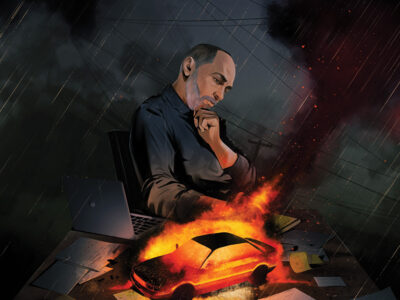

On September 8, 1992, a suburban Maryland woman named Pamela Basu was driving her 22-month-old daughter to preschool when two men approached her BMW as she sat at a stop sign. The crime that followed was grisly. Basu was forcibly pulled from the car, but on the way out her arm became entangled in her seatbelt.

As the men sped away, they dragged Basu along with them, killing her and leaving a crimson trail through the streets that ended only when the men crashed two miles later.

Basu’s story quickly became national news. Headlines warned of a new “Terror on Wheels” and declared the hijacking of cars—or carjacking, as the rebranded crime was coming to be known—to be “epidemic” in America. As the frenzy escalated, it did not seem to matter that statistically speaking, carjackings were no more or less common than they’d ever been, or that armed robberies accounted for a scant fraction of all automotive thefts in the country.

The following year the Pennsylvania legislature responded to the panic. On June 23 it passed an amendment that added “Robbery of a motor vehicle” to the state’s criminal code, classifying it as a first-degree felony punishable by 10 to 20 years in jail. While there was reason to doubt whether new legislation could stop an old crime, the bill at least conveyed that Pennsylvania’s elected leaders were addressing the concerns of their citizens.

The first problem with the amendment was that it wasn’t needed. “It’s not as though there was some gap in the law or that carjacking hadn’t been done before,” says Paul Robinson, the Colin S. Diver Professor of Law and a former federal prosecutor. He notes that carjacking was already addressed under existing robbery statutes and that such redundancies have a downside. “There are real costs,” he continues, “in creating unnecessary and overlapping offenses that make the law more complicated.”

Carjacking aside, legislative haste has resulted in inconsistencies in the law that border on the farcical. Keeping an adult as a slave is treated as equivalent to assaulting a sports official (they’re both first-degree misdemeanors). Reading someone’s email without permission is a third-degree felony punishable by up to seven years in jail (thanks to the imprecise wording of an electronic-surveillance statute).

Robinson has worked on criminal codification projects in places ranging from Kentucky to the Maldives, and Pennsylvania is his latest focus. This past semester he led the law school’s Criminal Law Research Group (CLRG) in a systematic review of the state’s criminal code. Their aim was to identify places where the law has become “degraded” by legislative hyperactivity, and after several months of work they’d found no shortage of examples. On December 15 Robinson traveled to Harrisburg to present the CLRG’s report to a joint session of the state’s House and Senate judiciary committees, in what he hopes will be a first step towards reforming the way that Pennsylvania delineates crime.

The core of the current Pennsylvania code dates to 1972, when the state replaced its convoluted common law with what is known as the “Model Penal Code,” written 10 years earlier by the American Law Institute in order to show state governments what a rational, internally consistent criminal law would look like if written from scratch. At the time of its adoption the new Pennsylvania code was striking in its efficiency. In only 282 provisions, it managed to capture just about all the ways that one might do wrong by society.

Since then, though, political gravity has set in. Between 1972 and last year the number of offenses in the code more than doubled, which is to say nothing of the 1,600 additional crimes that have been added to statutes outside the criminal code. What’s worse, the trend is escalating. The CLRG report found that legislative activity now adds upwards of 30 new crimes a year to the code. Robinson described one legislator as being “shocked” when confronted with the numbers.

There are several explanations for the increase. It owes in part to what Robinson calls the “crime du jour” phenomenon underlying both the carjacking law and a 2002 amendment that criminalized paintball gun offenses following what one judge referred to as “paintball sprees” targeting homes and cars. (This despite the fact that vandalism and assault laws already criminalized the crimes in question.)

In other areas, interest group politics would seem to be at work. The theft of $175 of property from an individual puts a perpetrator on the hook for a maximum of two years in jail, while stealing the same amount of merchandise from a store can net five. Stewart Greenleaf C’61, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, says that lobbyists were “seldom” behind amendments to the criminal code. Robinson, however, attributes the discrepancy in theft statutes to the efforts of the state retailers’ association.

Other suggestions of influence are evident in special laws protecting agriculture, several of which are featured in the CLRG report. In 1998 legislators made agricultural trespassing a more serious crime than general trespassing; and while spray painting a car is prosecuted as criminal mischief, since 1988 doing the same to a tractor has been considered agricultural vandalism and punished four times as severely.

Such clutter would be merely annoying if it led only to increased printing costs. But the ad-hoc expansion of the code has created problems that ripple throughout the criminal justice system. When new crimes are legislated, Greenleaf explains, lawmakers typically fail to situate them “in context with the rest of the criminal code.” And without a requirement to square new punishments with existing ones, political calculations like wanting to look tough on crime almost always impel more jail time rather than less.

“[Legislators] get hot and bothered about one particular offense and there’s an easy tendency to exaggerate just how serious it is,” says Robinson. “They never ask the question, What is the appropriate grade for this new offense compared to existing offenses?”

A prime example of this dynamic is the 1997 Crimes Against the Unborn Act, or fetal-homicide law, cited in the CLRG report. The bill was deeply embroiled in abortion politics and made it a super grade felony (above first-degree) if a fetus dies during an assault on a pregnant woman. The punishment was set at mandatory life in prison, which exceeded sentencing guidelines for third-degree murder, rape, and kidnapping.

In order to measure how well the state criminal code aligns with Pennsylvanians’ intuitive sense of justice, the CLRG asked a sampling of residents to place hypothetical crimes on the state’s criminal offense scale. Asked to determine the punishment for “deleting non-valuable data from someone’s computer without their permission,” respondents felt that a maximum of 90 days in jail was enough, while current law prescribes up to 7 years. And while residents thought that “a pawn shop owner buying a stereo that he knows is stolen, intending to sell it” was roughly equivalent to the theft of property valued between $50 and $200 (second-degree misdemeanor, two years), the state’s criminal code rates it a first-degree felony and recommends up to 20 years in jail.

“When the criminal law imposes punishments that don’t comport with people’s sense of fairness, you lose support for the law itself,” says Matt Majarian, a second-year law student in the CLRG. He cites a host of externalities that develop as a result, including vigilantism, unwillingness to serve on juries, and reluctance to report crimes to the police.

While many of the consequences of a wayward penal code are hard to quantify, one is not. In 2009 the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections spent $1.6 billion to incarcerate a prisoner population that is growing by almost 10 percent a year. “If the legislature’s response to an egregious crime is to raise the offense and if that’s not done in perspective,” says Greenleaf, the judiciary chair, “it can create the situation we have now where we’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars just to build new prisons.”

For his part, Robinson left the December hearing convinced that the CLRG’s case had been heard, and he hopes that the group’s report will make it easier for politicians to mobilize the public behind reform. He remains ambivalent, however, about the likelihood that progress will originate in Harrisburg. “It may require more grassroots grumbling and complaining first,” he says. “It’s not clear to legislators that there’s a reason they should invest political capital in making changes come about.”

—Kevin Hartnett