Mourning Mari.

By Nick Lyons | Mari died last April. The night her last painting exhibition opened she felt excruciating pain in her left thigh, which we felt sure was orthopedic. But when the surgeon operated he found the chewed bone, and then she began the long months of rehabilitation, chemotherapy, radiation.

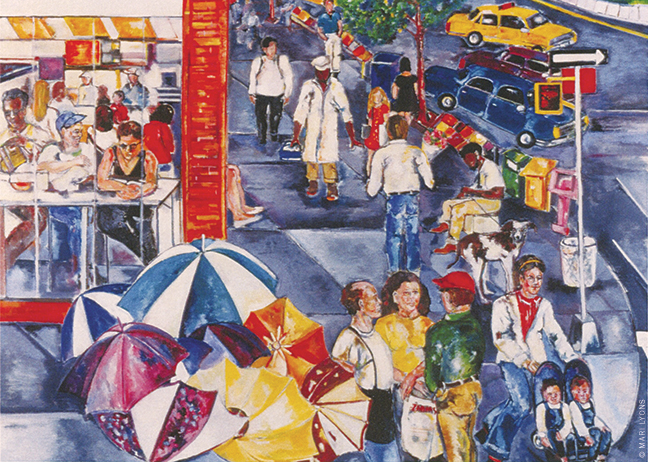

We raised four children together, all into their fifties, some now with children of their own. Mari had painted passionately her entire life, throughout our challenging 58 years: in our bedroom during the hardest years, then in a seedy little walkup room next door, plein air, and finally in large studios on Broadway and in Woodstock. She called herself an “everyday painter,” and her passion for painting never flagged, nor did any of the passions I found in my early twenties. We were crazy about each other and about our children and about making something that would last; we expected to go on and on like that, to continue the dialogue we had started so many years earlier, a kind of duet or dance, stroked by the touch of a hand at the other’s neck in the morning, still half asleep, by hands held as we walked into our eighties, by chatter continuous, without endings.

This is not unusual. Others have been so close. Others by their eighties have lost classmates, parents, siblings, friends, perhaps a spouse. All that lives dies, though like “Everyman” we argue that it comes too soon, that we are not ready. Surely it won’t happen to us. There is no space in our minds for someone close to be not there.

Mari and I could barely spend several hours apart. I can think of only three trips I took, on business, without her in all our years. When she painted in her studio 50 feet from our country home, I went to the window three or four times in an afternoon to snatch a glimpse of her, walking back and forth, brush in hand. That last summer she gave me a wrist watch for my birthday and wrote on the box, “May you always have time. I adore you.”

Months after the operation on her femur, after the rehab and the medication, after a handful of days full of hope, she began to have dizzy spells and an erratic heartbeat. She finally agreed to enter a hospital. She hated hospitals. They were cold and augured the worst, though the worst had never happened. For the first week, spritely when visitors came, she asked, “Why am I here?”

But then the rest of it started, something profoundly sad, inexorable: breath that rarely came without coughing, legs that inchmeal lost their intrepid power, eyes that took on a cast of questioning and fear as one test after another shouted their results, until other functions of the body betrayed her, so embarrassing to that shy woman, as I watched this person I had loved with my heart, whose love had given me heart and purpose and comfort and courage, whose sentences and mine scarcely needed closings, as I watched these things happen to her until, not speaking except for muted whispers, horrible with terror I was hapless to allay, coughing without cease until one morning I held tight to one hand while one of our sons held another, held hoping that something in my life might pass to her, for her life to stay, until her pulse grew erratic, then slow and slower, until there was so little of it and words leapt out. “No. No. No.” And then the pulse ended.

At first I felt nothing. She was gone. She was there, in the raised hospital bed, and not there. I passed my hand over her eyes and they closed and I turned away.

Arrachement. The French word, rough to the ear, conjures the trunk of an old oak, uprooted, leaving a raw hole.

As the hours became days, days months, I tried to crawl upward, starting a catatonic winding down of the life that was no longer a life: closing one studio, turning the other into a storage facility; distributing jewelry to friends and family, clothes to children and grandchildren, giving books from the thousands she treasured to friends who might love to live with them as she had, after libraries said they took too much room and were digitizing. Now and again that first spring I drove to the college where we met and went slowly along the River Road where we first spoke of where our life might go, of our hopes for love, for art, for parenting, for transformation—and how it all in so many ways and far more had taken place.

I thought of where we had started 58 years earlier, of an early fire that had destroyed books and paintings and writings—and of how we built it all again and again, fuller, more richly. I thought of children and grandchildren. Long days and nights of passion. Trips we had taken, paintings and drawings she had made, books I had written. I found a painting of white roses dated seven years earlier, made after the oncologist had given her white roses, to signal her cancer was gone.

Often in the night I cried out—loud, wordless sounds. She had been my life. Without her there could be no life. I was frozen with loneliness. Everything I touched or looked upon spelled Mari. I found a poem by a friend, a woman whose husband had died.

There is nowhere

you are not, nowhere

you are not not.

Somehow, anyhow, as I waffled through the months, the sense that I was too old, that there was too little life left to start again, somehow it palled less. There was something left. Some part of us persisted in me and that part craved to be here. Somehow, at a summer concert we often attended, Beethoven, Mozart, Schumann sent music back into my veins. Some faint song, “Choose life,” began to grow in me. It cried out in the bleak loneliness of the night. Mari would always be “not here” but also here; no one would take her place but somehow, anyhow, regretting nothing, full to overflowing with memories, that refrain grew. “Choose life.” Somehow, I knew in my bones that only life begets and sustains life.

Nick Lyons W’53 is a longtime contributor to the Gazette.