To mark the Netter Center’s 30th anniversary, founding director Ira Harkavy C’70 Gr’79 trumpets the past and the future of Penn’s strategies to revitalize West Philadelphia—and alumni return to campus to tout Harkavy as an inspiration in the field of university–community engagement.

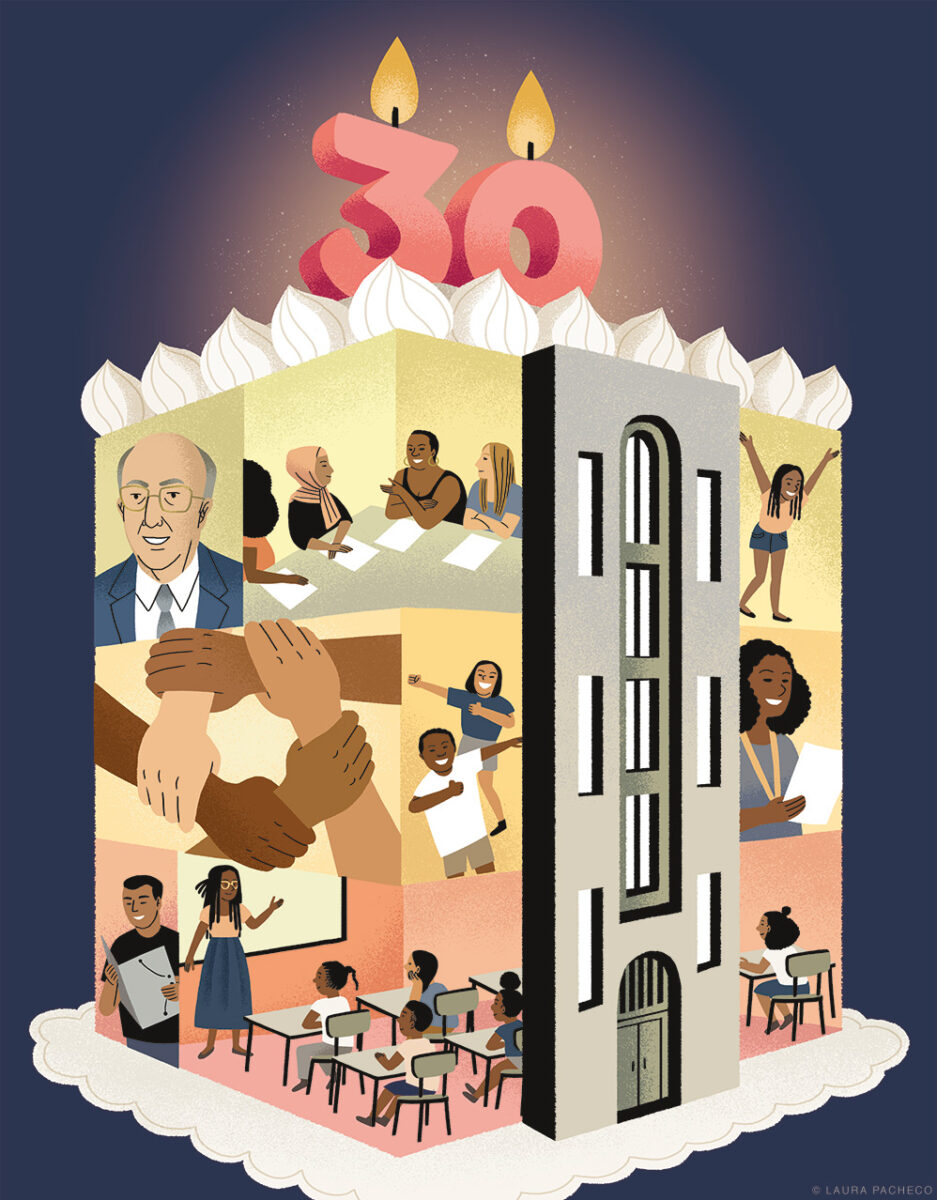

By Dave Zeitlin | Illustration by Laura Pacheco

Fifty-four years after his impassioned speech during a College Hall sit-in altered the trajectory of the University’s relationship with its West Philadelphia neighbors, Ira Harkavy C’70 Gr’79 stood in front of a smaller group, in a smaller space on campus, bearing a humbler message.

“I am moved beyond measure,” Harkavy said. “I’m not usually at a loss for words. I think this may be one of the first times that I am.”

Inside the same Irvine Auditorium room sat a dozen Penn alumni whose lives had been shaped by the Barbara and Edward Netter Center for Community Partnerships, the University’s primary vehicle for advocating civic and community engagement of which Harkavy is the founding director. The Netter Center marked its 30th anniversary with a full calendar of events throughout the 2022–23 academic year, including a mid-April Alumni Community Engaged Scholarship Symposium featuring those 12 speakers who credited Harkavy with inspiring them to pursue their own careers in community-engaged research, teaching, and learning.

About three weeks later, during Alumni Weekend, other alumni spoke about their Netter Center memories following a question-and-answer session with Harkavy and new Penn Provost John L. Jackson Jr. at an event called “Changing Universities to Change the World.”

