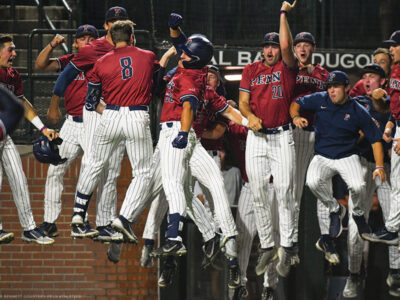

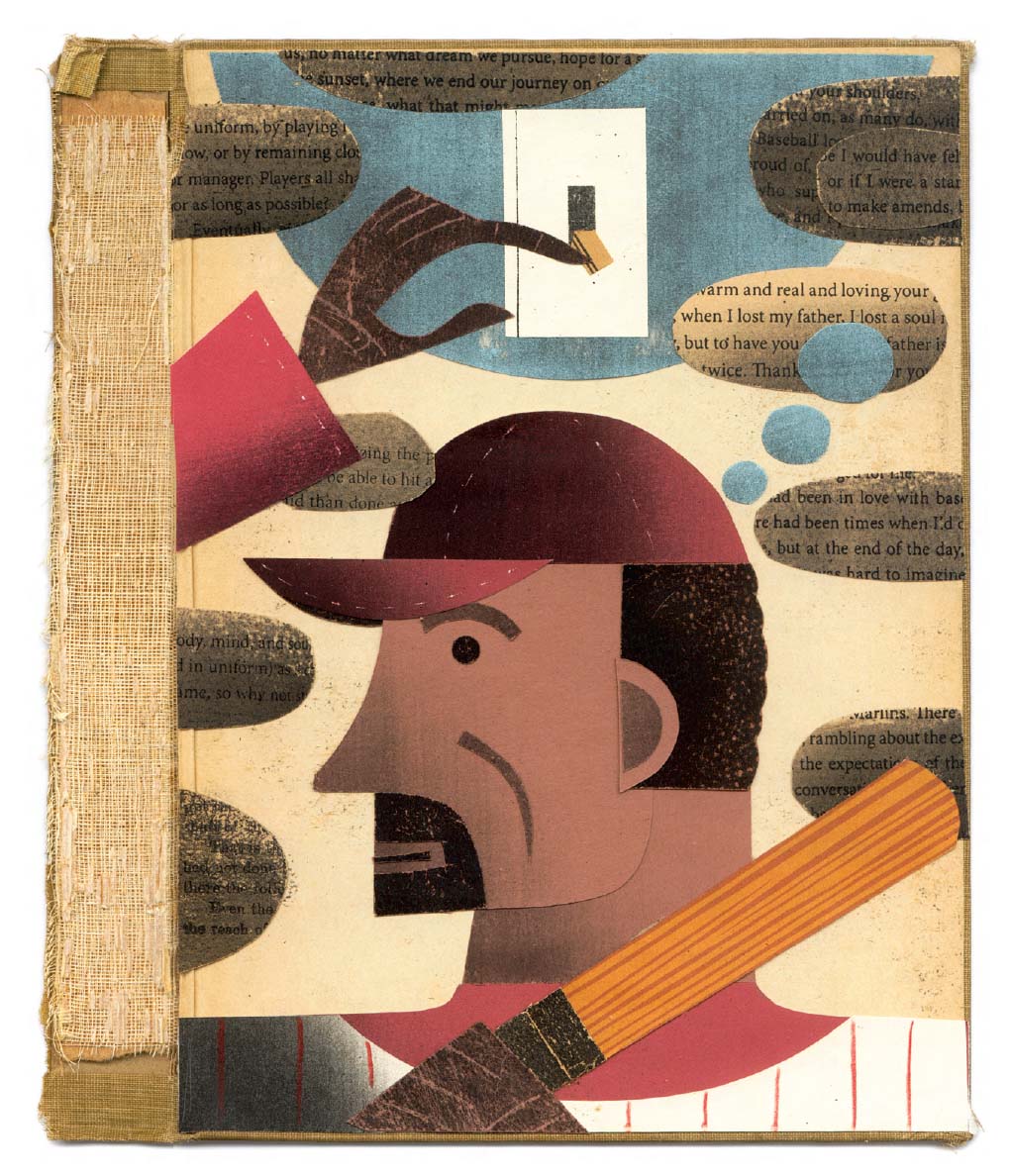

Think it’s easy to turn off your mind when you’re playing baseball? Think again, says a former Major Leaguer (and Penn Quaker standout).

