Four alumni authors consider, then dismantle, the myths that govern how we choose our careers and that keep us stuck in unhealthy patterns from childhood to retirement.

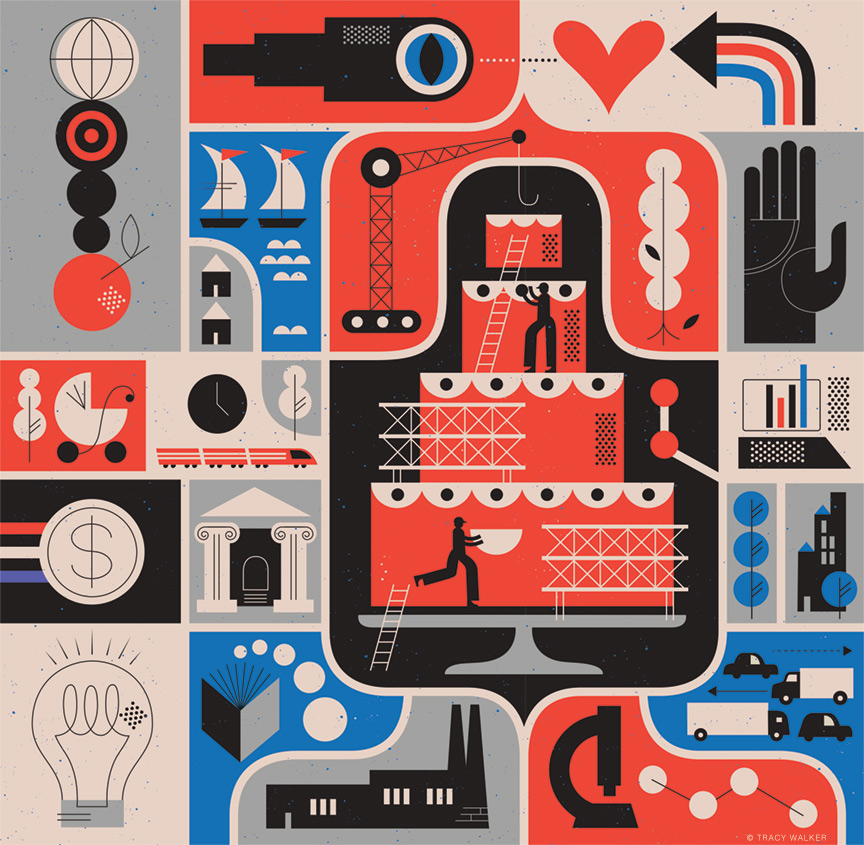

By JoAnn Greco | Illustration by Tracy Walker

Every year around this time, we take a look back in an effort to make sense of what’s ahead. We consider shedding and acquiring, ditching and adding. If I left my partner, my city, my job, would I be better off? Maybe if I got a hobby, new friends, more money, I’d be happier? We’re seeking balance, with the scales continually tipping back and forth between work (our careers, our jobs, our incomes) and life (everything else).

This quest is a perennial one, but lately we’ve entered an era of mass resignations, “quiet quitting,” and small-shop unionizing that’s brought renewed interest in what we want and expect from earning a living. “COVID was a wake-up call because people lost their work[place], and often their jobs,” says Simone Stolzoff C’13. “At the same time, they experienced a less work-centric existence where they could spend fewer hours commuting and more with their kids. They began thinking not just about what they got from their jobs but what they gave to them.”

Even before the pandemic, Stolzoff was one of those people, periodically questioning why he was so caught up with the idea of a “dream job”—a search that took him from studying poetry at Penn to marketing in Silicon Valley, then on to staff gigs at The Atlantic and the global design firm Ideo. In 2023, he released his first book, The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work. “I’d spent years trying to find my vocational soul mate,” he says, “and I learned that there are risks in looking for work to be your only source of meaning. For one thing, if you lose your job, you can find yourself asking ‘what’s left?’”

Stolzoff’s book is one of a handful by Penn alumni that aim to bust the myths that guide our attempts to hold onto—or let go of—our identities, choices, and expectations. Myths like: only losers quit, artists are bound to be unhappy, our jobs define us, and retirement is the beginning of the end. Turning to psychological research, case studies, and their own experiences, they bracingly exhort us to break free of the mental shackles that stymie us in living our best lives.

