academy of Natural Sciences will have an exhibit on geneticist Gregory Mendel’s work. Monge, despite having her hands full with the Survivingexhibit, making casts, and teaching, has also been instrumental in the citywide efforts in planning the Year of Evolution.

When Charles Darwin first arrived at the synthesis of his observations that became his theory of evolution, the evidence was already piling up. Since then, the case supporting it has become ever more airtight. “Evolution is one of the core tenets of modern science,” says Weisberg. “Rapid progress in all of the life sciences—from molecular genetics to HIV prevention—depend on evolutionary principles. Basic scientific literacy requires a working knowledge of evolutionary principles. But I also think that evolutionary biology helps us understand more about who we are as a species and our relationship to the rest of the life on this planet.”

Weisberg calls the discovery of common descent— one of the basic evolutionary principles—“one of the most important discoveries in all of science. And to me, it leaves us with a beautiful image,” he concludes. “All the life on this planet is connected. We are all literally one big family.”—B.B.