Thomas Evans was the trusted friend of royalty and a secret diplomat with an eye for beauty. Such are the rewards of dentistry.

By Samuel Hughes

How well I remember Dr. Evans, who was our family dentist. He had a black beard. Many tales of his “successes” were whispered, perhaps fostered by himself—be that as it may, he was certainly attracted by beauty … It seemed somehow symbolic of the fashionable Second Empire that for the first time in history a dentist had succeeded in achieving an establishment comparable to [that of] a prince. —Baroness Agnes de Stoeckl, When Men Had Time.

It sometimes happens when the crowned heads of Europe wish to communicate with one another without any responsibility they send for Evans to fix their teeth. As you are not likely to send so far for a dentist, I need only add that the messages of this sort, which he bears, are always communicated to him by word of mouth and in the presence of no witnesses. —Letter from John Bigelow, American Consul-General in Paris, to William Seward, U.S. Secretary of State, November 21, 1862.

Some professions, by their very nature, suggest glamour, intrigue, adventure. Dentistry, with all due respect, is not one of them. Which makes the achievements of Dr. Thomas Evans—the West Philadelphia native who funded the dental institute and museum that bears his name (and which merged, after his death, with Penn’s School of Dentistry)—all the more remarkable.

Consider: Having moved from Pennsylvania to Paris in 1847 without even speaking French, he became the dentist of choice and the trusted friend of a glittering array of kings, princes, empresses, grand duchesses, czars, sultans and other potentates. (A visit from Evans, wrote Baroness de Stoeckl, was a “profound honour,” since he chose his patients “as a King chooses his Ministers.”) He became the court-appointed surgeon-dentist and confidant of the Emperor Napoleon III and his wife, the Empress Eugénie, and he probably saved the latter’s life at the fall of the Second Empire when he helped her escape from the Parisian mob to England. (Evans also helped save the life of Germany’s Crown Prince Frederick long enough for him to reign for 99 days as Emperor Frederick III by fashioning a silver tracheotomy cannula for the prince’s cancerous throat, allowing him to breathe.)

Although he spent most of his life in France, and lived in many ways like a Frenchman—Le Gaulois opined that Evans “had a thoroughly Parisian look about him and could inspire our instinctive friendship”—he remained a loyal American citizen. He was largely responsible for convincing Napoleon III not to recognize the Confederacy, thus keeping France firmly on the sidelines of the American Civil War. “I have a feeling that in many ways he saw himself as a successor to Benjamin Franklin, serving as an American in Paris,” says Dr. D. Walter Cohen D’50, former dean of the dental school. “He really was a Renaissance person.” And, like Franklin, he valued both the useful and the ornamental.

Evans was, unquestionably, a highly skilled and innovative dentist—in addition to his deft touch with gold-foil fillings, he was the first to use vulcanite rubber as a base for dentures (turning down a franchise offered him by Charles Goodyear); he also introduced nitrous oxide as an anesthetic to Europe. In a time when teeth were a source of unalloyed misery—and in a country where the dental arts were the province of quacks—his talents were bankable. But the fact that so many important men and women trusted him was due to his reassuring chair-side manner, his engaging conversation—and his discretion. He once described himself as “my patients’ father confessor,” and he liked to say that: “Ears hear, but they as mouth must often close.”

Highly sensitive to human suffering, he introduced a light, ventilated, American-style ambulance and field hospital to the French, which saved many lives during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. (“It is the dream of every French soldier, if he is wounded, to be taken to this ambulance,” wrote Henry Labouchere, Paris correspondent for the London Daily News.) For such contributions he was made a Commander of the Legion of Honor, the first American to enter the ranks of that organization.

Along the way, he became the publisher of the American Register, an English-language newspaper in Paris; organized the American Charitable Association of Paris to aid indigent American citizens; helped found the first American community church in Paris; and gave 100,000 francs to the Lafayette Home for young American women who came to Paris to study art.