By Doug Glanville | Illustration by Rich Lillash

Interview | Between the Lines

Excerpt | Baseball Family Values

When my career was done, not too many people would say my name in the same sentence as Tony Gwynn’s. The quintessential contact hitter, Gwynn finished his Hall of Fame career with more than 3,000 hits and a mind-boggling .338 career batting average. He played so long that by the time he retired in 2002, his son (Tony Gwynn Jr.) was about to start his own big-league career. I, on the other hand, have been out of baseball for five years now, and my son still has a few hurdles to clear before he makes his Major League debut—kindergarten, for starters.

But in 1997, my second season as a Chicago Cub, I was one of the toughest players in the National League when I had no balls and two strikes on me. It was one of the only times when I would be neck and neck with Tony Gwynn in any category, but then again, no one gets a big trophy for being the toughest hitter with a two-strike count. You certainly can’t take it to arbitration.

After that 1997 season, I learned that a good way to get better as a Major League player was to pay close attention to the best. So when I came across an observation by Gwynn that concentration is the ability to be blank at a given moment, I had to stop and digest what I had just read. Blank? You mean you weren’t supposed to hear the hot-dog vendor yelling out “Ketchup or mustard?”

In the cat-and-mouse game between pitcher and hitter, being blank never seemed like much of an option. The game moved with a violently vacillating rhythm, one minute lulling you into a vacation-like relaxation as you spent innings in wait, getting full on sunflower seeds, then hearing your name called to head toward the batter’s box and a world of exploding sliders. Who flipped the switch? Once you finally put two feet into the batter’s box, the last thing that felt natural was to be blank, especially with the rounded equivalent of a 2 x 4 in your hand. The only semblance of blank was when you took a swing and realized you had missed the pitch by a country mile. You then hoped that this miss had served a purpose, setting up the pitcher by letting him think you didn’t have a plan. If, in actuality, you did have a plan, sending a warning shot that you were onto the pitcher, the spoils of the duel were in reach.

With so much at stake in a ballet of two, I knew I was going to be prepared, even preparing right up until that pitcher started his wind-up. Although blanks litter every equation ever written, most were not put there with a purpose and a goal in mind. Yet according to Gwynn, blank was not only purposeful but the key to everything that mattered.

Hearing wisdom like that from a renowned top performer in my profession put a damper on my hopes that my Ivy League engineering approach could read the mind of the pitcher, knowing what he was about to throw through pattern recognition and a top-secret series of calculations. Since my nickname in Chicago was Rocket Scientist, I figured I could live up to the hype year in and year out by baffling unsuspecting pitchers with anticipatory skills that rendered even the fastest of fastballs useless.

But when push came to shove, even I would have gotten away from my nature if I didn’t find a profound tidbit of truth in Gwynn’s assessment. After all, I did find baseball an escape of sorts. It was where I could be blank by turning off my mind—an elusive state for the son of a psychiatrist and a mathematician. Calculations and analysis were my life; yet baseball had always been my escape, my pod of animal instinct, the place where I needed neither explanations nor theories. I could just be blank, if I so chose.

This had worked well as a Little Leaguer, when I was happy to be a minion of my brother’s loving biddings. Rain, snow, or sleet I was outside playing with big Ken to master the art of throwing a wiffle-ball slider or the Tony Campbell screwball. To buck conventional technology even further, I showed up in my first Little League season as a member of Joey’s Children’s Wear carrying not the then-prevalent aluminum bat but a wooden one, part of Ken’s master plan to create a Major League environment from jump. I guess he knew what he was doing.

Minds were simpler back then and with each passing year, blankbecame less and less of a possibility. I was clouded in high school with crushes on Christine Saunders—or what the scouts were going to write. I was clouded in college by the need to keep grades up in my Systems classes or by wondering whether going to the Olympic trials was a good career move. I was clouded by long bus rides from home and jealous yet innocent hearts in the minor leagues. I was clouded as a big-leaguer by the weight of being productive—and some more important personal issues, which I’ll get to in a minute.

But with the right training, with the right state of being, blank can be found again in an instant. It happens with the euphoria of doing what you love to do, the knowledge that big brother would be proud, that bragging rights would abound for beating up fellow New Jerseyan and New York Met Al Leiter in yet another mano a mano exchange, or it could just happen because of the silence that emanated from Montreal’s Stade Olympique and the Expos’ dwindling, dispirited fan base.

