A symposium remembers one of Philadelphia’s—and Penn’s—most important architects.

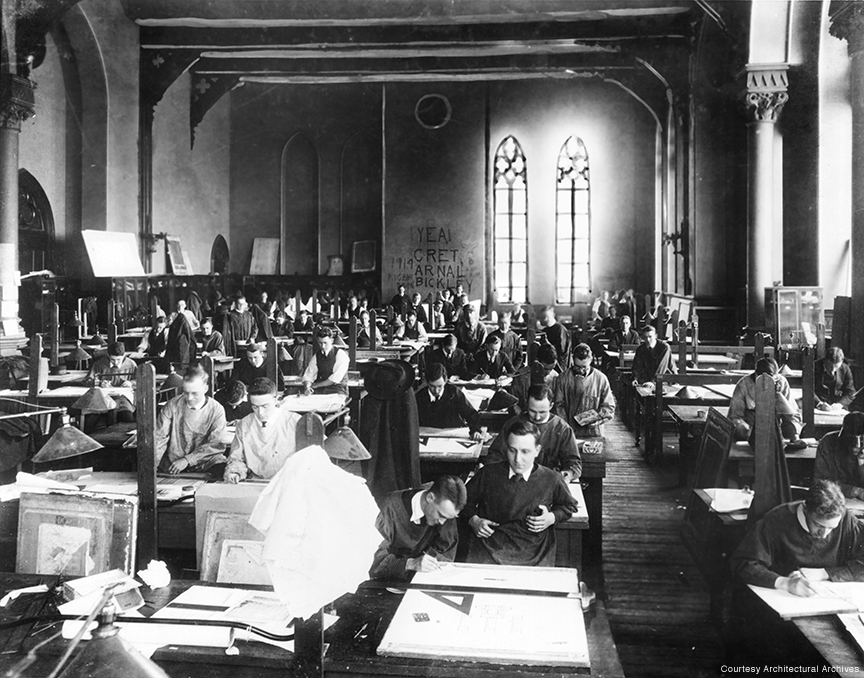

On a screen in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a vintage black-and-white photo of a packed Penn classroom appeared, labeled Architecture Studio. It depicted students under the tutelage of Paul Philippe Cret (pronounced Cray)bent industriously over their desks, while a scrawled message on the back wall proclaimed: “¡Yea! Cret.”

David Brownlee, the Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor of 19th Century European Art, paused for a moment as his audience burst into appreciative laughter. The graffiti, he said, provided an exclamation mark to the popularity of the French-born architect, whose students once voted him the most popular professor in the entire University. (Which does not mean that he was a pushover: one former student caricatured him as a “hovering t-square-wielding angel who admonished students, ‘You do not know what you are doing!’”)

Brownlee shared these anecdotes during a day-long symposium in May titled “Paul Cret and Modern Classicism.” Presented by the Athenaeum of Philadelphia and the PMA, the day of Cret offered a thorough and varied look at the architect who had such a profound impact on Philadelphia in the early decades of the 20th century. To coincide with the centennial of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Brownlee’s 1989 book Building the City Beautiful has been reissued, and the Athenaeum offered an exhibition titled: Professor Cret’s Parkway: One Architect’s Legacy on Philadelphia’s Grandest Thoroughfare. Cret, who designed the early plans of the Parkway as well as the Rodin Museum (1929) and the 2601 Parkway apartment building (1939), was also responsible for such Philly icons as Rittenhouse Square (1913), the original Barnes Foundation (1925) in nearby Merion, and the Benjamin Franklin Bridge (1927).

Born in Lyon, France, in 1876, Cret studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. That training prepared him to draw upon the neoclassical elements—arched windows, pilastered facades, bas relief panels—that would become the design tropes of the bank buildings, libraries, and museums of the late 19th century. But, argued Brownlee, once Cret arrived in the States—wooed by Penn, where he joined the faculty in 1903 and stayed until 1937—he advocated for a new form of classicism that later evinced some alignment with (if not total endorsement of) the radical attitudes espoused by Swiss modernist Le Corbusier. For Cret, architecture “was a matter of solving problems, not of imitating styles,” Brownlee elaborated. “Its beauty came from proportion, not from ornament.”