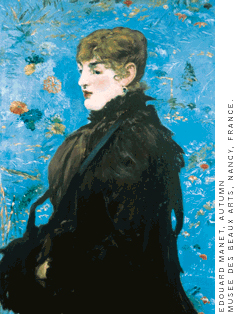

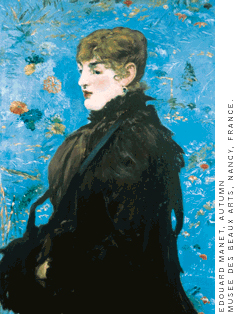

As the Second Empire gave way to the Third Republic, “Handsome Tom” took on a beautiful mistress, Méry Laurent, who inspired so many artists and writers—including Edouard Manet and the poet Stéphane Mallarmé—that one wag appreciatively dubbed her “toute la lyre,” the lyre in question being that of Orpheus. While acquiring mistresses may not rank among life’s loftiest achievements, this one did indirectly lead to an art collection that Le Figaro hyperbolically described as “one of the most important and best collections of paintings which exists.” It included several by Manet himself, three of which would resurface in the dental school’s storage warehouse nearly 80 years after Evans’ death—thus providing the foundation of the school’s current endowment.

A few of the nearly 200 medals, ribbons and other gaudy baubles he received from his royal clients still hang in a glass case at the entrance to the dental-school library. The carriage that Evans used to smuggle Eugénie out of Paris has been rescued from a shed at the New Bolton Center by Dr. James F. Galbally Jr. GD’74, associate dean of the dental school, and taken to the Blérancourt Museum near Paris as a symbol of Franco-American friendship. The Manets are hanging in museums in Boston, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Evans’ letters and papers are in the Department of Special Collections in Van Pelt Library and the dental-school library. The jewels—diamond necklaces, ruby-studded snuffboxes, brooches and rings and stickpins, inventoried at more than $1 million after his death—are in museums and private hands. Other paintings and gifts from royal patients will again be on display when the school’s new Schattner Center opens in 2001. By such remains can we identify the man.

From a very early age, Evans had an unusual sense of destiny. The boy who grew up in a Quaker household near what is now 37th and Chestnut streets saw his name “on a silver plate or perhaps a brass one—Thomas W. Evans, Dentist,” he later wrote. “At night I dreamed of this plate on the door, of people coming to have their teeth filled, new ones made for them … and even in those childish days I thought perhaps I might some day be called Doctor … “

His father tried to steer him toward a career as a lawyer, but finally gave in and let the sure-handed Tom become apprenticed to a silver- and goldsmith named Joseph Warner. There he became adept at manipulating metals; picked the brains of any dentists who came into Warner’s shop; and read whatever books on dentistry he could get his hands on. His first patients were sheep and dogs and cattle, whose teeth he would drill and then fill with a tin-foil amalgam. Later, some trusting two-legged souls allowed him to plug their cavities.

In 1843, having attended lectures at Jefferson Medical College and studied with a leading Philadelphia dentist, he earned a certificate permitting him to practice the “art and mystery of dentistry.” After practicing briefly in Baltimore, he hung out his shingle in Lancaster, Pa., and began making a name for himself with the new technique of gold-foil fillings.

Evans’ motto—”gold, only gold”—was a wise one, says Dr. Milton B. Asbell GD’54 G’81, author of A Century of Dentistry: A History of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine 1878-1978. Gold, he explains, “adhered to all surfaces of the tooth; it didn’t decay; and when you were finished you could polish it and it looked like a piece of jewelry.” Evans didn’t invent the technique—which involves taking paper-thin sheets of gold, rolling them into tiny balls and then hammering them into a cavity, where they coalesce into each other—but his expertise with it brought him his fame and much of his fortune.

In 1847, he won the “First Premium” for his gold-foil fillings at the Franklin Institute’s exhibition of arts and manufacture. The exhibit caught the eye of a Philadelphia physician named John C. Clark, who had retired to Paris and returned for a visit. An American dentist in Paris—Dr. Cyrus Starr Brewster, whose clients included King Louis Philippe and his court—had asked Clark to find him an able young assistant. Clark recommended Evans, and that November the 24-year-old dentist and his wife, Agnes, arrived by steamer in France.

