Climate change is an inconvenient truth for President Donald Trump. He and other Republicans have called climate change—whose fundamental reality is a matter of near-unanimous agreement among scientists—a “hoax” perpetrated by foreign antagonists or liberal elites.

Citizens who support action to minimize humanity’s contributions to climate change have found cause for further concern in Trump’s picks to lead the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the Department of the Interior (among other agencies), each of whom has amassed a record of climate-change denial and/or opposition to legislation aimed at curtailing greenhouse-gas pollution. Although each of these nominees publicly rejected the notion that climate-change is a hoax during their Senate confirmation hearings, some scientists nonetheless fear that the Trump administration may destroy or impair access to decades’ worth of weather-related data gathered by federal agencies, which would make it difficult or impossible for researchers to continue their work.

These fears were amplified during the first week of Trump’s tenure, when Reuters reported that the administration had ordered EPA officials to remove the agency’s climate change webpage, including “detailed data on emissions.”

Soon after the election, the University had already assumed a leadership role in an effort to preserve such data.

Bethany Wiggin, founding director of the Penn Program for Environmental Humanities, and other scientists created Data Refuge, a new online home for climate change data (DataRefuge.org). In December and January, marathon archiving sessions were held at Penn, as well as in Toronto, Chicago, Indianapolis, and Los Angeles.

“We want the facts to remain accessible to research communities that rely on them,” Wiggin said, “and make sure that, as a country, we are climate-ready.”

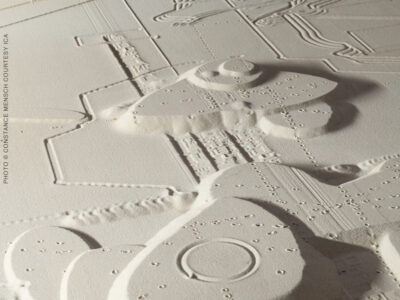

The events aimed to duplicate as much federal data as possible, targeting information housed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Department of Energy, and other federal agencies. Given the data’s vastness, and the diversity of computer formats it takes, that meant heavy coding work. At Penn, it was tackled by more than 250 environmental, behavioral, anthropological, and computer science professors and students, who hailed from locations as nearby as Penn and Drexel, and as far as Toronto and California. They got through 3,692 NOAA websites, and focused on gleaning “uncrawlable” data—information stored in formats that cannot be reached by automated web-crawling archiving tools, such as the EPA’s interactive map of greenhouse-gas emissions.

“My main surprise was how incredibly data-rich the government websites are,” Michael Hucka wrote in an email after he returned to Caltech, where he is a staff scientist in the Department of Computing and Mathematical Sciences. “There is a wealth of interesting information there. I have newfound respect for things that government researchers do on everyone’s behalf and that most people aren’t even aware of.”

Yet if public awareness of this data is so limited, one might ask, why is the country spending money to collect and store it? Budget-conscious advocates of limited government object to a long list of what they consider to be wasteful spending projects at the EPA and other federal agencies.

“You may question the need for NOAA, but you don’t question the need for a daily weather forecast,” said Robert Cheetham MLA’96, who addressed that concern at the Penn event. “You don’t question the need to know as much as possible about where hurricanes will come ashore. That data can’t be handled on a state level, or by private enterprise. We need the federal government to do those things. There are constructive uses for that data that affect our daily lives.”

Curtailing crime is one of them. Law-and-order politicians might take a shine to HunchLab, a predictive policing software created by Cheetham’s Philadelphia-based company, Azavea. Used by police departments in Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis, and elsewhere, HunchLab facilitates the strategic deployment of limited law-enforcement resources by forecasting crime patterns. HunchLab depends on federal, state, and local data about weather, geographical landmarks, terrain, and a host of other factors.

Individual companies don’t have the storage space to house that data, Cheetham contended, adding that privatizing data would also restrict access to it. Open data creates an innovation ecosystem, one that Cheetham wants preserved no matter who is president. “Let’s not waste a good crisis,” Cheetham said. “But I want the energy to be expended more generally. We need more than a Protect Us From Trump tool. We need to create best practices for preserving open data.”

How to archive the Internet is an ongoing challenge that, because of its complexity, has yet to be answered. Jefferson Bailey, director of the nonprofit Internet Archive, spoke about a congenital defect shared by virtually all websites: impermanence. The average website’s longevity is 100 days, Bailey said. Some websites change constantly, creating a sort of steady erosion of older information. Others disappear because of neglect, meaning that they aren’t clicked on or updated with new content. Link death is what’s behind that familiar “page not found” message when you point your browser to a link that has either changed addresses or vanished entirely.

“[The] reality is that the Internet has no natural custodian,” Bailey said. That’s why Internet Archive held “End Of Term Harvests” in 2008 and 2012. These efforts were not focused solely on climate change data. Instead, they captured a wide range of online material considered vulnerable, including on traffic safety and cancer research.

When word spread in late January that Trump administration officials had threatened federal web pages housing climate data, “Data Refuge, EDGI [Environmental Data Governance Initiative], and Internet Archive worked through the nights,” according to an update on the Data Refuge website, to comb through as many websites as they could. Even before that effort, the project had fed more than 7,000 websites into the Internet Archive, and secured more than 1.5 terabytes of uncrawlable data. (To put it in context: that’s roughly equivalent to the 7 million volumes held by Penn Libraries; printed out as plain text on paper, it would fill more than 160 tractor trailers. Yet the National Climatic Data Center generates approximately that much new data every week.)

And protecting data from permanent deletion doesn’t necessarily safeguard it from other hazards. The duplication of data sets can lead to other problems. Tampering is a big one: the alteration of a data set to cast doubt on formerly reached conclusions. This tactic could sow doubt in the minds of legislators and the public—as its use by the tobacco industry in an earlier era attests.

“Everyone wants science to be on their side,” said Michael Halpern, deputy director of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “When it isn’t, there’s a tendency to suppress, distort, or manipulate whatever information is inconvenient to the policies that people want to put forward.”

There is historical precedent for their concern. During his nine-year term as prime minister of Canada, Stephen Harper ordered the destruction of printed scientific research and data, shuttered world-class ocean and environmental research libraries, and instituted rules that prevented government scientists from speaking to reporters.

Michelle Murphy, who calls this libra-cide, organized the first Data Refuge event, held at the University of Toronto. “We need to have hard conversations about what’s going to happen if the state pulls back from its obligation to monitor and regulate the environment and the climate,” she said.

The harder conversation may be with the American public. Raising enthusiasm for open scientific data is no easy task, Wiggin conceded. “Without simplifying, we need to be really clear about what the issues are. Why is open data important? Who does it impact? What happens when data disappears? Can it be salvaged?”

The answer to that last question is no. At present, there’s no app for that.