One overarching theme: we should feel free to deviate from the scripts and reinvent ourselves.

In Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away, Annie Duke Gr’92, one of the winningest women to ever play professional poker, makes a case for tossing in the cards as a smart strategy not a desperate last resort. Rachel Friedman C’03 G’07, once an aspiring violist and now a freelance journalist, turns her recurring bouts of coulda-shoulda into And Then We Grew Up. Marci Alboher C’88 who, like the others, has shifted and morphed professions through the years helps others make such transitions in The Encore Career Handbook: How to Make a Living and a Difference in the Second Half of Life. “For the 10,000 Americans who turn 65 every day, it’s become clear that the Golden Years model has broken down,” she says. “Yes, they want to rest and travel and be with their grandchildren. But they also want to stay in the game and stay relevant, and many of them need to make more money.”

The tropes they explore actually begin in childhood. “I was primed for a career in music since I was a self-motivated eight-year-old,” says Friedman. “But as I moved along the path to professionalization, I became more and more unhappy. I had a lot of anxiety about performing, I became attuned to all the ways my technique was falling short, and I hit the limit as a musician in college when I was no longer a big fish in a small pond.”

The option to jump or be pushed off such a treadmill “is a total gift,” says Duke. “It allows us to step back and ask, ‘If I were to start this thing today, knowing what I do now, would I?’” In the middle of living life we become myopic, she observes in Quit’s concluding chapter. A goal, she writes, “becomes a fixed object … the thing we’re trying to achieve, instead of all the values expressed and balanced when we originally set the goal.”

So, as we move into the new year, she and the others suggest we skip the determined objectives and the weighty expectations. Instead of focusing on the road maps we’ve convinced ourselves we need to follow in order to succeed, let’s all look harder at where it is we want to end up.

Playing Your Cards, Right

In other words, we have to play the long game. “A poker player will play thousands and thousands of hands over their lifetime,” Duke writes in Quit. “In the grand scheme of things whether or not they lose one single hand matters very little. What matters is that they’re maximizing their expected value over all those days and all those hands. That’s what they mean by one long game.”

According to Duke, this eye-on-the-prize attitude helps expert players overcome psychic obstacles. “I noticed pretty quickly when I began playing that there’s this obsession among elite players about when’s the right time to quit and how to avoid getting emotional about it,” she says. Quitting always engenders a sense of what might have been, she adds, then offers some recommendations to help determine when the time is right. They include establishing if-then “kill criteria” (If I don’t get a tenure-track position in four years then I’ll leave academia) and tempering your goals with “unless” conditions (I’m going to stay in my job unless I have to take work home more than once a week). Like any good poker player, she also encourages us to embrace both the presence of luck and the absence of control in our lives.

Duke has always made the best of the hands she’s been dealt. She grew up on the campus of New Hampshire’s tony St. Paul’s School, where her father Richard Lederer, a wordsmithing public intellectual and author of some renown, taught linguistics. Attending the school themselves, she and her siblings were steeped in the rigors of college prep and primed for the Ivies. Gambling was also in the air: Duke’s older brother Howard Lederer had been playing poker since high school, and by the time he was 23 he had earned a seat at the final table of the World Series of Poker. Joining him at some of these tournaments, Duke began trying her hand at low-stakes games.

She hit a crossroads while working toward her doctorate at Penn. After becoming severely ill with gastroparesis, she made her first decision to quit. In taking a leave from graduate school, though, she also relinquished the National Science Foundation fellowship she had earned. She needed money and Howard suggested she turn pro, offering to front her a couple grand. She grabbed the chance. “Sometimes being forced to quit gets you to see options that have been right under your nose all along in a new light,” she writes.

Now she consults to major corporations on aspects of decision-making and risk-taking, tutoring on how to remove emotion from the equation and making hay from the intersection between her two fields of expertise. “Most of the cognitive biases that you study in the behavioral sciences you see in a very explicit way at the poker table,” she says. “Things like the sunk cost fallacy where players think ‘I can’t fold now because I have too much money in the pot.’”

