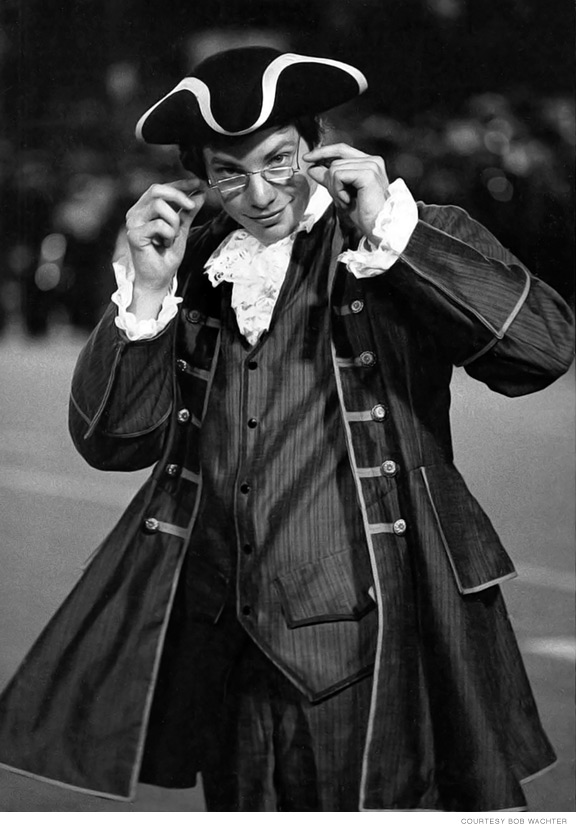

This influential San Francisco physician—and former Quaker mascot!—distills pandemic information for the masses.

As Robert “Bob” Wachter C’79 M’83 called his son on the morning of January 6, the calculated, rational part of his brain faced a conflict.

As a doctor, Wachter knew that statistically his 28-year-old son’s COVID-like symptoms were probably nothing to be concerned about. His son was triple vaccinated, “generally healthy but overweight,” and careful about limiting contacts despite a public-facing customer service job. He tested negative the day before despite worsening symptoms. At the height of the Omicron variant wave, if he’d come down with a case as so many millions had, it was probably no reason to panic.

But as a father, Wachter grew increasingly worried when his son didn’t pick up the first time he called. Or when he again got no answer an hour later. Almost by reflex, worst-case scenarios flashed through his mind.

“He’s a young guy whose main risk factor is his weight and he’s had three shots—he’s not going to die,” Wachter says. “He’s probably going to have a fairly mild case. But the morning after, when I called him at 9 and he didn’t answer the phone and I called him at 10 and he didn’t answer, it dawned on me that maybe he’s in his apartment and he’s dead.

“That was a completely irrational, non-doctor, non-scientist way of processing the information, but perfectly human as a father. And I think everyone has gone through versions of that.”

As he has so often over the last two years, Wachter expressed those emotions on Twitter (@Bob_Wachter), where he’s grown his following to more than 250,000 as one of the most trusted and cited sources of public health and policy information surrounding the pandemic.

It’s the latest turn for Wachter, who serves as chair of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and has consistently been ranked as one of the most influential physician-executives in the US by Modern Healthcare magazine. His online blend of reliability and relatability that made the 25-tweet thread about his son go viral has brought comfort and clarity to thousands trying to make sense of the pandemic. (His son ended up being fine, and “with three shots plus a breakthrough—about as immune as you can be,” Wachter tweeted when his son’s rapid test finally turned negative 10 days after the first positive.)

Wachter was hardly an obscure figure before COVID-19. He’s written six books and hundreds of articles—“a generalist in every sense of the word” whose interests run the gamut. “I’m what happens when a political science major becomes an academic physician,” says Wachter, whose books The Digital Doctor (2015) and Internal Bleeding (2004) were excerpted for essays in the Gazette [“Expert Opinion,” May|Jun 2015 and May|Jun 2004].

Wachter describes his career as “a series of pivots,” beginning with the Long Island native visiting San Francisco on a whim thanks to an old Eastern Airlines promotion that offered a flight anywhere in the country for the same fixed price. He never left, building his career out west as an academic physician interested more in broad thinking about delivering care than any particular specialty.

In 1996 Wachter authored a landmark paper on patient care in hospitals—the paper went from a staff newsletter at UCSF to a much larger audience at the New England Journal of Medicine—which led to hospitals nationwide hiring “hospitalists,” a term he coined. Essentially, Wachter identified the need for hospitals to invest in in-house physicians devoted specifically to inpatient treatment, instead of a patient’s general practitioner visiting when they could, to improve patient outcomes and lower costs.

More than two decades later, when COVID-19 began to bring normal life to a halt, it quickly became clear that a generalist like him could be valuable. Beyond infectious disease studies, the global crisis entailed many different disciplines—epidemiology, aerosol science, supply chain management, economics. Wachter saw a need for a “synthesizer,” someone comfortable in digital spaces who could identify trustworthy information and distill it into language the public could grasp.

“I was scared, and being useful felt good,” Wachter says. “I saw the entire world, my immediate world and then the world writ large, was trying to figure out what is this thing and how scary is this thing and is it the end of the world? I found it a useful and somewhat comforting thing to do.”

Wachter’s role as a chair of medicine has always involved identifying experts in their individual realms and making their knowledge transferrable. Being a go-to source for media organizations is an extension of that. Twitter, meanwhile, provided a global reach, and his interactions with people on the platform have generally been positive. A typical Wachter thread includes charts and images to aid understanding, and he enjoys the “forced discipline of brevity” required with 280 characters.

He’s also been unafraid to take controversial positions. He described a “moral obligation” to highlight government policies that data suggested would cause avoidable deaths. While he knows politics and healthcare can never be separated, his position offers more leeway than most to speak his mind. “For me to say I can’t touch that because it’s politics just felt really wrong and inauthentic,” Wachter says.

He comes back to that word often: authentic. Wachter felt it when he served as the Quaker mascot at Penn during the 1978–79 men’s basketball Final Four campaign. During games, Wachter played a character, the most uninhibited version of himself, to try to get the crowd going. After the game, he’d mingle with alumni in cocktail receptions, requiring a much more sober—“in both meanings of the word”—temperament. His ability to meld those disparate perspectives continues to serve him now, albeit with far greater stakes.

“I think that’s been a little bit of a theme for my career and a little bit of a theme of my persona during COVID—a willingness to be more out there, more personal, more authentic, more vulnerable, and at times, I hope, funnier than I think the usual physician and scientist,” Wachter says. “And there’s also an ability and willingness to be sober and factual and evidence-based and reassuring and useful, as a doctor and a scientist should be.”

—Matthew De George