In 1907, notes Brownlee in his book, the Fairmount Park Art Association brought in Cret to tackle the problematic Parkway, then a proposed link between the city and Fairmount Park that had been stuck in the planning stages for decades, plagued by redesigns and setbacks. Although his scheme was approved in 1911, it too languished, when Cret left to fight for his homeland in World War I. The Association finally turned the project over to landscape architect Jacques Greber, who restored the early diagonal axis and widened it, laying out the Parkway as it is today.

Cret nevertheless managed to exert considerable influence on the Parkway, Brownlee told his audience, both by designing the Rodin Museum and by serving on a city-appointed art jury that weighed in on the design of public buildings. Even two buildings that gained approval while he was overseas—the Free Library and its companion Family Court, designed by Julian Abele Ar1902 (chief architect for the offices of Horace Trumbauer)— “did not escape without at least a symbolic critique,” observed Brownlee. “Cret chastised his fellow jurists [and wrote that] ‘it will be a matter of regret to some that such an important project built by the city will not deserve more than the doubtful praise of being a copy of a good example.’”

In discussing Cret’s work on the Rodin Museum, Brownlee pointed out that although his client, theater magnate Jules Mastbaum, instructed him to consider Versailles’ Petit Trianon while designing, Cret “diluted and simplified the classical details until they seem more like abstract geometry than historical citations.” In discussing another art-filled millionaire manse, the Merion-based Barnes Foundation (a new version of which would end up on the Parkway nearly a century later), Brownlee also saw modernity in its lack of corridors and its straight routes. The Barnes was a place that looked to the “strong and progressive” ornamentation of the Arts and Crafts movement, he added. It was also a space where “visitors were given no respite from looking.”

For Cret, modernism was a way of life, not just a style, Brownlee concluded. “His modern architecture was as varied and as complex as the modern world.”

Following Brownlee, French-born Marc Vincent Gr’94, a former professor of art history at Baldwin Wallace University, noted that Cret’s early Parisian mentors, Julien Guadet and Jean-Louis Pascal, had emphasized process, clarity, moderation, and avoiding an overly strict adherence to theory. Suggesting that Cret had taken those lessons to heart, Vincent summed up the architect’s approach as falling “between column and I-beam”—in other words, between classicism and modernism.

The most intriguing title of the day, Nioc! Nioc-Nioc!, went to Penn’s Alisa Chiles, a PhD candidate in art history. Cret had scrawled the French phrase (roughly translated as quack, quack-quack) on a photo of himself in uniform at the Battle of the Somme, an ironic comment on the patient trudge of his ever-marching troops. Besides such humorous touches, she said, his letters home also revealed the grave dangers he faced: Cret survived at least three gas attacks and narrowly missed being killed by German shells on at least two occasions. At one point, reports reached Penn that he had actually been killed in battle, causing great distress both on campus and throughout the city, she noted. Fortunately, those reports were wrong, though he did suffer permanent hearing loss.

After the War, Cret received the Croix de Guerre and designed several French battlefield memorials for Americans who had died fighting there. (By then he had designed a memorial at Valley Forge in 1914 and would go on to design another at Gettysburg in 1938.) After facing brutal, life-threatening hardships, Chiles summed up, Cret (who became a United States citizen in 1927) “translated his passion for Franco-American alliances into a new classical language of architecture that transcended national borders.”

Over the years, Cret and his architecture courses steadily gained in reputation at Penn, sending forth a steady stream of future architects whose work was regularly recognized by national organizations. But his real legacy was his own work in his adopted city.

“Cret is by any measure one of the major architects of the 20th century,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Paul Goldberger in his keynote address. “The modern classicism of Philadelphia, and particularly of Cret, possesses a grace and subtlety … Monumentality, well-executed, is a gift which reminds us that Philadelphia is a city that believes in the public realm.”

—JoAnn Greco