The book covers that and other cognitive biases that can keep us from tossing in the towel, such as self-identity (I’m not a quitter!), the endowment effect (I can’t throw in the cards; this is such an awesome hand!), loss aversion, and status quo bias. Duke takes the established science around decision-making—citing pioneers in the field like Richard Thaler and Daniel Kahneman, and referencing research from today’s thought leaders, including Penn professors Katy Milkman, a behavioral economist who specializes in choice [“Choice and Change,” Jul|Aug 2021], and Angela Duckworth Gr’06 [“Character’s Content,” May|Jun 2012], a psychologist best known for her research on the power of grit—and brings it to life through case studies often drawn from her own consulting work.

In a passage on the notion of expected value, she tells the tale of a stressed-out emergency room physician torn between her love of doctoring and the additional administrative burdens she had gradually assumed. Offered a way out via a job opportunity at an insurance company, the physician calls Duke for advice.

After listening to her story, I asked her a simple question: “Imagine it’s a year from now and you stayed in the job that you’re currently at—what’s the probability you’re going to be unhappy at the end of that year?”

She said, “I know I’m going to be unhappy, one hundred percent.”

I followed up by asking, “If it’s a year from now and you switch to this new job you’re considering, what’s the probability you’re going to be unhappy?”

She said, “Well, I’m not sure.”

“Is it one hundred percent?”

She said, “Definitely not.”

Leading the physician to declare that switching jobs “has to be better.”

“All that I had done was to reframe her quitting decision as an expected-value problem,” Duke concludes. “She realized taking the new job had the higher expected value.”

For Duke, knowing when to quit is the single most important decision-making skill we can learn. “The option to quit is the solution to the problem,” she says. “We have to make decisions all the time where we don’t have all of the information, where we may later learn something, where circumstances can change. It’s true of relationships, jobs, investments. The option to quit is an excellent way to deal with that uncertainty.”

Defining Potential

The particular uncertainties of the artist—of just how talented you are, of having your work judged, of winning gigs and, always, of paying the bills—lies at the crux of Friedman’s And Then We Grew Up, though much of what she uncovers works for other careers and aspects of life. As she tells it, those plagues led her to abandon her own idea of becoming a professional musician. After beginning a writing career and selling her first book, it seemed as if she’d found a new way to live artistically while still making a buck. It turns out that she had merely exchanged one fantasy for another.

In Grew Up, we meet her shortly after the high of that early writing success has subsided and the dark thoughts have returned. “The way I felt about writing had over time become infected with anxiety and self-doubt,” she writes. “Once again … I was flailing around in the middle of the pack.” Things come to a head at the movies one day, when she spots one of her old campmates from Interlochen, the artsy Michigan summer camp, smiling from the screen.

Friedman decides to track down some of her buddies from camp to see if anyone else had “made it.” The book is filled with their stories, yes, but as she writes, it’s also “my story of being a former musician who never fully made peace with quitting and a current writer unsure of what her future holds.” Learning of the compromises and vicissitudes faced by her peers was “tremendously helpful to me,” she says. “Some still had that sense of ‘what if,’ but most had reached a state of acceptance—they were where they were supposed to be.”

She structures the book with eight profiles that serve as lived retorts to the common wisdom that dominates our perception of the artistic life. Take Jenna, a former violin prodigy who teaches music at a Chicago high school. “If I hadn’t known her as a kid, this would have struck me as perfectly lovely,” Friedman writes of her thoughts as she watches Jenna at work. “But I’d witnessed her abundant early talent and, caught up as I was in conflicted feelings about my own potential, I couldn’t help but feel like she kind of, well, owed her talent an attempt to be the absolute best on the biggest possible stage.” She goes on to admit: “It seemed to me that people who strove for that kind of greatness weren’t well-rounded spouses and parents and high school orchestra conductors … I believed that real artists are art monsters. They choose art above all else.”