The training was nothing special, really. At Penn I ignored the suggestion of my teammate Anthony Feld W’92 to perform eye drills at home before a game. He would tie a string to a doorknob and use it to create a sight line. I was impressed by his diligence, yet as an engineer, shockingly, I thought it to be mechanizing a natural state. It was then I realized that I went to baseball to be blank, more than anything else.

One year I did employ some eye-switching techniques to avoid focusing for too long on the pitcher or his arm slot. There is a lot of staring in baseball, a necessary lack of etiquette to hone in on the opposing pitcher or the catcher’s glove. After a thousand games of these hyper-focused moments, you have long gotten tired of staring. Gone was the seductive allure of the hitter-pitcher mini-game that had beckoned our eyeballs. We were now looking at sex appeal past its prime. To keep it fresh and to endure another contest to find out whether pitcher or hitter would blink first, we needed to find a momentary diversion. We moved our eyes for a split second, an act that would reset our thoughts and refresh our focus, and in those breaks, we found our lost concentration.

I put all those techniques together in 1999 when, as the centerfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies, I sliced and diced my way through the National League with 204 hits. It got to the point where I could almost project when I would get a hit. I was a first-round draft pick, and I was on my way. The curve would just keep going up. More hits, fun year in and year out, bigger paydays. This game is easy!

Ease crashed and burned in 2000 when my father became ill. As with many a player, life off the field can reign supreme and make blank not only irrelevant but impossible. For the next three years, he would be battling cancer, diabetes, and strokes. Yet strangely enough, that wasn’t the hardest part about finding a peaceful space for concentration. That part came when my manager, Terry Francona, tried to protect me.

My father’s big stroke came on the last day of the 2000 spring-training season. We were in Seattle, about to start the year in Arizona against an ungodly long-armed pitching machine named Randy Johnson. My Mom had relayed the news about my father to me; my first thought was to head home and miss some of the beginning of the season. She assured me that the best approach was to play until our day off the following week, when we would be home in Philly and a short drive from my parents’ home in Teaneck, New Jersey. Momma knows best.

But what was missing from consideration was how I was going to perform with that question-mark-like noose around my neck for the rest of that week. How sick was he? the noose asked. Did he lose function on one side of his body? Would he recognize me?

Those questions tugged at me after I accepted the plan to play out that week. Now I had to start it off against rocket-armed Randy Johnson. Can I be blank now? Please?

All blankness was lost when, in another game in that opening series, I forgot how many outs there were in the inning. When I caught a fly ball, I thought I had recorded the final out, so I strolled in from centerfield—as the Diamondbacks’ Steve Finley not only tagged up from second base to third but now, due to my mistake, kept on going. He scored what amounted to the deciding run in their victory.

Before I even made it into the heart of the locker room, I found my friend, the late third-base coach John Vukovich, whose gruff exterior belied the fact that he was a father figure for many of us when we were miles from home. He hugged my teary-eyed soul and helped me find a moment of peace. Then I faced the music.

The press had some questions. But the shock of it was that they weren’t asking what I expected. They didn’t ask about what happened, or how an Ivy League engineering student had suddenly forgotten how to count. They asked about my father.

How did they know?

Because my manager had told them.

To this day, I love Terry Francona, now manager of the Boston Red Sox. He was my favorite manager, and under his style, I performed at my best. We never had harsh words or issues between us. I played hard; he respected that; end of story. But on this day, he had stepped in to protect me from a barrage of questions that would have been insensitive had the questioners known more about what I was dealing with the last few days. He wanted me to have a reason, teed up and clear. So now I had one, and since I wasn’t the one providing it, I would not come off as giving excuses and ducking responsibility for helping the D-Backs beat us.

Yet the byproduct of that compassion was that I no longer had a zone of blankness to which I could retreat and find peace. I would have to navigate the question of How is your Dad? for what seemed like an eternity. That question would come from anyone who picked up a paper that next day, including those on my team that I hadn’t planned to tell.

Intellectually, I knew that both my manager’s tipping off the press and the response from teammates and public came mostly out of genuine concern and sympathy. But that didn’t make it any less overwhelming. My one escape from fielding the midnight calls from the ER or from my Mom’s shrouded motherly protection was suddenly gone. Baseball had been compromised. I couldn’t leave my baggage in the locker room anymore and just play.

But I came to understand that this was just as much about maturity as it was about someone telling your secret. It certainly was not a concoction of a malicious manager out to get me; quite the converse. As with every other part of my game, I had to evolve, expand my skills, adapt to new rules or rising rookies trying to take my job, maybe even to a more tuned-in Internet. Being blank was harder every day, so I had to get harder every day, in some way. Where did the innocence go? I suppose it went where it always goes, to life.

