Savoring the delicacy of first-and-final encounters.

By Steven Schwartzberg | My hosts were right: Bergmannstrasse is a fine choice for solo dining this warm spring evening. I have been in Berlin a few days, inaugurating another month-long trip to Europe. I’m staying with friends of a friend in the relaxed, hip Kreuzberg district, not far from Checkpoint Charlie—the former, grim demarcation between the Western and Soviet segments of this revitalized, thriving city.

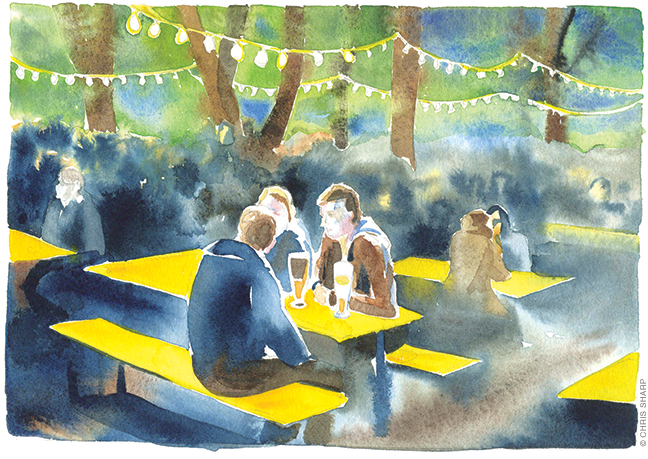

I double-lock my rented bicycle and nab a spot at a sidewalk picnic table of a crowded pan-Asian eatery. Moments later, a young couple sit at the same table. They hear me ask the server about vegetarian options, and quicker than you can say tempeh masala, we’ve plunged into the kind of rapturous, serendipitous evening that is one of my favorite travel delicacies.

They are visitors, too. They’ve just met, at a week-long shiatsu massage training that’s brought them to Berlin. From the looks of it, they’re several days into a brief, casual romance. She is a Swiss “healer” with a radiant smile, gushing enthusiasm about a mish-mash of New Age treatments—reiki, tarot, aura-cleansing, ayahuasca, chakra-something-or-other. He seems far more conventional in comparison: a serious, thoughtful nurse from a small German town. Their English, like that of most young Europeans I meet, is excellent. (With Germanic precision he asks me the English word for male nurse; I’ve never thought about it before, and take pleasure offering what I presume to be the correct answer: nurse.)

This is not an unusual encounter for me. For the last 13 years I have lived by choice without a home: a wanderer, a nomad, an intentional itinerant. I travel often, much of it abroad, typically alone. Meetings of this sort occur routinely enough that I can almost take them for granted.

But for them, our meeting is a novelty. They are not so used to traveling. They’ve never before had a long conversation with an American, much less a middle-aged man who chooses to live on the road. They’re filled with questions about my life, my travels, my experiences. Where have I been? What are my favorite places? How do I decide where to go?

Because they strike me as smart and earnest, because they’re likeable and open-minded, because it’s a glorious night and we are enjoying our second and then third rounds of beer, because I bloom when in the bask of people still young enough to regard the radiance of their cheeks and minds with oblivious nonchalance—because of all this, I respond in ways designed to keep the conversation alive.

We’ve moved beyond appetizers and await our main course. We’ve congealed into one dining unit. The Swiss woman asks me to share a particularly memorable travel experience. I reflect for a moment, waiting for whatever suitable memory bubbles to the surface. Whenever possible, I try not to answer such questions by rote.

This is what rises.

One afternoon, seven years earlier in Thiruvannamalai, India, I found myself walking through an empty patch of land in the middle of an urban block. The building that once presumably stood there was long gone. The plot was now thick with weeds, overgrown bushes, and rubbish. Narrow makeshift dirt pathways served as informal shortcuts from one city block to another.

Crossing through this snatch of urban jungle, I chanced upon an older woman, I’d guess in her late 70s or early 80s, coming the other way, towards me.

