The art of Spiegelman.

“In effect, everything I learned comes from comic books,” Art Spiegelman told a packed and enthusiastic crowd at Irvine Auditorium. “I learned how to read from Batman; I learned about sex from Betty and Veronica, feminism from Little Lulu, economics from Donald Duck, religion from Peanuts, politics from Pogo, and everything else from MAD Magazine. As a result, I should have been prepared when aliens took over our government.”

By “aliens,” Spiegelman—artist, essayist, graphic novelist, and creator of the 1992 Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus: A Survivor’s Tale—was referring to his latest book, In The Shadow of No Towers, the subject of which is the September 11 terrorist attack and the Bush administration’s response to it.

Spiegelman—dubbed “Penn’s Honorary Dean of Comic Art” by Dr. Wendy Steiner, the Fisher Professor of English and founding director of the Penn Humanities Forum—presented “Comix 101” in September, an appropriate opening event for the forum’s Word & Image series this academic year. His lecture, an entertaining lesson on the art and evolution of comics, was filled with many comic-strip visuals—both his own and those of his predecessors and contemporaries. The spelling of Comix 101 was an intentional tip of his hat to the underground comic artists of the 1960s who spelled the word that way.

“Some time ago, people figured out that the comics are some kind of art,” Spiegelman said. “Comics manage to function the way your brain functions, in that comics are short bursts of language and iconic pictures. That’s really how one thinks—one doesn’t think in long paragraphs, one doesn’t think in holograms.”

Spiegelman, former editor of two magazines devoted to the art of comics (Arcade: The Comics Revue and RAW, the latter co-founded and produced with his wife, Francoise Mouly, art editor of The New Yorker), admitted to looking up the word comics in the dictionary.

“I realized that the American Heritage Dictionary was a very cool dictionary because it uses Nancy (the popular 1930s comic strip by Ernie Bushmiller) for the definition, ‘a narrative series of cartoons.’ Then I wasted some more time and looked up cartoons.”

Ultimately, Spiegelman explained, he came to see comics as “a kind of diagram, a way of communicating a kind of picture-writing that gets expanded out by the cartoonist.”

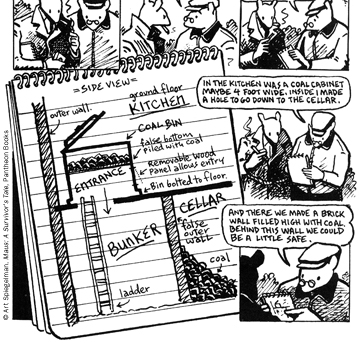

To demonstrate “picture-writing,” Spiegelman selected a page from Maus, the acclaimed graphic novel based on the story, told to him by his father, about his parents’ lives before, during, and after their escape from the Holocaust. The selection depicts Vladek, Spiegelman’s father, drawing in a notebook while explaining to “Artie” how he built a bunker below the kitchen cellar and behind the coal-storage bin. To the left of the two panels depicting father and son, there is a close-up of the spiral notebook with a drawing of a diagram of the bunker.

“I am interviewing my father to get information for my book about his life during the Hitler years,” Spiegelman explained. “And here is the same diagram made dimensional, and then the comic strip begins to move forward in time in the conventional way. So maybe comics are a narrative series of diagrams.” The narrative is the “most interesting” aspect to Spiegelman, “because a narrative is a story … and each page is a kind of architectural structure.”

At age seven, during a trip to the grocery store with his mother, Spiegelman became enchanted with comics when he discovered MAD Magazine. “I studied MAD the way I studied the Talmud,” he recalled. After trying his young hand at creating comics, he came to realize that “if you want to draw someone who is wimpy and meek, you draw them with round shoulders. If you want to draw a thug who is overbearing, you draw them with stubble and a big jaw. If you want to draw an ethnic slur, you draw stereotypes, which is not to say it is benign,” Spiegelman added. “There is power there … you can use comics to demonize.”

On February 15, 1993, just after Spiegelman joined The New Yorker, his first cover for the magazine was published. To commemorate Valentine’s Day, he depicted an Orthodox Jewish man and an African-American woman kissing. It appeared “in the wake” of the Crown Heights riots in Brooklyn, and the “scars” of the racial tensions between Hasidic Jews and African-Americans “were still fresh in New York,” he recalled. “My intention was to represent the two communities as kissing and making up.” It proved to be a bit early for that; the cover sparked protests from both the black and Hasidic communities.

No longer on staff at The New Yorker, Spiegelman continues to write essays and create covers on a freelance basis. His “9/11/01” cover for the magazine’s September 24, 2001 issue may be the one for which he is most remembered. Other than the date, the price, and the magazine title, which are in white type, the cover appears, at first glance, to be completely black. It is not. The two black images of the World Trade Center’s North and South Towers are set against an almost-imperceptibly lighter black background, creating a powerful image.

Spiegelman and his family, residents of lower Manhattan, were witnesses to the horror of 9/11.

“Before 9/11 my traumas were all more or less self-inflicted,” he writes in the introduction to In The Shadow of No Towers, “but out-running the toxic cloud that had moments before been the north tower of the World Trade Center left me reeling on that fault line where World History and Personal History collide—the intersection my parents, Auschwitz survivors, had warned me about when they taught me to always keep my bags packed.”

When he thought about creating a cover for The New Yorker’s first issue post 9/11, he said, “It seemed that one thing that made some sense was this black cover, these ghost images that you can only see as light shifts, and which echoed my walk north two blocks to my studio where I kept turning around to make sure the two towers were still gone.” It was that walk which “ultimately inspired the image” for the cover, and which would be the cover for In The Shadow of No Towers.

After 9/11, Spiegelman tried to make sense of what he had seen that day. “I began to make a series of large single page strips … giant broadsheets just like the ones in comics in America in the beginning of the last century.” These large pages would eventually become the format for his book.

“Disaster is my muse!” writes Spiegelman in the book’s introduction. No surprise, then, that he included his own 9/11 experience and “those images that stuck with me,” as he told his Penn audience. One image was the horrified look on his daughter’s face “when she turned around and saw me and realized that what she saw outside the window was not a hallucination, that she saw bodies falling down—this brought it home.” Another was of the “evanescing bones of the Towers that fell right behind us when we got back on the street outside her school.”

Spiegelman said that he did not intend the book as political cartoon art. Yet as he proceeded, he “found there were hints of political commentary entering my work against my better judgment.” After 9/11, he said, “I wanted to escape that shaky world ground into what I really loved, old comics … I could not listen to music. I could not look at paintings, all were too beautiful.” When he looked back at the old comics, “they began to get channeled into my spirit.”

Perhaps as an homage to his beloved old comics, one-half of In The Shadow of No Towers is “The Comic Supplement,” filled with reproductions of early 20th-century comic strips—Krazy Kat, Hogan’s Alley, Kin-der-Kids, Little Nemo in Slumberland, and Bringing Up Father. Although Spiegelman “channeled” Kin-der-Kids into his book as the Tower Twins, it was Krazy Kat, George Herriman’s Kat-Pupp-Mouse love triangle, that captured him the most: “That strip was as close as I could come to find wisdom in comics after September 11.”

—Barbra Shotel CW’64