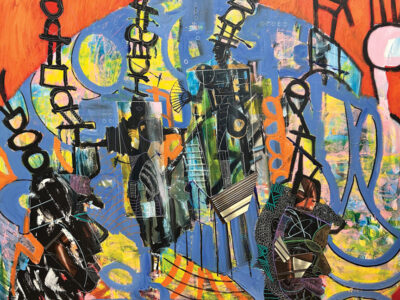

An Indian-born artist celebrates the richness of color in his work and life.

Natvar Bhavsar GFA’65 likes to say that he was “born swimming in tubs of color.” A native of Gujarat, India, he comes from a family of textile printers.

“Whenever I went to my grandmother’s house, I was surrounded by deep, deep indigo and crimson dyes,” he recalls. Each spring, his Hindu community celebrated Holi, a festival of color in which powdered inks are thrown on revelers, creating a human rainbow.

No surprise, then, that he takes color seriously. The soft-spoken 83-year-old artist is known for eye-popping color studies that tease the viewer into looking deeper to discern subtle gradations and textures.

He views the process of painting as both an investigation and a journey: “taking a walk in the wilderness.” As he begins each exploration, without any preconceived notion about what he will find, every colorful revelation pushes him onward, as if drawn by an “internal force of nature.” Often, he will paint for whole days at a time before he resurfaces back into the world. His largest painting took three months of 18-hour days to complete.

His paintings are not created in the traditional way with brush and liquid color. Instead, he deposits powdered pigments, layer by layer, into a moist gel on the canvas—“in the way that rain falls, or how snow falls,” he explains. “When you buy a paint, it’s made up of chromatic colors and the glue and some added material. The dry pigments I use are … very high quality in order to produce a kind of richness in my art. That way, I feel, you are really not diluting it.”

Over the years, Bhavsar has invented certain tools or had them specially made: 12-foot-long brushes, large petroleum-distillation screens, silk pouches for dispersing color. These devices give him precise control over the color and where it is directed, he explains. “I have, in some way, enlarged the vocabulary of how to move the color to do the work for you.”

As George S. Bolge, CEO of the Museum of Art in DeLand, Florida, puts it, Bhavsar’s “large, amorphic paintings” have the ability to draw us in “much as the landscape canvases of the 19th century transported us into untamed forests, spectacular mountain vistas, or vast, empty plains.” Bolge calls Bhavsar a “visual poet” in a brochure for a recent exhibition at the DeLand museum and says his paintings enchant because they evoke “things we can sense but never quite see.”

As a child, says Bhavsar, “I was precocious. A high achiever, you know? My basic nature is that I have an enormous love for knowing things and doing things.”

His father was headmaster of the village school, and Bhavsar was a top student in all subjects. Then, when he was 10, his father died. On top of that, he says, “my community’s whole financial structure sort of collapsed because India was becoming independent at the time.” Suddenly he was forced to become a breadwinner for his family.

Having enjoyed art ever since his teacher pinned his pencil copy of Manet’s “Young Flautist” on the wall in eighth grade, he began teaching the subject at age 19, barely older than his students. Through his employer, he gathered more training and eventually earned a bachelor’s degree from Gujarat University.

A family friend urged him to study English and go to America, Bhavsar recalls. The planets aligned, and with the help of that family, he secured a visa and enrolled at Penn in the early 1960s. To support himself and finance his brother’s education, he worked part-time at a Philadelphia automobile-upholstery manufacturer.

“It was very unusual when I arrived at Penn, because we were not treated like students; we were treated as grown-up artists,” he explains. “We were each given a private studio, and every Monday we had seminars.” Major artists, including Derek Smith, Robert Motherwell, Frank Stella, and Piero Dorazio taught the sessions. Students were able to get honest feedback and ask challenging questions of such giants as Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Gunther Uecker, pioneers of ZERO, the neo-avant-garde movement, which had an exhibition at the ICA in 1965.

Bhavsar recalls a conversation with Mack, who was presenting an idea about creating a glass sculpture in the desert. “I ended up asking him, ‘Have you been to this desert?’ He said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘How dare you put such a little, little thing into such a vast desert without even having been there? Do you know what the desert is like?’” This kind of dialogue, he says, was just one of many candid exchanges the students had with visiting teachers—who were treated as their colleagues.

“We don’t just go to school to get degrees, you know?” he told a New York Times reporter in 2015. “We go to prepare our maturity. I’m a strong believer in individualism. Traditions sometimes put you in a box. An education, whether it’s at a university or kindergarten, has to prepare you to get out of that box.”

Over the years, Bhavsar has received support from the Rockefeller Foundation (which launched him into the New York art scene), a Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, and the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation Grant Award in 2010, given for his contribution to the arts.

“My life is still largely focused on my art,” says Bhavsar, who lives with his wife, photographer Janet Brosious, in New York, empty-nesting after raising twin sons. But they also travel extensively through Europe and India—where, this past November, he had his first show in the country of his birth.

Recently, because of his health, he has eased his pace. “But in my mind,” he adds, “I have not slowed down at all.”

His reason for continuing is simple and yet profound.

“When I present my art, my hope is that people find joy in it,” he says. “It’s like, when you are listening to music, you feel an internal joy overwhelming you to saturation. Even if you are sitting, you are dancing inside. And I find that that kind of reverberation—that’s the ultimate … what do you call it?”

We suggest euphoria. —NP