My father would pass away on the last game of the 2002 season at 7:15 pm, which marked the time of the end of the same game where I recorded my 1,000th career hit. That day I found what blank is all about. I sensed my father’s time was coming soon, and I knew that my desire to return to the Phillies as an off-season free agent was lukewarm at best after losing my starting job. So if I wanted to get my 1,000th hit in the uniform of my childhood favorite team, the time was now. I could only hope that my father spiritually knew when I got that hit.

My opponent—the Florida Marlins’ Carl Pavano—had no chance. It was not me in that batter’s box. It was something bigger. It was a true spiritual moment where my body was just a conduit to a soul. There was no doubt; there was no fear; there was nothing past the moment, nothing before the moment; it was utter and complete concentration, total focus. I knew what was coming; I knew what was going to happen, and I couldn’t stop it if I wanted to do so. Three hits that day gave me 1,001 hits on my career, and the ball that I would bury my father with for where he was going next.

I had finally found what it means to be truly blank.Doug Glanville EAS’93 is an analyst for ESPN.com and the author of The Game From Where I Stand: A Ballplayer’s Inside View, published in May by Times Books.

INTERVIEW

Between the Lines

Whether or not Doug Glanville EAS’93 is the most accomplished baseball player ever to hang a University of Pennsylvania diploma on his wall is something for horsehide historians to decide. While it’s fair to say that Mark DeRosa W’97 and Roy Thomas W1894 would give him a good run for his money, Glanville’s nine-year big-league career with the Phillies, Cubs, and Rangers was more than respectable, and his standout 1999 season—when he hit .325 and tracked down innumerable drives to the distant precincts of the outfield—was the stuff of stardom.

But in the rarified realm of Penn-graduated player-chroniclers, Glanville is in a league of his own. That is not damning with faint praise. In the five years since he hung up his cleats, Glanville has authored an online column (“Heading Home”) for The New York Times, become an analyst for ESPN.com, and, with no help from a ghostwriter, written a book that draws from his Times columns and takes his game to another level.

The Game From Where I Stand: A Ballplayer’s Inside View, published in May by Times Books, is not just a riveting read; it’s also a thoughtful and articulate examination of the game and the sometimes-fragile humans who play it. He covers such explosive issues as steroid use with a clubhouse insider’s insight and a bioethicist’s nuance, while also elevating a juicy story about the perils of bringing a girlfriend into the team’s family room [see excerpt on p. 45] to a meditation on boundaries and propriety.

Judging from the reactions of players like Cal Ripken Jr. and Jimmy Rollins—not to mention scribes like George Will and Peter Gammons—Glanville has caught the game and its players right in the webbing. Buzz Bissinger C’76, author of Three Nights in August and no slouch at taut prose himself, calls it “a book of uncommon grace and elegance,” one “filled with insight and a certain kind of poetry in its spare and haunting prose.”

Glanville and the Gazette go back a ways. As the subject of senior editor Samuel Hughes’s first feature article for the magazine in 1991, he was kind enough to let Hughes hang out in his family’s home in Teaneck, New Jersey, on the day that he was drafted by the Cubs in the first round. Seven years later he pried himself away from the good life in Montreal long enough to grant a phone interview that resulted in an Alumni Profile [July|Aug 1998].

This past March, when Glanville was on campus to give a talk at Kelly Writers House, he shared some increasingly hilarious baseball stories with Hughes over a long dinner that culminated in something called a Cha Cha Cha. Somewhere during that time he also agreed to write an essay for the Gazette and answer some email questions.

Didn’t you get the memo that engineering majors can’t write thoughtful, colorful prose?

At Penn, I remember that the knock on systems engineers was that we were “Jack of all trades, master of none,” but that was the glass-half-empty speaking. I always saw it as a comprehensive discipline, fitting for someone who likes to consider many possibilities and who sought understanding in all the factors that go into creating a design. My parents fostered an environment that celebrated knowledge and learning. Part of this process helped me believe that there really were no boxes unless you allow someone else to define you and put you into it. My father was a psychiatrist, but also a poet, a teacher, and a community pillar, and watching him constantly expand and re-invent himself was inspiring. I came to expect it to be part of my life. So why not be a writer?

Who are some of your favorite baseball writers? What did you learn from them?

I loved Jim Brosnan’s The Long Season. It is poetic, insightful, witty, fair, and downright familiar. He also took a path that I am following in some respects. He wrote for Sports Illustrated; then he got a chance to write a book and said “Why not?” Buzz Bissinger is also a wonderful writer on all things, baseball being one of them.