A few months later, the Revolution of 1848 sent Louis Philippe, the “Citizen King,” packing. By the end of that year, Prince Louis Napoleon—Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew—had gone from exiled pretender to president of the French Republic; a coup d’etat in 1851 paved the way for him to become Emperor Napoleon III.

By then he was already a patient of Evans, who had responded to an urgent summons to relieve a howling toothache the year before. Evans, filling in for Brewster (who was either traveling or ill), had handled the prince’s molar with gentle efficiency. As he was leaving, Louis Napoleon said: “You are a young fellow, but clever. I like you.” It was, to borrow from another Paris-loving American, the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Each had a good deal to offer the other. Evans provided relief from frequent agony (the emperor, he wrote, had “extremely delicate teeth” and was “more than usually sensitive to pain”) as well as his agreeable company and keen observations. Louis Napoleon, of course, could offer the enormous prestige of his imperial patronage—not to mention inside information about his plans to rebuild Paris, which enabled Evans to buy up strategically situated real estate and then sell it, at very handsome profits.

The emperor, who was enlightened enough to value talent and character over pedigree, “had an excellent opinion of dentists in general,” wrote Evans, “and saw no reason why they should not be as proud of their specialty as the practitioners of any branch of medicine or surgery.”

It was a good time to be an American dentist, armed with a good knowledge of anatomy and the latest scientific advancements. In the wake of the French Revolution, the profession had regressed to a medieval level, its status discernible from the old French proverb, “To lie like a dentist.”

“Physicians and surgeons considered the care of the teeth as unworthy of their attention and science,” wrote Evans, and as a result, “extractions were left to be performed by mountebanks at street corners, or fakirs at fairs, where the howls of the victims were drowned by the beating of drums, the clash of cymbals and the laughter and applause of the delighted and admiring crowd.” Dentists, he added pointedly, were “expected to enter the house by the back-stairs,” and he admitted that the occasional barb at his profession “sometimes left a sting.” After a few years, Evans’ reputation had reached a level where, if his wealthy patients did not treat him with the respect he thought he and his profession were owed, he politely sent them elsewhere. The effects of that, he noted, were “wonderful.”

When Louis Napoleon began casting about for a wife, he entrusted Evans with the task of sounding out Princess Caroline Stephanie of Sweden while he tended to the royal bicuspids. Evans carried out his mission well—the first of many diplomacies—but in the end Napoleon married the Spanish Countess of Teba, Eugénie-Marie de Montijo de Guzman, in 1853. Evans, who had been filling her cavities, too, was naturally invited to the wedding, and later that year he was formally appointed “Surgeon Dentist to the Emperor,” with a status comparable to that of the court physicians.

When Evans was about to depart for a visit to the United States in 1854, the emperor invited him to the Palace St.-Cloud, receiving him in the empress’s antechamber. He then brought out the five-pointed star of the Legion of Honor, and pinned it on Evans’ jacket.

“We want you to go home a knight,” said Louis Napoleon, at which point Eugénie entered the room, saying that she wanted “to be the first to congratulate the Chevalier.”

“I hope your friends in America,” the emperor added, “will understand how much you are appreciated by us.”

A summer day in 1864. The emperor’s private study at Compiègne. Louis Napoleon is in an unusually somber mood. The American Civil War is going badly again, he reminds Evans; General J.A. Early’s army is advancing on Washington; and he would not be at all surprised to be awakened some day soon by the news that the capital has been captured. He informs Evans that he is being pressured by England to recognize the Confederacy as the only way to bring about the end of the war, and acknowledges that he is strongly considering doing so.

Such a move would be devastating to the Union, and Evans, the only pro-Northern voice to have Louis Napoleon’s ear, knows that he has to make a strong case. The war, he tells the emperor, is “certainly approaching an end”; the resources of the South are almost exhausted; and with nearly a million seasoned soldiers in the field, the military power of the North is “irresistible.” Becoming “warm,” as he later put it, and “quite carried away by my subject,” he pleads for, in his own words, “hands off and to wait a little longer,” since recognizing the Confederacy “would only cause much more blood to flow.”

