As a young federal civil rights prosecutor, Jared Fishman C’99 investigated the police killing of a Black New Orleans resident in the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Now, after writing a book on what he calls “one of the most egregious cases of police misconduct in recent American history,” he’s tackling criminal justice reform on a broader scale.

By Dave Zeitlin | Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

Book Excerpt | Us and Them

Think about the most heinous police killings in recent American history. What comes to mind?

Undoubtedly George Floyd pinned to the pavement, an officer’s knee on his neck. Maybe Philando Castile in his car, Breonna Taylor in her apartment, or Tamir Rice at a park. Eric Garner pleading “I can’t breathe” while locked in a chokehold on a New York City sidewalk has left an enduring mark, his final words becoming a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.

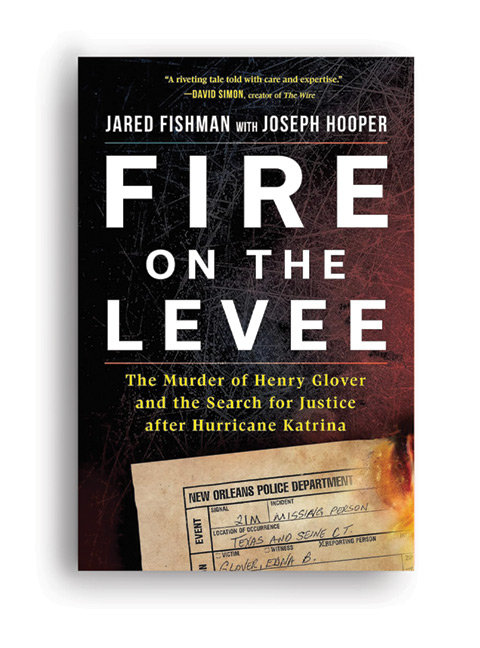

It’s less likely you thought—or even knew—about the killing of Henry Glover, a 31-year-old Black resident of New Orleans who was shot by a police officer in the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005—and whose body was subsequently burned by another officer. That’s why Jared Fishman C’99, a former prosecutor for the US Department of Justice who investigated and tried the case, sought to bring it to light by coauthoring, with magazine writer Joseph Hooper, the book Fire on the Levee: The Murder of Henry Glover and the Search for Justice after Hurricane Katrina (Hanover Square Press, 2023).

“What surprised me at the time—to this day—is that one of the most egregious cases of police misconduct in recent American history is not on anyone’s radar,” says Fishman. While the story did generate local coverage in New Orleans and national attention during the trial, “it did not spur the kind of outrage that we have seen after Michael Brown was killed, or Freddie Gray, or Walter Scott, or obviously George Floyd,” he continues. “It didn’t make sense to me. I knew this was an important story, I knew this was a gripping story. To me, it speaks a lot about humanity, our society, its ability to police itself, and what happens in the event of a societal breakdown.” On top of all that, Fishman adds, “it really helps explain just how broken the American criminal legal system is as a whole.”

Fishman was a junior attorney in the criminal section of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice in January 2009 when, more than three years after Katrina, a thin brown folder appeared on his desk in Washington, DC. “The folder contained only two items,” he wrote in Fire on the Levee. “One was an autopsy report that briefly detailed what was left of the incinerated remains of a man named Henry Glover. The other was a recently published article from The Nation, which raised questions about Glover’s death.” Stuck to the front of the folder was a handwritten yellow Post-it note from one of the deputy chiefs in his department: “I don’t know if there is anything to this, but at least this should be interesting.”

Nowadays, since “cases are almost all generated by videos” (typically horrifying cell phone footage that goes viral), Fishman doesn’t think a file like that would land on anyone’s desk. Even with video evidence, it’s proven exceedingly difficult to charge and convict police officers, for reasons ranging from the legal doctrine of qualified immunity to a “blue wall of silence” among departments and police unions that protect their own. But for the next 19 months, Fishman teamed up with a rookie FBI agent named Ashley Johnson to try to find cracks in the protective and notoriously corrupt New Orleans Police Department (NOPD). “It was definitely intimidating,” Fishman says. As he and Johnson set up interviews with the officers they believed to be involved in the killing and ensuing coverup [see excerpt], he heard that police had tagged the pair with a nickname “the Black girl and the Jew.” It put Fishman on notice: “We were going up against very angry cops.”