You address the difficulties of players’ post-baseball transitions, including your own, in your Times column and book. Are you at all surprised by the success you’ve had with your writing?

The Times writing came on the heels of a very difficult time for me in the real-estate market, so it was a coming-out party for me after sifting through the economic downturn that hit my business hard. In some ways, that experience helped me focus on my passions and gave me an even greater appreciation for having clarity. I learned a lot about crisis managing and going after what you love. So when you come from such a pure and focused place that is almost spiritual, you already have success in many ways.

It was wonderful to get the tremendously positive feedback, but had I not, it would have still had purpose and quite frankly, would have been therapeutic, if nothing else. What I am surprised at is the speed at which everything changed. One minute I was looking for an agent roaming the streets of New York; the next minute, George Will is sending me a quote for my book.

Were there some clubhouse stories you wanted to tell but for various reasons couldn’t? Did you run stories that might have caused embarrassment past the players involved?

My first draft eclipsed 100,000 words. So a lot ended up on the cutting-room floor. I made it a policy that anything that would have put someone in a difficult spot, I would contact them to make sure I had their side of the story. In the end, players appreciated my approach and in many cases, trusted that I would run with it responsibly. There are many ways to tell a story, just as I can make an emphatic point without using profanity. There is also an extensive legal vetting early on that provides some direction. I remember debating whether to use a player’s name on a few occasions. One was the player that advised me to “never let them see you with a white woman” or the player Buck Showalter was worried about to the point where he called me to find a back-up. But in the end, I am thrilled with the end product and I think it is fair without losing the honesty and edge needed.

Can you share the story about Scott Rolen and the players’ quilt that you told me over dinner?

One year, the players’ wives had a quilt made to auction off for charity. Each player would get a square and had creative liberty to design it how they saw fit. Then, when the quilt was done, we had to autograph our square. I didn’t have a wife so I dragged my feet until someone designed a basic square for me, which made me one of the last to sign. By then, Rolen had been traded to St. Louis. I finally went to sign my square and saw that the quilt was a bunch of red and white squares for the team colors, with the exception of this big black square in the middle. Upon closer inspection, it was Rolen’s square, which was this dark, purple, black, forest-green color scheme depicting an image of himself at the end of a dock over choppy waters and ravens … in full uniform. Everything about it was ominous. Then it registered that he got in the last laugh on the Phillies and I could not stop laughing for about 15 minutes. It was vintage Scott.

Any key memories of your time at Penn, academic, athletic, or otherwise?

Penn was such a rich experience in a tough time, going from a teen to your 20s. I remember a lot of moments, including oversleeping for my Environmental Studies final and sprinting down Locust Walk completely disoriented (I got there 15 minutes late). I remember a big play I made in a game against Navy where I threw a runner out at home after I had slipped on my first step. I recovered and made the throw of my life. I also remember making the NCAA tournament and knocking off the Big 10 Champ—University of Illinois. People were shocked, but we had five guys drafted from that team. We were really good. We also blew the biggest lead in NCAA tournament history, up 14 or 15 to 0. That was the quietest bus ride home I have ever been on.

Certain Penn connections have stayed with you—David Montgomery C’68 WG’70 and Alan Schwarz C’90 come to mind immediately. Thoughts?

Penn is great at staying connected. Everywhere I played, there was a Penn group at the game. It really has this sense of community that continues on. It is one of the best attributes of the Penn experience. I saw David recently and sat in the owner’s box for a game. Wonderful person and great citizen of Philadelphia. Alan helped me get the New York Times column after many years of our shared growth while I was playing. I serve on the board for the engineering school, which keeps me close to what is happening.

As we speak, The Game From Where I Stand is a few days away from publication. What’s been the reaction from former players who have read it?

Well, Jimmy Rollins was rolling on the floor laughing at various times, which is a good sign. Cal Ripken Jr. was very positive. I think that is what may be most different about this book. Historically (Ball Four, for example), players didn’t take too kindly to this type of exposure, but I believe players will really enjoy my book and feel it is their intimate thoughts expressed in a way where they feel courageous, not betrayed.

When you watch a game now, how do your reactions/impressions/emotions compare with those you had before you turned pro?

It is very different. I still love baseball, but I have seen its ugly side to go with its glorious side. Business, getting traded, released, injured, and booed. Nevertheless, it is such a great game, but I am not that 10-year-old obsessed kid who could not get enough of it. I have a family of my own now, with new joys and new focuses, and I hope that when my kids get older, they will celebrate the game. Maybe then, I will become 10 again.