Or consider the very non-tortured Adam, who once dreamed of making films and writing plays but had found moderate success in Hollywood writing sitcoms pitched to teenage girls. “Look, I’m really ambitious,” he tells Friedman. “But I want to be a person first, and an artist second … Whether I’m talented or not is really not up for me to decide,” he continues. “I hope I am. But mostly I believe in doing the work.” Friedman finds his Zen-like practicality enviable. Apparently, she writes self-mockingly, “I had signed some grandiose, meritocratic, imaginary contract with the universe regarding my potential. As long as I put in the hours … I would achieve whatever goal I set for myself.”

Time for another look at grit, the author suggests. “When we’re told success is as simple as gritty perseverance,” she writes, “it’s a short walk to believe that failure must be all your own fault.” She enumerates her own myriad opportunities, not just the camp, but the lessons, the youth orchestras, the supportive parents and mentors (including at one point the principal violist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra): “Yet I still didn’t make it.” The simplistic distillations of Duckworth’s ideas on stick-to-itiveness don’t take into consideration factors such as luck, observes Friedman, echoing Duke and quoting from a 2017 interview with the poker player that appeared in the science magazine Nautilus.

Still, Friedman doesn’t mean for the campers’ stories to sound like cautionary tales. “I’ve had readers tell me that they gave the book to their high school daughter and I’m, like, oooof,” she says. “I think we all have to go on our journey—and there’s something beautiful about trying.” As she’s “come to peace with the notion of not being so special,” she says, “what matters most to me is finding time to work on the stuff that brings me joy. That’s what my definition of success is now.” She’s returned to two other instruments that she had played as a kid, the guitar and piano. She’s volunteering as an end-of-life doula, to support people in hospice as they prepare mentally and emotionally for death. She continues to write essays and is working on a novel.

And, she’s got a day job as managing editor for a couple of academic journals. “That’s something that’s been a really big help dealing with the financial instability of freelance writing,” she says.

Building a Self

In The Good Enough Job, Simone Stolzoff shares his own realization that while some people (and not just artists) are fortunate to love, really love, their work, it’s perfectly alright to treat your job chiefly as a way to earn cash. In fact, he adds, it can be preferable, leaving a lot more time and energy for the personal pursuits that often get short shrift from committed careerists. “We ask kids practically from the minute they can talk what they want to be when they grow up, we treat CEOs like celebrities, we plaster those ‘do what you love’ signs on the wall—and I definitely drank the Kool-Aid,” Stolzoff says. “I thought the stakes were so damn high. It wasn’t in my makeup to see any other way of self-expression other than for it to be the same vehicle that gave me my paycheck.”

The all-in, perk-filled culture of the stereotypical Silicon Valley start-up has only further fostered that mindset, he believes. “But today’s young workers have been through too many rounds of layoffs and they’re much more cynical,” Stolzoff says. “They understand that there’s no mythical work/life balance where, once you achieve it, you float in a lotus pose. It’s this wobble, this constant struggle.” That doesn’t mean he’s written a “slacker manifesto,” he adds. “I think the hours we spend at work are important and that while you’re there you should look for some aspect of meaning and adequate compensation. But when the workday is done, go home.”

The book takes its title from British psychoanalyst and pediatrician Donald Winnicott’s concept of “good enough parenting,” which exhorts parents not to lose themselves in child-rearing and encourages them to teach kids to self-soothe. Much of the thrust of Stolzoff’s book, though, looks to “self-complexity,” a term coined by Patricia Linville, a professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. “When we invest in different sides of ourselves, we’re better at dealing with setbacks,” Stolzoff writes of her findings. “If your identity is entirely tied to one aspect of who you are—whether it be your job, your net worth or your ‘success’ as a parent—one snag, even if it’s out of your control, can shatter your self-esteem.”

Like Friedman, Stolzoff divides The Good Enough Job into chapters that delve deeper into the careers of his interviewees, “workists” who metaphorically used their jobs as a source of or substitute for religion, love, actualization, friendship, and status. “I found parts of myself in all of them,” he says. “A lot of people make career decisions based on market value and then wonder if that’s all there is, others veer toward the thing they love and find themselves always worrying about paying the rent.”