At that moment a hidden door opens in the wall. The eight-year-old prince imperial, known as Lou-Lou, enters the room. Evans goes for the heart. “For this boy’s sake you cannot act,” he says, putting his arm around Lou-Lou. “He is to succeed you, and the people of my country would visit it upon his head, if you had helped to destroy our great and happy Union.”

Before the emperor has a chance to respond, Evans offers to take the next steamer to the United States and assess the military and political situation for himself, then report back. Louis Napoleon, with a hint of amusement, gives him his blessing and agrees to hold off on a decision until he receives Evans’ report.

In Washington, D.C., the mood is glum, both for the prospects of ending the war and for President Lincoln’s reelection. Evans meets with a “rather gloomy and dispirited” Seward and a guardedly optimistic Lincoln, who according to Evans is “much pleased” with the self-appointed mission. “Well, I guess we shall be able to pull through; it may take some time,” Lincoln concludes. “But we shall succeed, I think.” He and Seward suggest that Evans visit General Ulysses S. Grant, and provide him with a special pass and introductions.

Nightfall at City Point, Va., where the Army of the Potomac is laying siege to Richmond and Petersburg. A large campfire keeps the mosquitoes somewhat at bay. Grant lights a cigar, throws his leg over the arm of his chair and begins to talk.

It is the first of several personal meetings. Grant is frank and open with Evans, allowing him to take notes about his military strategy and discussing his correspondence with General William Tecumseh Sherman, which will lead to the famous march through Georgia. Grant is “very positive about the final result of the war,” writes Evans, who is impressed with the general’s military bearing. Together, they ride toward Richmond, at times drawing near enough to see the Confederate pickets; occasionally a shot whistles over their heads. (Grant will later write to his wife suggesting that they send one of their sons to France to be educated under Evans’ auspices, and after his presidency will be entertained by Evans in Paris.)

Back in Washington, the mood is increasingly optimistic, and Evans concludes that the end of the war is “not far distant.” He writes a letter detailing his observations to Louis Napoleon—who decides not to recognize the Confederacy, after all. The emperor later tells Evans that as soon as he read of Sherman’s proposed plan to cut to the sea through Georgia, he saw by his maps that it was the “beginning of the end.”

Evans was not an entirely modest man, but any suspicions that he might have exaggerated his own influence with Louis Napoleon were, according to Seward, “entirely removed during our civil war … The execution of the trust by the doctor was in all respects moderate and becoming.”

The Grand Prix d’Honneur from the Paris Exposition of 1867: Where is it now? It was awarded to Evans—or, more properly, to the U.S. Sanitary Commission—for his exhibit of hospital tents, railroad hospital cars, surgical instruments and the like. Evans had already seen first-hand the gruesome results of modern warfare during the Crimean War and the French-Italian conflict of 1859, and his visit to Grant’s headquarters allowed him to study a subject close to his heart: “provisions made for the care of the sick and wounded.” That, and the two months he spent in Philadelphia afterwards gathering information about the latest developments in hygiene, led to a book detailing the work of the sanitary commission (a volunteer citizens’ association that supplemented the work of the Army Medical Bureau). It was followed by another book, Sanitary Institutions during the Austro-Prussian-Italian Conflict of 1866. Both would impress important readers in Europe, and would, despite resistance from bureaucracies, lead to changes in the treatment of wounded soldiers.

With the help of Dr. Edward Crane, his friend and literary editor, Evans assembled, at his own expense, the various inventions that had saved tens of thousands of lives during the Civil War, and had them shipped to the Paris Exposition. The Grand Prix d’Honneur was presented by the emperor, and Evans himself received a special prize for his design of a light, well-ventilated “flying ambulance.” One ranking physician from the French Army wrote that the various articles of the exhibition “all bear the stamp of the enlightened patriotism and the importance which the Americans attach to the preservation of human life and the alleviation of the inevitable evils of war.”