The investigation was arduous, slow, and draining. Given that the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office had not even ruled Glover’s death a homicide—and for years no one had investigated the mysterious circumstances surrounding it—Fishman and Johnson started with little to work with, apart from The Nation article written by investigative journalist A.C. Thompson. In that piece, Thompson drew from eyewitness accounts to paint a picture of Glover’s final hours: On September 2, 2005—about a week after Katrina pummeled the region, leaving some stranded survivors to scavenge for food, water, and shelter—Glover was walking with his friend Bernard Calloway near a deserted strip mall in the New Orleans neighborhood of Algiers when a single shot rang out from a second-floor breezeway. Glover crumpled to the street, bleeding. Calloway sought the help of Glover’s brother, Edward King, who lived nearby. Both Calloway and Glover then flagged down a Good Samaritan named William Tanner, who loaded the three men into his Chevrolet Malibu and drove off in search of help. Believing that the nearest hospital was too far away, Tanner decided to drive to Paul B. Habans Elementary School, which had been commandeered by members of the NOPD’s Special Operations Division in the wake of Katrina. But instead of receiving help at the makeshift police base, the men were allegedly beaten and handcuffed by the officers, who took them for looters, while Glover remained in the car, where he was given no medical aid. “They ain’t much touched him,” Tanner later told Fishman. “That was the cruelest thing a person can do to a man, let him bleed to death in a car like that.” Calloway, King, and Tanner were eventually released, though the Chevy remained in police custody. Glover’s charred body was later found inside the burned shell of the car next to a Mississippi River levee.

As Fishman got to know Tanner and members of Glover’s family, his resolve stiffened. Glover hadn’t been the only civilian shot by police in that time period; reports later surfaced that cops had been authorized to shoot looters. His hunt for justice was intensified by several desires: to help the Glover family find some semblance of peace in the wake of so much trauma; to destroy the NOPD’s blanket attempt to justify post-Katrina misconduct by characterizing the period as “not normal times”; and to hold officers accountable and bring about lasting change at the departmental level.

Not least of all, Fishman’s quest to find justice for Henry Glover was fueled by another unjust and tragic killing, a decade earlier and 7,000 miles away.

Between his junior and senior years at Penn, Fishman looked ahead to summer internships, blasting out his resume “to investment banking firms and consulting firms and tech firms because that’s what everyone else did.” But when his friend and classmate Leslie Adelson Lewin C’99 suggested he join her as a counselor at Seeds of Peace Camp in Maine (which brings together young people from conflict zones across the Middle East), he quickly switched gears. “I was like, ‘Yeah, I’d much rather be doing that.’”

Growing up in a middle-class Jewish community in Atlanta, Fishman had been interested in war and conflict from an early age. His grandparents escaped Austria in the late 1930s before the Nazis exterminated much of their community, fleeing to the US where their son, Fishman’s father, managed to build a successful accounting practice. Learning about the Holocaust shaped Fishman’s worldview, and he strove to honor the Jewish concept of Tikkun olam, which refers to repairing the world.

Yet in reality, he wrote, “my world was very small, the homogenous bubble of prosperous suburban Jews I spent my days with, from school to after-school sports to summer camp.” It wasn’t until arriving at Penn that he tried to see things beyond his Jewish lens, majoring in Middle Eastern Studies and taking courses on Islam and politics in the Middle East. “I didn’t know any Arabs before I went to Penn, and I certainly wasn’t well versed in the perspective of Palestinians and how they thought about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict,” he says. With the prompting of his college advisor Roger Allen, Emeritus Professor of Arabic Languages and Literatures, Fishman went to Morocco the summer after his sophomore year to study at the Arabic Language Institute in Fez. Traveling independently and depending on the kindness of others, he had “probably the most profound, life-changing experience at that stage of my life,” he says.

At least until the following summer. At Seeds of Peace Camp, “that was the first time I lived with Palestinians,” Fishman says. “That was the first time I lived with Jordanians. I lived with Israelis. I lived with kids from Qatar, Tunisia, and Cyprus.” His role as a counselor, in many ways, was just like it would be at any summer camp. “What do you do when there’s this conflict between teenagers being teenagers, totally independent of the politics of the region?” he says. So in addition to fostering challenging conversations on peacebuilding between Jews and Arabs, Fishman often found himself navigating situations like “Who gets to shower next?” and “What are you going to do if a kid’s shoes are really stinky?”

Lewin, who’s remained close with Fishman since their time together at Penn and Seeds of Peace, recalls her friend “helping to bridge the balance” between complicated talks and moments of levity. And she still has a vivid memory of Fishman playing his guitar in front of the camp assembly. “I feel like Jared screams camp counselor,” she says. “He brings a sense of joy and passion and humor, but underneath it there’s also a real sense of purpose and a real commitment to wanting to do good work.”

