A fall conference and ongoing exhibit highlight the work of Penn-trained architects in China.

By Ted Mann

As one of the dominant architects of the early 20th century, Paul Philippe Cret designed some of Philadelphia’s most enduring landmarks: the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, Rittenhouse Square, and the Rodin Museum, to name just a few. Cret was a star graduate of France’s École des Beaux-Arts, and, when he arrived at Penn in 1903, he quickly established the School of Architecture as one of the strongholds of the Beaux-Arts method. Before long, Cret was drawing students from all over the world—particularly China.

Today, many of Cret’s bold creations still stand—from the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, a Parisian axis into the Quaker city’s grid, to the University’s 1940 chemistry building, an early stab at modernism—but his legacy in America has been somewhat eclipsed by his students, most notably Louis I. Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71. In China, however, Cret’s influence has proven to be remarkably enduring. His foreign students from the 1920s became prolific builders, revolutionary city planners, and, most important, educators that established China’s first architecture schools and curriculum, based in large part on the Beaux-Arts method.

After being overlooked during China’s long architectural dark ages—the concrete-ridden period under Mao—these Penn alumni have finally begun to receive attention. This past fall the School of Design and the Department of Architecture hosted an international conference, “The Beaux-Arts, Paul Philippe Cret and Twentieth Century Architecture in China,” to celebrate these Chinese architects and their contributions. According to Nancy Steinhardt, Professor of East Asian Art and one of the conference’s organizers, “It was something that people have wanted to happen for decades.”

The conference, held October 3-5, drew 400 people, according to Steinhardt. Some were descendants of the 1920s alumni; others were working Chinese architects and scholars. After the first day’s talks, guests crowded into the Architectural Archives for the christening of “The Beaux Arts at Penn,” a new exhibit featuring drawings, watercolors, and blueprints created by Cret and his students that runs through May.

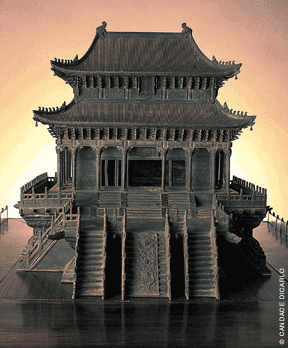

Standing proudly at the entrance of the exhibit is a restored bronze miniature of a hall from the Imperial Palace in Peking. A small plaque on the base explains that it was presented to the University by Robert Fan Ar’21 and the Chinese student alumni association from the 1920s on the occasion of Penn’s bicentennial in 1940. The model was long thought to have been lost, until University Archives collection manager Bill Whitaker GAr’88 and conference co-organizer Tony Atkin GAr’74 unearthed it from deep in the archives under Franklin Field, where it had collected soot for decades.

For Atkin, an adjunct professor of architecture and partner in Atkin Olshin Lawson-Bell Architects, what was intriguing about the 1940 gift wasn’t the design of the building or its historical details, but rather the close-knit, influential group that gave it. “The sense of esprit de corps that developed among these Chinese students during their years at Penn carried over into their architectural practices and teaching careers,” says Atkin.

In all, 25 students came to study with Cret during the 1920s, mostly through the aid of Boxer Indemnity Scholarships. In China, these alumni continued to meet and collaborate for decades, many teaming up to launch the country’s first architecture programs.

The most famous of the group was Liang Sicheng GAr’27, who founded an architecture school at Tsinghua University. Arguably the most prestigious program in China, Tsinghua follows much of the Cret-influenced curriculum that Liang imported. Modern-day students still must take watercolor and drawing courses, a requirement of the Beaux-Arts method. Currently, Atkin is running a joint-studio program with Tsinghua, where Penn grad students collaborate on urban redevelopment projects in Beijing. Christopher Ford C’95 GAr’04 worked on a project to develop the Temple of Agriculture, a complex of ramshackle garages and sheds, into urban housing designed so as to preserve the site’s architectural history. While many of the new skyscrapers in Shanghai and Beijing pay little attention to China’s past—“They’re like something from The Jetsons,” says Ford—there is finally a movement to preserve the country’s ancient, historic buildings. The preservationist cause, it turns out, also has direct ties to Liang Sicheng.

Liang spent much of his life compiling a history of ancient architecture in China. He traveled the country with his wife, Lin Huiyin FA’27 (a classmate at Penn, never recognized by the male-only School of Architecture), surveying and documenting every variety of traditional Chinese forms—from pagodas and temples to garden “moongates” and window latticework.

Tragically, Liang never lived to see the impact of his magnum opus, A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture. Published posthumously in 1984, it quickly became a seminal text. “People still read it as their first textbook on Chinese architectural history—for better or for worse,” said Nancy Steinhardt. “He’s almost like a cult figure.” Incredibly, there’s even a Hong Kong soap opera based on the life of Liang and Lin.

Another maverick of Chinese architecture was Yang Tingbao Ar’24. Like his classmate, Louis Kahn, Tingbao was one of Cret’s star pupils, though he remained a closer adherent of the Beaux-Arts style. At the Nanjing School, in southern China, he emphasized many of Cret’s tenets, such as designing a building around the “programs” it houses, not the exterior façade. Axial planning, space perception, and a close collaboration between architects and builders were all part of his teaching method. And like Cret, Tingbao didn’t just espouse architectural theory—he turned it into bricks and mortar. Shenyang Railroad Station (1927), Tsinghua University Main Library (1930), and Nanjing Central University Library (1933) are just a few of his more programmatic, Beaux-Arts influenced creations.

Among those in attendance at the October conference were Tingbao’s son and granddaughter, both of whom are keeping up the Penn architecture legacy. Tingbao’s son, Shixuan Yang GAr’88, is an architectural historian who has taught at Tsinghua and currently works with I.M. Pei in New York. Tingbao’s granddaughter, Benyu Yang GAr’04, is a graduate student in the architecture program.

Although Benyu knew of her grandfather’s work, the influence of Penn’s other Chinese alumni was a revelation. “I was shocked how wide the impact was,” she said. Benyu studied architecture in Beijing, but not all of the Beaux-Arts teaching methods sat well with her. She singles out the two-year drawing requirement as a sore point. “Why spend so much time rendering by hand. That’s what computers are for!”

In her Penn classes, she says, “The teaching method is very different.” The emphasis on research, study-abroad, and apprenticing with international architects has completely changed her preconceived notions of architecture. Benyu will graduate this May, 85 years after the first Chinese architecture student, Chu Pin. She ultimately hopes to return to China to partake in the Olympics-fueled building boom that’s swept the country. But, unlike her grandfather, don’t expect Benyu’s buildings to be prototypical Beaux-Arts. “It’s time for a change,” she says.

Ted Mann C’00 has written for the Gazette on a scientific study of the Atkins diet, the extinction of giant mammals, and young Penn alumni comedians.