When the Exposition ended, Evans quietly stored the materials on land near his own property for possible future use. Three years later, on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War, he would be elected president of the newly formed American International Sanitary Committee. During the grim siege of Paris, the American Ambulance, as the collection was called, would save many lives. By then, Evans would be involved in another, more personal mission of mercy.

The Franco-Prussian War was a bloody, humiliating disaster for France, as Evans knew it would be, and it cost the emperor his crown. Louis Napoleon was taken prisoner by Germany following a disastrous battle at Sedan, and when the news reached Paris, the same people who had been shouting “Vive la guerre!” responded by tearing the Napoleonic eagles off the wrought-iron fences outside the Tuileries and shouting “Down with the Empire!” and “Death to the Spanish Woman!” General Louis Trochu, the military governor of Paris who had pledged to defend Eugénie to the death, locked himself in the Louvre until things quieted down.

It was not a good time to be the empress regent, who knew that her husband was a prisoner of war but did not know whether her 14-year-old Lou-Lou, a soldier in the French Army, was dead or alive. When Eugénie—accompanied by an attendant, Madame Lebreton—finally fled the Tuileries, she turned instinctively to Evans’ mansion, Bella Rosa, on the Avenue de l’Imperatrice.

“The evil days have come,” she told him, “and I am left alone.” Evans did not hesitate to help her, even though he knew that the revolutionaries might well seize his property—or himself—in retaliation.

He began by persuading the exhausted empress to get some sleep and wait until the next morning, when he would take her by carriage, in disguise, to the coastal town of Deauville, where his wife was on holiday. Some members of the palace staff, anticipating the worst, had obtained several travel documents, including a British passport issued to “C.W. Campbell, M.D.” and his patient, “Mrs. Burslem.” Crane became Dr. Campbell; the empress became his patient; Evans would be her brother; and Madame Lebreton, her nurse.

At 5 o’ clock the next morning, Evans, Crane, the empress and Madame Lebreton stepped into his brown, four-seated carriage and set off for the coast. When they passed through the Porte Maillot, Evans casually blocked the view of the empress with his body and a newspaper, and told the sentry that he and his friends were going for a drive in the country.

The journey took about a day and a half, and though it was tiring and uncomfortable—and occasionally unnerving—they made Deauville without serious mishap. Evans spent money liberally on rooms and fresh horses and carriages, and had to think quickly on a number of occasions. In the town of Lisieux, the story goes, a policeman was abusing a man in the street, whereupon Eugénie loudly announced that she was the empress and that the man must be let go. Evans gestured with his finger that the poor woman was off her nut, and the passers-by laughed and went on their way.

At her hotel in Deauville, Agnes Evans was astonished to see her “dear Tom,” who looked faint and “deadly pale with great tears on his cheeks.” He told her: “I have the empress to save—she must be hidden in your room until we can get her out of the country.” He and Crane then found a British sailing yacht and asked the owner, Sir John Burgoyne, if he would take them across the channel to England. Burgoyne first refused, then, at Evans’ and Crane’s urging, put the question to his wife, who shamed him into agreeing.

“It is a great responsibility that you are asking me to assume,” Burgoyne told him. “Perhaps,” Evans replied; “but the greater the responsibility, the greater the honor.”

They almost didn’t make it. A terrific gale blew up, and nearly sank them. (“As the yacht reeled and staggered in the wild seas that swept over her deck and slapped her sides with tremendous force,” Evans wrote later, “it seemed as if she was about to be engulfed, and that the end was indeed near.”) But after a harrowing night, they anchored in Ryde Roads and checked into a hotel, whereupon Evans discovered from a newspaper that the prince imperial was in Hastings, a short distance away. Evans then engineered the reunion, which must have been almost as touching as his rather ripe prose suggests: “The tears of joy flowed abundantly, and her lips murmured words of thanks to Heaven … “

The emperor, released by Prussia the following year, joined Eugénie at the mansion near London that Evans had helped her find. He died there two years later. Lou-Lou was killed in 1879 by Zulu warriors during a guerrilla war in South Africa. The only one who could identify the decomposed and mutilated body was Evans, who knew where the gold-foil fillings would be. The empress lived sadly on for many years, occasionally visited by Evans, who wrote The Fall of the Second French Empire: Fragments of My Memoirs to refute the “calumnies” that had been written about the imperial couple. Even his enemies would concede that he had remained loyal to the Second Empire, long after there was anything in it for him. But he adapted pretty well to the Third Republic, too.