For Fishman, it was a hopeful time and “so moving to be able to see these kids who are coming from war zones, who had very real traumas in their own experiences, being able to work together to come up with solutions to the problems that were facing their communities.” But the hope didn’t last long. After graduating from Penn, Fishman moved to Jerusalem to help launch the Seeds of Peace Center for Coexistence, where he designed year-round conflict resolution programming for youth leaders. On the one-year anniversary of his arrival in the region, the Second Intifada broke out as peace talks between Palestinian and Israeli leaders broke down. Whereas Fishman had once taken Israeli kids into Palestinian refugee camps and Palestinian kids into Israeli schools—“The power of humanity at its best,” he recalls wistfully—“violence quickly took over life and we could no longer transport people across borders,” he says. “It transformed society overnight, in ways that have only gotten worse.” (Fishman’s words seem even more prescient in light of Hamas’s October 7 assault on Israel and the ensuing war in Gaza. When contacted in the immediate aftermath of the attack, Fishman wrote: “It is hard to remember that there was once a time when peace was a real possibility—I remember that time—but it was so easily destroyed. It continues to be devastating how civilians continue to experience the trauma of war.”)

On October 2, 2000, a few days after the start of the Palestinian uprising, Fishman was working in Jerusalem when a gut-churning phone call came in. A gregarious and beloved Seeds of Peace camper named Asel Asleh had been shot. Fishman couldn’t believe it. Asel, an Arab citizen of Israel, “was the kid who could move others along,” Fishman remembers. “He was such a leader. His presence was overwhelming. And he stood for all of the things we cared about.” Asel had been wearing a Seeds of Peace T-shirt while at a protest near his village of Arraba—seemingly off to the side and out of harm’s way, according to Fishman, who provided this account in his book: “Suddenly, two groups of officers charged towards the crowd, which dispersed in panic. Multiple officers chased Asel into an olive grove. Several times, he slipped and fell while being chased by the police. One officer caught up to Asel, hit him in the back of the head with the butt of a gun, and then shot him in the back of the neck at close range. A police checkpoint prevented his ambulance from reaching the hospital in time. He died en route.”

Asel was one of 13 Arab citizens of Israel killed during protests in Arab villages that month, and a commission was later established by the Israeli government to investigate the police response to the rioting. Although the commission concluded that excessive force was used, no officers were ever prosecuted. “I think about what Asel’s family never got,” says Fishman, who called the killing “the death of hope.”

Seven months into the fighting, Fishman returned to the US to enter law school at George Washington University. During law school, he spent two summers in Bosnia running a reconciliation program following the Bosnian War. After that he tried to help restore justice in postwar Kosovo and Rwanda while working for the US Department of State. He always kept the Asleh family in his mind, “any time I had to go interact with a family who lost their loved ones to police violence.” That would come to include Henry Glover’s family.

“Asel’s and Henry’s deaths felt similar,” Fishman wrote. “Coincidentally, Asel had been killed on Henry’s birthday. When I got back from one of my first trips to New Orleans, I framed an old picture of Asel and hung it in my office at the Justice Department as a reminder. No one had ever been held accountable for Asel’s death. I hoped to do better for Henry’s family.”

Walking down the center aisle of a large cherrywood New Orleans courtroom in 2010, Fishman felt a rush of emotions.

After a 19-month investigation into Henry Glover’s killing, a grand jury had returned an indictment that brought 11 charges against five officers. The charges could be divided into three different sections, as Fishman wrote: “the shooting at the mall; the beating at Habans and the burning at the levee; and the false reporting that followed.” A rookie officer named David Warren, who admitted to firing a shot at Glover, faced the most serious charges, thanks in part to a damning firsthand account provided by his partner Linda Howard, who attested that Glover was unarmed and running away when Warren fired his personal assault rifle at him, from an elevated position and without any justifiable reason to feel threatened. “During the twelve subsequent years that I investigated police misconduct, I never met another police officer who was so forthcoming with incriminating evidence against a fellow police officer,” Fishman wrote.

But Fishman still knew how challenging it would be to land a conviction since police shootings of civilians remain notoriously difficult to prosecute. And as much pressure as he felt during the investigation, it was even amplified during the arraignment and trial in a packed courtroom, with “a lot of people pulling for me and a lot of people rooting against me.” (By then, the FBI and DOJ had provided Fishman and Johnson with more resources and support from other attorneys, though Fishman was surprised, given his inexperience at the time, that he remained the lead prosecutor in what had become a high-profile case.)

