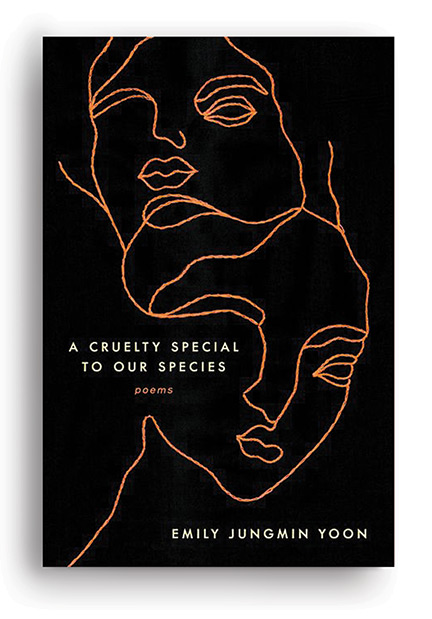

An acclaimed debut collection balances dark themes with delight in language.

A CRUELTY SPECIAL TO OUR SPECIES: Poems

By Emily Jungmin Yoon C’13

Ecco/Harper Collins, 2018, $25.99

Sexual violence against women, the hardships of war, and the persistence of ethnic prejudice are among the themes of Emily Jungmin Yoon C’13’s widely praised poetry collection, A Cruelty Special to Our Species.

The Washington Post called the book “an arresting debut,” while The New York Review of Books noted that “Yoon delicately melds past and present to demonstrate how history, especially that of cruelty, endures.”

The centerpiece of the collection is “Testimonies,” a poetic sequence in the voices of the so-called comfort women. Mostly Korean, many just teenage girls, they were kidnapped or otherwise coerced into institutionalized sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II.

The 27-year-old Yoon, a Canadian citizen born in South Korea who now lives in Chicago, drew the poems from survivors’ oral histories. Hewing closely to their accounts, she infused them with a spare lyricism. “I didn’t change the overarching story,” she says.

“The first night an officer grabbed me/I drank disinfectant/but I didn’t die,” one narrator recounts. “One by one they raped/all night long with filthy wordless bodies/my child’s body,” says another.

It’s strong stuff—especially for an American audience largely unfamiliar with the saga of the comfort women. “I actually feel very scared about it being in the world,” says Yoon, a fourth-year graduate student in Korean literature at the University of Chicago. “Especially since the comfort women issue is such a hot potato, and a lot of people feel very sensitive about it.”

She says the collection is political—“every poem is political,” she insists—but not in a narrow ideological sense. “I would really like the people who read my book to not see this as a Korean nationalist attempt to victimize Korea and vilify Japan,” she says. “It’s much more complicated than just undiscriminating hatred, and I absolutely don’t want people to think that all Koreans hate Japan, or I hate Japan.”

Her concerns instead are more general, involving “the effects of toxic masculinity and war and what humans do to one another: a cruelty special to our species—as human beings, not as members of a certain nation or culture.”

A recipient of the Poetry Foundation’s prestigious Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and numerous other honors, Yoon says she is more at home writing poetry in English than in her native Korean. “All my poetic training has been in English,” she says.

Yoon immigrated with her older sister and her mother to Victoria, Canada, in 2002, when she was 10. Her parents, she says, were seeking an academic environment for them with “more freedom and less stress” than in South Korea. Her father, a dermatologist, remained behind to pursue his profession, and the family visited back and forth. (Her mother, speaking little English, relinquished her dentistry practice.)

From a young age, Yoon wrote both stories and poems, but her high school creative writing teacher’s passion for poetry proved contagious. She applied to Penn in part because of the University’s support for creative writing, and majored in English and Communication. Among her teachers was the poet Greg Djanikian C’71, formerly the director of Penn’s undergraduate creative writing program [“The Moment and the Poem,” Sep|Oct 2014].

Yoon began researching the history of the comfort women as an MFA student at New York University. “I think the poet’s work should be separated from the historian’s work,” she says. “So I was thinking about what I can do to help people access this information through emotion. That’s what I thought I could do as a poet.”

As a child in Busan, South Korea, she says, “I was exposed to the stories of the comfort women early on.” A 2015 agreement between the governments of Japan and South Korea, providing for reparations and an apology from Japan, was supposed to end their conflict on the subject. But the pact failed to represent or satisfy the few surviving women or their supporters, who continue weekly protests at the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

“It’s still an ongoing issue,” says Yoon, not just part of the Korean “collective memory.” In her poem “Notes,” she channels a comfort woman unhappy with the agreement, writing, “Why are you trying to kill/ us twice? Did you exclude us because we’re uneducated, too old?”

No one in her family was a comfort woman, Yoon says. Still, the issue is personal. She recalls her maternal grandmother talking about threats of sexual violence from American soldiers and others during the Korean War.

“There were many days when she would dress up as a boy because there were rumors and fears that young girls were getting raped by the soldiers, American and otherwise,” says Yoon. One of her series of short prose poems—all titled “An Ordinary Misfortune”—references those fears. (Along with “Testimonies,” the prose poems were collected in a 2017 chapbook, Ordinary Misfortunes, published by Tupelo Press.)

A Cruelty Special to Our Species also treats Yoon’s own struggles as an immigrant trying to adapt and blend in. It evinces her fascination with dreams, as well as language, translation, and cultural difference. In the ironically titled “American Dream,” inspired by her mother’s fears “of losing me to a foreigner,”the poem’s narrator is raped in a nightmare by a Korean man while sleeping beside her (white) American boyfriend. “I actually did have a nightmare about that,” Yoon says.

The poet’s delight in language is a counterpoise to the book’s darker themes. “Knowing two languages definitely expands my vision,” says Yoon, who says she finds “poetic qualities” in the process of translation from Korean to English.

She sees the many positive reviews her collection has garnered as a testament to the resurgence of poetry in recent years. “I really, really do believe that every single person deep down loves poetry. They just haven’t encountered a lot of good poetry, or they’ve been taught in a way that didn’t feel pertinent to their lives,” she says. “But who doesn’t love linguistic acrobatics? Who doesn’t love good writing?”— Julia M. Klein