She was tall, with an exquisite tea-rose complexion, blue eyes, and fair hair with hints of red, a laughing beauty with arched eyebrows and a wide-eyed gaze that gave her a bewitching expression of surprise. Her mouth was sensual, her bosom formidable, and she excited artists, especially Manet … —Gerald Carson, The Dentist and the Empress.

One night in the spring of 1872, a beautiful actress named Marie Laurent appeared in an operetta titled Le Roi Carotte. After the performance, a basket brimming with white roses was handed to her with the card of Thomas W. Evans, Dentist.

“He carried her off into the warm April night in a handsome carriage,” wrote Carson, “he a whiskered fiftyish gentleman with courtly manners, to see a show and later sip champagne in a caberet.” The next year, at the Chatelet theater, “the dancers parted, and Marie made her spectacular nude leap out of the silver shell.”

Her name was later anglicized to Méry, and she enjoyed a “stable, orderly, almost bourgeois relationship” with Evans that lasted for a quarter of a century, despite the presence of the devoted Mrs. Evans at Bella Rosa. He gave her a monthly allowance of 5,000 francs, later raised it to 10,000, and provided her with an apartment on the Rue de Rome as well as a summer cottage at 9 Boulevard Lannes.

In return, along with her charms, Laurent introduced Evans to a wide circle of artists and writers, who were her friends and sometimes her lovers. Because of her salon in the apartment he was bankrolling, Evans became a rather discriminating art collector, buying paintings by Manet and James McNeill Whistler, among others. He indulged himself in the occasional literary enterprise, writing an introduction to the English version of The Memoirs of Heinrich Heine. Mallarmé, in love with Laurent but willing to accommodate her wealthy American benefactor, was kind enough to call Evans’ piece a “subtle aesthetic piece of analysis.” He also accompanied Evans and Laurent on a 10-day trip to the spa at Royat, and included Evans on a list of close friends who were to receive a copy of his latest book.

For Manet, Laurent was a favorite model, a faithful friend and quite possibly a lover. He painted her as the chic personification of “Autumn” in 1881, though as his health declined, he turned increasingly to still-lifes with flowers, two of which would be bought by Evans. For many years after his death in 1883, Laurent would place the first lilacs of the season on his grave.

“Flowers in a Crystal Vase,” painted in 1882, is inscribed: “to my friend Dr. Evans, Manet,” though the relationship was probably based mostly on their mutual friends, especially Laurent. She was a kind soul and a stimulating conversationalist as well as a beauty, and she appears to have been about as faithful to Evans as he was to Mrs. Evans. One night he caught her sneaking off to meet Manet after she had pleaded a migraine, though it only took a few days of sulking and stroking for him to get over it.

“In her own inconstant way,” suggests Carson, “Méry Laurent was very much attached to the doctor.” Leaving Evans, Laurent herself once said, “would be a wicked thing to do. I content myself with deceiving him.”

Walter Cohen is sitting in his office in Center City Philadelphia, wearing one of those baby-blue smocks that dentists use to shield their shirts from spray and spittle. On a wall facing his desk hangs a framed copy of “Flowers in a Crystal Vase,” its colors slightly brighter than the original’s. Cohen, the chancellor emeritus of Medical College of Pennsylvania-Hahnemann University, still keeps up his periodontal practice, and is kind enough to squeeze in an interview about Evans between patients.