“My first thought was that this was like attending a tense wedding where the bride’s and groom’s families hated each other,” he wrote. “The second, more disturbing feeling was that I was stepping back fifty or a hundred years into the Jim Crow South, strictly segregated by custom and law.” As it is in many police shootings, race had been a factor throughout the investigation and trial, since all the implicated officers were white and all the victims Black. Though there wasn’t sufficient evidence to charge Warren with a federal hate crime, Fishman wrote that he “was certain the perception of race influenced the speed with which Warren used deadly force.”

In the end, after an intense weeks-long trial that Fishman richly details in his book, the federal jury found Warren guilty of a civil rights violation, resulting in death, as well as use of a firearm during a crime of manslaughter. Greg McRae, a veteran NOPD officer who admitted to driving away with the car and burning it with Glover’s body inside, was convicted on two counts of civil rights violations and obstruction of justice. Travis McCabe was also found guilty of obstructing justice and perjury. The other two officers on trial, Dwayne Scheuermann and Robert Italiano, were acquitted for their alleged roles in the burning of the car and participating in the coverup, respectively.

Though he was reassured by the smiles he saw from Glover’s family after the verdicts were read, the jury’s decisions felt like an incomplete victory for Fishman. It would soon become even more frustrating. Warren, who had been sentenced to nearly 26 years in prison, was granted a new trial after appealing to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals (which “has historically gone out of its way to protect police officers,” Fishman wrote) that he suffered prejudice by being tried alongside the officers accused of burning Glover’s body in a separate incident. And in the December 2013 retrial, another jury found Warren not guilty following a long deliberation. Fishman recalls seeing half of the 12 jurors in tears when the verdict was read. Glover’s sister, Patrice, had to be carried out of the courtroom, shrieking in agony. “I just felt numb,” Fishman wrote.

Yet Fishman had always felt ambivalent about prison sentences, calling it “perverse that the prize for a hard-fought victory in court is another human winding up in a cage.” So he was pleasantly surprised that McRae, whose 17-year sentence was reduced by more than five years, agreed to speak with him not long after being released from jail. “I had never spoken to anyone I had sent to prison before,” says Fishman, who recounted their talks, held between May and November 2022, in his book’s epilogue.

McRae—whose main defense for incinerating Glover’s body rested on his claim to have been mentally unhinged by rescue operations during which he saw bodies floating in flood waters and dogs feeding on human remains—was emotional in those conversations. He insisted he had no idea Glover had been shot by another officer and he called Warren “a coward … [who] should never have been a police officer,” according to Fishman. He also referred to his departmental reputation for cleaning up messes and said a captain had told him to “get rid” of Glover’s body. Though McRae said none of his colleagues knew the specifics of his disposal plan beforehand, they did know the car was burned after the fact. “It has always been hard for me to look at McRae and not see a guy thrown under the bus by the entire police department,” Fishman wrote.

Those conversations solidified Fishman’s view that police misconduct almost always goes deeper than one “bad apple,” and that sending a few police officers to prison is akin to putting a little Band-Aid on a gaping wound. “Way too often when we talk about our criminal justice system, we tend to think of good guys and bad guys,” he says. “One of the things I really wanted to emphasize in the book is that it’s not just individual decisions; people are always operating within a context and within a system. And that system contributes in major ways to the outcomes that we get in our communities. And so often, after a lot of the police misconduct cases I would do over the course of my career, when we got a conviction, everyone washed their hands and said, ‘We got the bad apple. This is not who we are.’ But when you actually start to break down individual cases, it’s not just about bad apples—it’s about cultures of silence that enable bad conduct to stay; it’s about training; it’s about a denigration of the communities that we are supposed to be protecting.”

Not long ago, Fishman realized prosecuting bad cops wasn’t enough. He had a new project in mind.

Four years after a jury acquitted David Warren, Fishman led the DOJ team that prosecuted Michael Slager, a local police officer in North Charleston, South Carolina who gunned down Walter Scott in 2015. Scott, a 50-year-old Black man, had been pulled over because of a malfunctioning taillight. A passerby took video of an unarmed Scott running away from the traffic stop and being shot in the back by the white officer—“the clearest evidence I had ever seen of a bad shooting,” wrote Fishman. Slager pleaded guilty to a federal civil rights violation and was sentenced to 20 years in prison, which Fishman called “a result as good as any we could have hoped for.”

