A new Penn study digs into the science behind baseball’s “magic mud.”

As a principal investigator at the Penn Soft Earth Dynamics Lab (Penn SED), Douglas Jerolmack has studied everything from the flow of rivers to the shifts of dunes. But his latest research project really knocked it out of the park.

Seeking to understand the secret sauce behind the celebrated “magic mud” that professional pitchers apply to baseballs to improve their grips, Jerolmack and his research colleagues at Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and School of Arts and Sciences found that the mud contains just the right mixture of clay and water to uniformly coat the baseballs with an adhesive residue, and just enough sand grains to enhance friction. “There’s essentially two things the mud needs to do,” he elaborates. “First, it has to be spreadable, so you can smear it on and thin it out. Think of shaving cream, or ketchup. Then, once it dries, it has to enhance your grip but not inhibit your ability to let go of the ball, so it can’t be sticky.”

For Jerolmack and his coauthors on the study that appeared in November in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences—including Penn SED postdoctoral researchers Shravan Pradeep and Xiangyu Chen EAS’25 and Penn Engineering professor Paulo E. Arratia—unpacking the mud wasn’t just a sporty endeavor. It may also be useful in understanding why some environments are more susceptible to natural hazards such as mudslides, as well as in improving sustainable building techniques, Jerolmack says.

Jerolmack, who’s also the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor of Earth and Environmental Science, wasn’t all that keen on baseball when he was introduced to the mud by way of a query from a curious sportswriter a few years ago. Sifting through the many articles that have been written on the goop, “I found zero science,” he says. “They just assumed it scuffs the baseball and removes the sheen. But … how? No one bothered to go look. We smeared the mud on a baseball and then wiped it off—and there were no marks, not a scratch. It turns out that what everyone reports is not correct. So, I sat up and said, Now, I’m interested.”