Back in the late 1940s, when he was a student at Penn’s dental school, the Evans Museum was open once a year, on Alumni Day. He still remembers visiting it as a junior and seeing “this beautiful writing table” that the czar of Russia had given to Evans, inlaid with photographs of Nicholas, Alexandra and their children. The whole museum, for that matter, was filled with the extravagant mementos of Evans’ life: paintings and jewelry and medals and tea services and snuffboxes—even Evans’ carriage.

But in the late 1950s, under the late Dean Lester W. Burket C’29, the school needed space for classrooms, and the museum was turned into the admissions emergency clinic. Its contents were cleared out. Some things went to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington; some were put in storage warehouses. Others ended up in dumpsters.

“When they cleared out the museum, things were thrown in the trash that people picked up,” says Cohen. “Faculty members told me that sketches, the death mask of Verdi, I think—things that were significant were just tossed out. That was traumatic. I’m glad I wasn’t part of that.”

But Cohen could not forget that table. When he became dean in 1972, he and a curator from the Philadelphia Museum of Art drove up to a warehouse in North Philadelphia, where the remains of the Evans collection were stored. They finally found the czar’s gift, which was badly warped.

Then, says Cohen: “I saw this lovely painting of a flower in a brioche, and it was signed ‘Manet.’ And I said, ‘Look at this!’”

The curator reminded him that some of the paintings in the Evans collection were not considered authentic, and Cohen acknowledged the possibility that the “Manet” was among them. But he liked it, so he took it back and hung it in his office, where it remained for several years, along with another “fake” Manet they had found, a lithograph titled “Polichinelle.”

The school, he decided, should take a detailed inventory of what remained of the Evans collection, with the idea of selling off its contents to form an endowment. (At that time, such decisions were in the hands of individual deans; now there is a centralized University policy for dealing with art.) They called in Christie’s, the auction house, whose consultants went through the collection.

“When they came to my office, they said, ‘What’s this?’” he recalls. “I said, ‘It’s signed “Manet,” but I’ve been told it’s a fake.’” Christie’s agreed, and valued it at $400.

In 1979, Dr. Paul Todd Makler M’43 GM’53, now curator of the University’s art collection, became a special assistant to President Martin Meyerson Hon’70 and recommended that an inventory of Penn’s entire art collection be taken. One of his first stops was the dental school, where he saw the painting of the brioche hanging behind a secretary’s desk. “I didn’t think it should sit there,” he says, “so I took it off the wall and brought it back on the trolley car to my home and said to my wife, ‘Look! We have a Manet!’ And then we started to look into the matter.”

Makler took it first to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, whose curator of French Impressionism did not think it authentic. Makler, unconvinced, then called an old friend: Anne Coffin Hanson, professor of art history at Yale University and author of Manet and the Modern Tradition. The painting “looked good” to her, recalls Makler, whereupon she went back and read the 1897 notaire’s list of Evans’ possessions when he died, and discovered that the dentist had indeed owned a number of paintings by Manet. One was an oil of a brioche, which Manet had mentioned in his expense book (“Evans, 1880, brioche … 500 [francs]”). Another was the lithograph of Polichinelle, “with the autograph signature of the artist.” Another was a “marine view.” Then there was one of flowers in a crystal vase—which, after another search of that North Philadelphia warehouse, was found, unframed, in a box of miscellaneous items. It was inscribed, “a mon ami le Dr Evans, Manet.” Hanson would later write up the story in an article for Art in America titled “A Tale of Two Manets.”

By then, a sympathetic judge had agreed to let the school “de-accession” its collection, and in 1983 the “Still Life with Brioche” and “Flowers in a Crystal Vase” were auctioned off for $2.1 million. “Brioche” now hangs in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh; “Flowers” is at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The “Polichinelle” lithograph went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

But the third oil painting by Manet, the “marine view” (“Beach, Low Tide”) that had hung in Evans’ operating office in Paris, was unaccounted for—until Cohen mentioned it to one of his dental patients: the late Violette DeMazia, curator of the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pa. She knew exactly where it was: in the Rockefeller collection in New York. The lawyer who settled Evans’ estate, she said, took it in lieu of a fee.