In the book, he recounts a time when he was torn between two attractive job offers. “I judged myself for caring, for ascribing so much significance to the decision. But … it wasn’t just about my job; it was also about my identity. It was about how I’d answer the question ‘What do you do,’ which I took to mean ‘Who the hell are you?’” He ultimately chose the higher-paying job and came to regret it. “I was insufferable … I was a crummy friend … and a crummy worker,” he writes. But when he loosened his grip on work, returned to his hobbies and friends and focused on the positive aspects of his days at the office, he says, he “saw my job as good enough.”

One of Stolzoff’s most compelling stories is that of Fobazi, who like many a 15-year-old book-lover decided her dream job was to be a librarian. It was a big case of what she would later term “vocational awe” in a paper she wrote for a library science journal. As the piece gradually gained wider attention, the response made it clear that the affliction—which she defined as a belief that certain workplaces or professions are callings rather than jobs, and thus beyond critique when they demand long hours and offer lower salaries—plagues people like artists, chefs, ER personnel, journalists, teachers, and zookeepers.

Fobazi began speaking on the subject all over the country, became an activist for the field, and is now studying to become a professor of library science. “I no longer have a dream job,” she tells Stolzoff. “I’m going in with eyes wide open.”

Leaving a Legacy

Buried dreams don’t have to stay dead forever, though, suggests Alboher. And The Encore Career Handbook is packed with ways to resurrect them, especially if your career is over or winding down. Whereas the other three books seek to embolden us to shake things up, to shed outdated identities and burdensome myths, this book is about adding.

At the time she wrote the book 10 years ago, Alboher was a vice president of Encore.org, a nonprofit dedicated to “helping people pursue second acts for the greater good.” She still works for the organization, though it’s now called CoGenerate and has shifted its focus to bridging the gap between generations so they can combine talents for “mutual benefit and collective action.” People who are just starting out in their careers and those who are easing out of them have “interesting psychographic parallels,” Alboher says. “They’re each seeking to clarify their identities.” Whether a kid is graduating and entering the job market, or his mom is the one going to college to study for a new kind of work, “they should be looking at each other’s LinkedIn contacts,” she jokes.

Alboher terms herself a late bloomer. “I became a lawyer to please my parents. They were so proud that I went to an Ivy League school and became really wrapped up in me getting a professional degree,” she says. “I didn’t have a good sense of what I wanted to do and fell into this mindset of finding a job and financially taking care of myself.” She ended up in law school but had trouble finding the right job fit and left the field for good after eight years. Like Friedman and Stolzoff, she turned to freelance journalism. A specialization in work and career trends led to a column, Shifting Careers, in the New York Times and eventually to Encore, where she accepted a full-time position so she “could shape the future of work, and not just write about it.”

Her first project was to write the handbook. It too looks at the huge chunk that work occupies in our psyche and encourages readers to disengage and examine that role more closely to figure out if you need a change. Chapters —filled with a mix of quizzes, short profiles, FAQs, resource boxes, and reportage—address honest self-assessment, comfort with uncertainty, money needs, networking, self-presentation, skill-building, and entrepreneurship. Although the exercises are applicable for all older adults trying to figure out what to do with themselves for a second or third act, the emphasis is on finding a way to make an impact. “For many it may finally be time to play the flute or open an artisanal bakery,” Alboher writes. “[But] there is also a compelling urge at midlife to make a mark in a way that leaves things a little better for future generations.”

This feeling kicks in both for people who have never thought of themselves as do-gooders as well as those who have worked their whole lives in the helping professions or for nonprofits. “Some have this sense instinctually, but others feel they want to be more intentional,” Alboher says. “It comes from developmental psychology and what Erik Erikson called ‘generativity,’ which he contrasted with stagnation. People who find it tend to feel more life satisfaction.”

When you fluidly change and blend layers of career identities, Alboher says, “everything you’ve done is useful. You’re building a foundation and bringing old skills into new jobs.” In the wedding cake of life, whether you think of its components—what you do for money, for creativity, for passion, and for community—as ingredients to be combined, separated, or judiciously sprinkled throughout, is entirely up to you.

JoAnn Greco is a frequent contributor to the Gazette.