And yet, standing on the courtroom steps in 2017, “after winning what was arguably the biggest victory of my career,” Fishman felt empty inside. “I get that this is rare,” he remembers thinking. “But now what?” He was more interested in figuring out why Slager pulled over Scott in the first place and how his death—and the deaths of so many other Black people at the hands of police—could have been prevented. Winning cases, while important, wasn’t enough to spur real, lasting change.

Following the Scott verdict Fishman spoke regularly with Scarlett Wilson, the Charleston solicitor who prosecuted Slager for the state, about ways to make Charleston’s criminal justice system more equitable. She had been collecting data about who was being arrested, charged, and incarcerated to potentially identify racial disparities. Intrigued, Fishman pivoted in that direction. In 2020 he left the DOJ to launch the Justice Innovation Lab (JIL), a non-profit initiative that designs data-driven tools to create a fairer and more effective justice system. Per JIL’s mission statement, “our goal is to reduce harmful outcomes, including over-incarceration and unjust racial and economic disparities. Our team of data scientists, human-centered design experts, prosecutors, policymakers, and community advocates support local leaders in identifying unfair practices and developing effective alternative solutions.” (Fishman’s longtime friend Leslie Lewin is an operations advisor.)

JIL’s advisors are scattered around the country—“being an organization that was founded during the pandemic, we never had an office building,” Fishman says—and focus on helping specific local jurisdictions. “We often think about the American criminal justice system as if it were just a singular thing, but that’s the wrong way to think about it,” Fishman says. “In reality, we have about 2,300 justice systems in America, most of which function at the county and city level, almost all of which function virtually independently in terms of how they make decisions.” And most of them, Fishman posits, “want to do better and simply don’t have the tools or the necessary support to do it.”

So where does Justice Innovation Lab come in? Here’s one example: In Charleston, JIL helped the city determine that 25 percent of their cases were being dismissed for insufficient evidence—“a huge amount of wasted resources,” Fishman says—and that it was taking more than 200 days for that failed process to play out. During that extended period, a person who had been arrested might be incarcerated, lose a job, and pay some sort of bond, “usually on the backs of the poorest people in the community, all on a case that prosecutors don’t think should be there.” Fishman says JIL helped the city create a new screening process to determine a case’s merit on “the night of the arrest or as close to it as possible” through a data-driven pilot program managed by a part-time attorney. The city has since expanded the screening process and is “actually changing how they communicate this with the police,” adds Fishman, who notes that officers who make “bad arrests” are often young and inexperienced. “So now they get notified why the case is insufficient.” On a broader scale, Fishman hopes that will lead to positive feedback loops and fewer bottlenecks in the justice system, since bottlenecks “almost always result in injustice.”

Here’s another example: In Saint Paul, Minnesota, JIL did a project on pretextual traffic stops (in which officers pull someone over for a minor offense before searching for evidence of an unrelated crime). These stops have unfairly targeted minority motorists, critics claim, and lead to about 10 percent of police killings each year. “And the research showed there that you can stop doing this very ineffective and discriminatory practice without negatively impacting public safety,” Fishman says.

Meanwhile, the organization is working in Memphis, Tennessee, to help decisionmakers identify cases that can be safely removed from the criminal justice system and transferred to the public health system, which he believes would be better able to address underlying mental health problems.

In speaking with police officers, Fishman says many of them admit they’re ill-equipped to deal with America’s mental health crisis, or drug abuse, or poverty. “Most of them wake up every morning and their goal is to serve their communities,” he says. “They want to live in safe communities, and they want to live in fair communities. And yet they operate in a system that routinely leads to bad outcomes”—and one in which they’ve traditionally been judged by metrics such as how many arrests or traffic stops they make.

The murder of George Floyd, which occurred shortly after JIL’s founding, “infused a new energy and new funding opportunities” for the organization, Fishman says. But he’s seen a backslide since then. Police killings reached a record high in 2022. “There are definitely days where it feels overwhelming because I would like to fix the whole problem,” Fishman says. “But the exciting thing is that each county has the ability to innovate, and so we can transform our criminal justice system one county at a time.”

He can look to the city where it all began for him for some bit of solace. After the Katrina-era federal prosecutions, “New Orleans began remaking its police department in a way that no previous police scandals had ever managed to inspire and that, pre-Katrina, few people would have ever thought possible,” Fishman wrote. At least 25 officers were fired or resigned under investigation, and “for the past decade a team of federal court-appointed monitors have worked with the department to reassess every aspect of the job, from training and hiring protocols to ‘use of force’ procedures, evaluating the department’s progress along the way.” Far fewer civil rights cases are now being brought against the NOPD. And the city recently created an innovative peer intervention program called EPIC (Ethical Policing is Courageous) to help officers police each other and not look the other way when they see misconduct.