When Charles C. Harrison C1862, provost of the University, sailed to France in June 1897, he intended to talk to Evans about a possible legacy. That impending visit, notes Milton Asbell in his history of the dental school, was a “stimulus” to Evans, who reacted by “setting down in black and white very definite plans concerning the distribution of his wealth.”

But Harrison and Evans never got to have that talk. Agnes Evans died shortly before Harrison arrived, whereupon he learned that Evans had just sailed for America, intending to bury her in Woodlands Cemetery in West Philadelphia. Harrison promptly headed back to the United States, but he missed him on this side of the Atlantic, too. (According to Carson, Evans did have a “congenial meeting” with Harrison’s predecessor, Dr. William Pepper C1862 M1864, since Evans was then trying to convince French universities to recognize American college degrees.) And in November—almost exactly half a century after arriving in France—Evans died suddenly of angina pectoris at Bella Rosa.

He was buried in the mausoleum he had built for his family in Woodlands Cemetery, which is marked by a 150-foot, Washington Monument-like monolith that cost upwards of $100,000 in 1897 dollars. It still casts the longest shadow in the neighborhood.

Tom and Agnes Evans had no children. The closest he came to a dental heir was a former playmate of Lou-Lou’s at the Tuileries named Arthur C. Hugenschmidt D1885—who, at Evans’ urging, attended Penn’s new School of Dentistry, then gradually took over Evans’ practice, which he carried on, with considerable flair, for half a century. Evans had less luck with his nephew John Henry Evans, whom he had brought from Philadelphia to work as an apprentice in his office. The younger Evans so infuriated his Uncle Tom with his pretensions to nobility (and for swiping some of his patients and using the famous name Evans on a line of dental products) that the elder Evans tried—unsuccessfully—to have him deported. He also pointedly cut him out of his will, “for reasons as well known to the said John Henry Evans as to me.”

Many thought that Evans would leave his fortune—some $5 million in 1897 dollars—to the city of Paris, or for a museum there that would display his art collection and royal gifts. But when the will was opened, it provided for a museum and a dental school—”not inferior to any already established”—on his family’s property at 40th and Spruce streets in Philadelphia.

Evans’ relatives—16 of them, led by the said John Henry Evans—tried to overturn the will, on the grounds that he had left the money to the Thomas W. Evans Museum and Dental Institute, which did not actually exist at the time of his death. Years of legal wrangling followed. So did millions of dollars—not to mention a Manet—in lawyers’ fees. By the time the dust settled, the Philadelphia-based Thomas W. Evans Museum and Dental Institute Society was left with about $1.75 million—a goodly sum in those days, but not enough to build andstaff the kind of facility Evans had envisioned. The University had a keen interest in the outcome, but since it could not afford to look too interested, Harrison advised Dr. Edward C. Kirk, dean of the dental school, to “leave it severely alone.”

Finally, in 1912, a compromise was announced: the new institution would be called the “Thomas W. Evans Museum and Dental Institute School of Dentistry University of Pennsylvania,” and its board would be made up of trustees of both organizations. In May, 1913, the cornerstone for the handsome collegiate Gothic building was laid, amid much hoopla and praise for Evans. Among the well-wishers was the former Empress Eugénie, then 87 years old, who sent a letter congratulating Kirk on the “realization of the generous idea” of her late friend and protector.

“I am reminded of his sincerity,” she wrote, “the proof of which he gave me in the darkest hours of my life.”

Evans’ life inspired several books, many magazine and newspaper articles, and a number of doctoral theses, including Anthony Branch’s unpublished “Dr. Thomas W. Evans: American Dentist in Paris 1847-1897,” a copy of which is in the dental school’s library. But his story is one for the movies, really, and when Walter Cohen was dean of the dental school, he went so far as to pitch the film rights to “Masterpiece Theatre” and a few Hollywood producers. There was some interest, he recalls, but there was also one small catch.

The character of Evans, he was told, could not be a dentist.