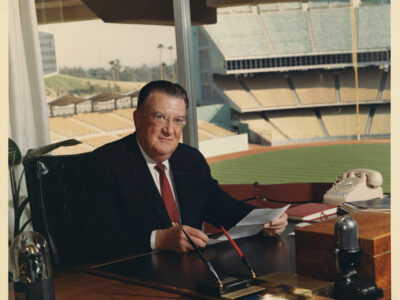

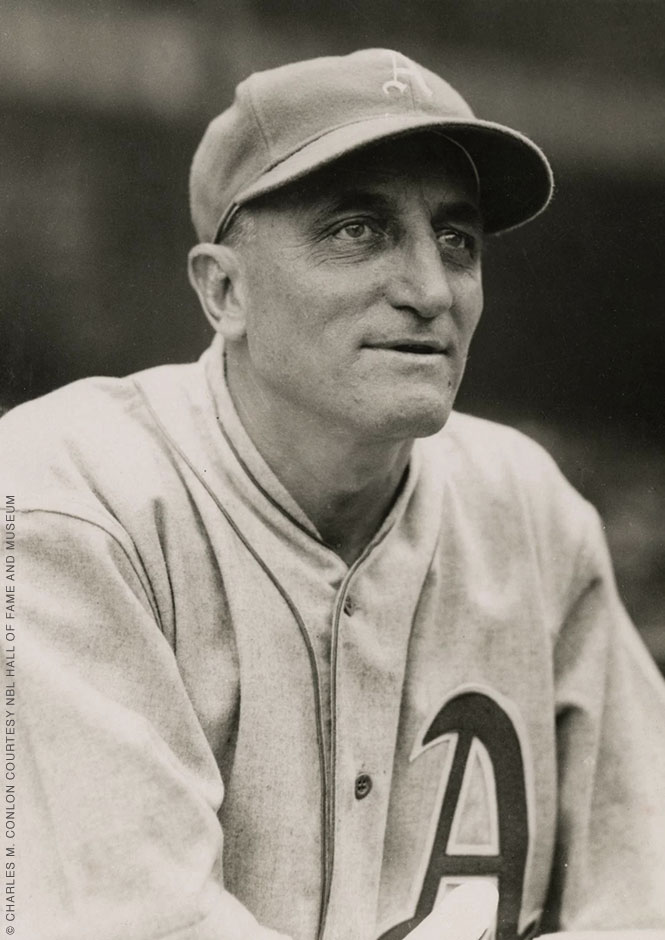

The legacy of the mysterious mud has captivated baseball’s notoriously superstitious fans for almost a century. The history stretches back to the 1920s, when Major League Baseball’s honchos began requiring that balls be roughed up after a pitch killed a batter. They tried infield dirt and saliva from chewing tobacco and neither did the trick, but eventually Lena Blackburne, a former player and then a third base coach for the Philadelphia Athletics, thought of the New Jersey mudbanks along the Delaware River where he had played as a kid. The mud scooped from that site worked so well that it’s been used by Major League Baseball (and most minor leagues) since 1938.

Today, Lena Blackburne Rubbing Mud is run by the same family (the Bintliff family) to whom Blackburne’s successor passed the business, and both the location and specific contents of the mud remain closely guarded secrets. Even Jerolmack has never visited the site. “Of course, I’m always very interested in being in the field or on the river to understand the processes and deposition in nature,” he says. “When I learned that the family keeps the source secret and that there’s been talk about Major League Baseball one day replacing it with a synthetic version, it all seemed so loaded that it seemed insensitive of me to threaten this tradition.” Choosing among two research directions—the specific site characteristics that make the mud special, and how the mud works—he opted for the latter. “Interestingly, at that point, it became important not to talk to the family,” Jerolmack says. “We wanted to buy it from the website like anyone else, then take it and blindly subject it to rigorous tests in the lab.”

Opening the Vaseline-sized jar that arrived in the mail, he grabbed a dollop of the substance, which looked like “straight-up mud, though I could tell it had been processed because of its uniform, non-clumpy consistency,” he recalls. “We held it upside down and it didn’t drip, it didn’t feel gritty, and it smeared and spread easily.” All mud has common properties, he adds: it contains clay, the amount of which varies from site to site; it contains water; and it usually contains some kind of larger particles, like silt. Jerolmack and the other researchers played with, if not in, the muck for two years of continuous experimentation to get to the bottom of it.

First, they measured friction by pressing a baseball into an instrument and then spinning it to measure the resistance that produces friction. “But in this case, it knocked the sand grains off the baseball, which isn’t what a hand would do since fingers are squishy and moveable,” explains Jerolmack. So, using a polymer, the team created a ‘finger’ they dabbed with an oil called squalene to simulate the fluids emitted by a sweaty pitching paw.

Their conclusions, as reported in the paper, indicate that the mud creates a smooth baseball surface by filling in pores in the leather, and that a small amount of angular sand grains bond to the baseball, leaving a studded surface that enhances friction. “The proportions of cohesive, frictional, and viscous elements create a soft material with an unusual mix of properties, that could find other applications in the development of sustainable geomaterials,” the authors wrote.

Meanwhile, the extra je ne sais quoi of this particular mud remains a mystery. “This family harvests the mud naturally, but we know they drain and sieve it a bit and they report that they add a proprietary compound,” Jerolmack says. “We don’t know what that is, but we suspect they need to add a disinfectant and then maybe a polymer or something that makes it clump and behave in a certain way. We didn’t look for that; it’s proprietary but also outside of our wheelhouse. The family relies on an extraordinary amount of knowledge to get everything just right and bring it to the required sweet spot.”

While Jerolmack expresses surprise that MLB hasn’t yet come calling, he suggests that there’s not much sense in muddying up the works. “This is a 90-year-old tradition, sustainably produced in small batches by one family-owned business,” he says. “It’s doing fine. Why would you want to replace it with something that would require some sort of production? It’s been one of the most consistent things in baseball and that seems important.”

—JoAnn Greco