On first glance, we were both startled to see each other; I’d crossed this lot a half dozen times and never seen anyone before. After a moment’s hesitation we smiled, and the smile turned to a gentle laugh. Then the laugh deepened and expanded, launching into its own orbit, propelled by its own delight. Soon we were laughing so hard we held our bellies. Our eyes filled with tears. We looked at each other, and whenever our eyes locked it fueled a new surge of laughter.

It finally wound down, having spent itself out. We stayed briefly in silence for a moment and then bowed to one another, deeply, the gesture of namaste. We did not exchange words. We offered no names. We indulged no “Hey wasn’t that sooo cool!” diminishment of what we had just shared; I wouldn’t even have known what language to test. Instead, she continued on her way and I on mine, down the makeshift paths that led to wherever we were heading next. I didn’t look back, yet somehow I was sure she didn’t, either.

It was an unexpected intimacy, and I was flooded with the sense, I know this woman, this stranger. Or I have known her before. Maybe lifetimes before. Maybe we agreed in the 16th century to have only this one brief meeting this go-around, this one encounter of chance, of delight, of love—wordless, fleeting, incidental.

Or not; I don’t know. But maybe it’s as good an explanation as any.

Namaste. In the West, the word has become a breezy staple of the yoga-practicing, Buddha-in-the-garden, prayer-flags-on-the-porch set. In much of India, it is the standard Hindi greeting, but with much deeper resonances than Hi, What’s up? or Yo, Dude.

Namaste: the divine in me sees and acknowledges the divine in you .

By now we are well into our main courses. Another round of beers, more questions, more stories. We take turns speaking and listening. They are getting to know me, and I them, and they each other. Our words touch an honesty that we sometimes save, ironically, for trusted strangers. Night falls.

At a certain point, longer into the evening than any of us anticipated, we decide to part. No—I decide to part. I think they would opt for yet another drink, another story, even another venue, perhaps one with music. But for me it’s getting late and I’m running out of steam.

And suddenly we all know it. We agree to it without speaking. We have decided: This is it. We will not exchange names. We will not enter contact info into our phones and immediately text hey to each other. We will not snap 12 selfies, or one. We are not to meet again.

We hold the silence for a moment, as if cementing and honoring the curious majesty of our unspoken vow. I stand up. We bow a namaste farewell to one another, with gratitude, even (if I dare) with love. I offer a silent blessing for their happiness, look at them, and walk away. Back down the makeshift path of my own life, leaving them to theirs.

For me, the next stop down that path is my rented bicycle, chained to a nearby post. I unlock the heavy chain and release the clever rear-wheel lock that’s a standard feature on Dutch and German bicycles. I’m about to ride away as an overwhelming urge arises to return to the restaurant. This impulse is visceral. I feel the pull in my gut, my belly. Go back! it screams.Say goodbye again, or hello. Offer some small gift. Exchange some keepsake. Get their email addresses, even if you never plan on writing. Or give them yours so the door is not completely shut. Leaving, the impulse suggests, is a terrible mistake.

So strong, this desire to cling even to what is obviously temporary.

But I don’t go back. I know this feeling intimately. The first moments will be the hardest. It’s part of the delicacy, as much as autumn sweetens the end of summer, as withering is part of a bloom. Moving from one encounter, one city, one community, one momentarily beloved connection to the next, over and over—13 years on the road. Life as an intentional nomad is like separation boot camp. It’s one big training in the everyday banality and devastation of good-bye.

I mount the bike. Within a few blocks, the tug in my belly eases, then evaporates in the warm spring air. Before I know it I am once again buoyant: a middle-aged man speeding down the streets of a foreign city on a rented bicycle, ready for the next encounter, the next surprise, the next blessing, the next namaste. I smile as I pedal to the lovely, comfortable home of my temporary hosts.

Steven Schwartzberg C’80 can be reached at Steve_Schwartzberg@yahoo.com.