“We must chase justice,” Fishman wrote in his book’s final chapter. “It is an active pursuit. It can be slippery and hard to nail down. It can be exhausting. Chasing justice comes with the understanding that, far more often than we’d like, it will get away from us.

“Our current criminal legal system is the result of choices made by many individuals over a long period of time. Some of these structures and practices were deliberately built to oppress others; sometimes, the harms are merely unintended consequences. People created these problems; people can fix them.”

EXCERPT

Us and Them

When federal prosecutors and investigators take on corrupt local cops, one stakeout a time.

In late May, I found myself bleary-eyed in Ashley’s car, parked under old-growth oak trees. We sat outside of David Warren’s house in Algiers on a bucolic suburban street, a departure from the more neglected neighborhoods where Ashley and I spent much of our time. It was 6:00 a.m., and I was mindlessly sipping bad hotel coffee to stay focused. Neither one of us had gotten enough sleep. Ashley had been up since 4:00 a.m., executing a search warrant in another case. I couldn’t sleep in anticipation of my first opportunity to come face-to-face with the man who killed Henry Glover.

Our hope was that we would catch Warren leaving for work—he had recently left the New Orleans Police Department to work for an electrical utility company—or at least, we could catch him at home after the kids had left for school. We figured that approaching him alone, by surprise, might improve our chances that he would speak to us.

We hunkered down for a stakeout. I was excited, even though Ashley’s supervisor Kelly had warned me that stakeouts generally involve a lot of sitting around waiting for something interesting to happen that rarely does. This early in the morning, the only thing going on was the chirping of a mockingbird.

By this point in the investigation, Ashley and I had spent a lot of time in the car talking through the case. The thing we discussed most was the mystifying link between the shooting of Glover and the incineration of his body.

We had run into one roadblock after another trying to unravel the burning. Three months into the investigation, we didn’t know much more than what The Nation had reported in December 2008. Our one significant advance, thanks to the date stamp on the photos taken by the Customs and Border Protection officer, was establishing that the burning had occurred on the same day of the shooting.

Our only real suspect was an unnamed Special Operations Division (SOD) officer who drove away in Tanner’s Chevy. And we had no evidence suggesting that whoever did that also torched it, save for Tanner’s claim about road flares, about which Ashley and I remained skeptical.

It made sense that SOD would want to move the body somewhere. Five days after Katrina, as the death toll mounted around the city, the city morgue was overwhelmed. A thousand-plus bodies remained littered across the city. The city simply lacked resources to collect the dead. It was not uncommon to drive down the street and see bodies left where they fell, covered by sheets, cardboard, or corrugated metal. In one morbid photo taken by a visiting federal agent, a Black man lay stretched out by the side of the road, wrapped up in a brown paisley rug, his stockinged feet poking outward. The only acknowledgement of his humanity was a homemade cardboard sign that read, This man died here.

Understandable, then, why SOD officers didn’t want a dead body in a car decomposing in ninety-plus-degree temperatures in front of the building they called home. But it was hard to fathom why they would burn the body, destroying the physical evidence of a fatal shooting that would fall to NOPD to investigate, particularly if they had no knowledge that the man had been shot by another cop. Even if they were aware of that, why would SOD cross the line into flagrant criminality to protect an officer they didn’t know?

Ashley and I, stuck in the car, played out classic “means, motive, and opportunity” scenarios. Sitting in front of Warren’s house, it struck me for the first time how close he lived to the levee where Glover’s body was burned—just over a mile away.

It was conceivable that somebody at the Fourth District had told Warren that the body of the man he had shot that morning had been moved from Habans to the levee. He could have found the car before darkness fell and destroyed the evidence of his crime. The time window was tight, but possible. Of all the people in the case, Warren certainly had the most motive to burn Glover’s body. As far as “means,” burning a car didn’t seem too hard to pull off, especially for a guy who, we would later learn, had a couple of engineering degrees.

It was all speculation, of course, but with little evidence and lots of time, we had seemingly endless possibilities to sort through. But by the second hour of the stakeout, we were ready to talk about something else.

Excerpted from FIRE ON THE LEVEE by Jared Fishman with Joseph Hooper. Copyright © 2023, Hanover Square Press. Reprinted with the author’s permission.