Do you miss the game enough that you would ever consider going back and becoming a coach or working in the front office of a team?

I would never say never, but I don’t think the rhythm of being involved every day, home and the road, is good for me and my family at this time. I always think about working for and with David Montgomery. I just don’t know how, being in Chicago. I was thinking about turning my book into a mentoring guide and then using it to work with the players—The Game from Where I Stand – Teacher’s Edition!

What’s next?

I would love to help players transition from the game on a big scale. I believe that will be valuable not just to baseball players but anyone transitioning. People in general have a tough time transitioning. When I wrote the piece “The Forgotten” for the Times, I heard from so many professionals outside of baseball who said, “That is my story!” I never received so many 6-7-paragraph emails than I did after that article—from ballet dancers to physicians. It really resonated.

EXCERPT

Baseball Family Values

In the following passage from The Game From Where I Stand, Doug Glanville examines the unwritten code of conduct that guides the “family room”—an Undisclosed Location inside every baseball stadium where the players’ relatives and significant others can congregate.

Once an outsider gains admittance, a Queen Bee sets the standard for behavior. She is usually the wife of a senior player. Mess with the Queen Bee, and you’ll get stung, especially if you’re a rookie.

My introduction to this phenomenon came during my first year in Chicago. I had a guest at the game and hadn’t made clear where she should wait for me after the game. I just left the tickets and figured that I would run into her near the team parking lot. She ended up in the family room, probably by following the crowd around her, as she was sitting in the VIP section with the guests of other players.

After the game, I strolled toward the family room. When I got there, our Queen Bee, Margaret Sandberg (wife of [Cubs second-baseman] Ryne), stopped me at the door and began her interrogation. Was that woman inside the room my guest? I was speechless and must have had a quizzical look on my face because I genuinely could not see past her. In fact, I am not even sure I had ever been in the family room at that point. I had no wife, and my parents were back in New Jersey. Peeking inside, I immediately understood the problem with bringing “random” people into the family room. My date was wearing a skin-tight white body suit with PRECIOUS stenciled across the front written over a set of red lips—a fashion ensemble that understandably made a lot of people in that room uncomfortable.

Since I was a rookie player who was single and free-flowing, I could not fathom the importance of protecting the nuclear family as the Queen Bee needed to do, but I understand it now as a father and a husband. Girlfriends could be interacting with your children in an intimate setting, and you would certainly want to screen them. You also have to be sure these girlfriends aren’t opportunists and wearing skintight bunny suits for everyone else’s husband. Even as a young prospect, I immediately understood that I needed to promise Mrs. Sandberg that I’d be a little more careful in the future.

Precious’s onetime fashion faux pas was nothing compared to the constant havoc created by the girlfriend of my Phillies teammate Mike Lieberthal, whom I’ll call Rita. From the first day she strode into our world, Rita refused to learn the rules of the room. She came in firing from the hip, daring anyone to keep her out. And each time thereafter she seemed to be making a conscious effort to surpass her personal worst. On one occasion, she entered the room wearing pants that were, in the words of my schoolteacher mother, “transparent.”

It’s not pretty when a girlfriend, especially one who has broken so many rules like Rita, manages to get more privileges than a player’s wife. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, security went up ten-fold. A player and anyone in his circle had to get a special ID to go to the family room or any other restricted area. Girlfriends were also allowed to get this identification. Somehow, the rebellious Rita was able to secure her ID well before everyone else. She then flaunted that fact to the wives, one of whom had been denied admittance to the family room because she hadn’t yet received her credentials. (She had to wait in the stands while pregnant.) The fallout was dramatic; the issue made it all the way down to the players at batting practice.

The single player with a Precious or a Rita on his arm must navigate dangerous waters. You don’t want to sell out your girlfriend. But at the same time you don’t want to upset your teammates, who are going to hear it if you bring a snake into their pre- and postgame Eden …

Before Rita was out of the circle, her repeated antics actually caused teammates to caucus before several games to figure out how to approach Lieberthal. Nothing transpired of substance other than to keep whispering in Mike’s ear that there were other fish in the sea. But just reaching that level is like DEFCON 5 for a baseball team.

From The Game From Where I Stand: A Ballplayer’s Inside View, by Doug Glanville. Reprinted by arrangement with Times Books, a division of Henry Holt and Company. Copyright 2010 by Doug Glanville.