Below is the conversation between Harkavy and Jackson, edited for space and clarity, followed by highlights of the April alumni symposium. Jackson opened the discussion by asking Harkavy to trace his trajectory from the 1969 College Hall protest he led—during which he said, per reporting in the Gazette’s March 1969 issue, “It’s true this University is committed to social change, but social change for whom and to what?”—to the 1992 establishment of the Center for Community Partnerships (to which the name Netter was added in 2007 following a gift from Edward Netter C’53 and his wife Barbara).

“CHANGING UNIVERSITIES TO CHANGE THE WORLD”

IRA HARKAVY: 1969 was a year of tremendous protest, focusing on issues related to civil rights, anti-racism, the anti-war movement. I led a large protest in College Hall, focusing in part on the war but largely on Penn’s treatment toward the West Philadelphia community. It was a peaceful protest, it was a successful protest, and it set a stage for conversations. There was a recognition that Penn and this community needed to work together.

The early ’70s was a period of significant protests, but in terms of the University of Pennsylvania there became a decrease in the focus on West Philadelphia. That was partly because Penn was facing tremendous economic difficulties. I used to teach with former President Martin Meyerson [Hon’70], and he said to me that he went to the faculty to push some of these issues about West Philadelphia because he was an urbanist. But there was not the ability to carry that idea forward.

In the 1980s Sheldon Hackney became president, and issues of civil rights and racism were central to his writing, his experience. Sheldon helped Penn turn to an orientation that said, in an institutional report, that Penn and West Philadelphia’s futures are intertwined. That was his signal statement: as Penn went, so would the community. And he began to turn the institution forward.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s there had been increasing recognition of the environmental crisis, and deterioration in the community that was becoming sharper. There was a sense—and I wrote this at the time—that universities cannot afford to be islands of affluence in seas of poverty. That began to be felt and began to be experienced by the institution.

It was in that context that the Netter Center was born. It had three propositions as founding principles. The first was exactly what Sheldon had said: universities and their communities, Penn and West Philadelphia, are intertwined. Secondly, Penn could do a great deal to improve the quality of life in the community, as the largest employer, largest purchaser of goods and services, and largest landholder. But most importantly, we had students—idealistic, creative, caring students—and faculty and staff who are crucial to improving the quality of life in the city. The third proposition is what made Netter unique: that this work wasn’t just for the community, but it was mutually beneficial. It was the idea that Penn would be a greater research university, that Penn would make greater contributions to knowledge, that Penn would be better able to educate students for creative, caring citizenship, and that Penn would be more effective in developing not just better citizens but in fact lifelong contributors to a democratic society.

So the idea of a mutual benefit to Penn [engaging with] the community—this was an institutional advancement strategy in effect. And finally, if you’re going to do this, you can’t bring change just in Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, and Penn; you need to in fact, share those ideas and spread them to the rest of the country and around the world.

JACKSON: So much change, right? You’ve marked some of the regime change in the university. Throughout all this time, the Netter Center’s mission has been clear. And you have to make sure the mission continues to move forward. Can you tell us about the core strategies you’ve used over the years to make sure the mission both continues to resonate and moves forward?

HARKAVY: I appreciate that question because the issue isn’t the vision; the key question is how do you do it? That’s the hard real world and intellectual question. That’s how you make greater contributions to knowledge. We’ve had a few principles.

The first principle is the idea of having credit-bearing academic courses in which students and faculty work with the community to improve the quality of life … and focus on what might be termed universal problems, such as poverty, social justice, poor schooling, inequality in healthcare. Currently, I think we have upwards of 70 academically based community service [ABCS] courses—from physics, to philosophy, to math, to music … that are simultaneously making a difference on campus and in the world.

The second strategy is university-assisted community schools. The idea is that the school is a hub of a neighborhood and also a place in which young people learn through engagement and solving the problems of their environment, those universal problems as they manifest in their community. In a university-assisted community school, the university is a leading partner.

The last point is you can’t bring about change unless you aggregate multiple activities and efforts. Having separate programs doesn’t do much when they’re all isolated, siloed. When Penn aggregates those ABCS courses—those 70 courses with about 1,800 students, plus 1,200 volunteers, work-study students—and brings its resources to university-assisted community schools, it can have an actual impact.

JACKSON: I will say as someone who has participated in ABCS courses, it also clearly demands a mutuality between the community and the university, between the academics and the students.

HARKAVY: That’s exactly right. The idea is that it’s not done in the community—it’s done with, and it’s done for. You’re learning with them. They’re your neighbors. It’s not done for the research project, [though] that can be part of it. The bottom line, as you said, is they are our partners.

JACKSON: Along with the ABCS courses, also at the Netter Center there’s been the organizing principle for thinking about “community-engaged scholarship” writ large. You convened a group of senior scholars from all around campus to think deeply about that question. What does it entail? How do we make sure it counts? How does it transform intellectual knowledge production? I was fortunate enough to be a part of the conversation led by [Professor of Education] Matt Hartley. Can you give us a sense of what examples of community-engaged scholarship look like?

HARKAVY: Community-engaged scholarship is growing at Penn and around the country. It’s this idea of working with the community in partnership and working deeply locally. ABCS courses capture that idea. They represent, in a certain sense, the quintessential form of community-engaged scholarship. I’ll give an example: a colleague of ours, Herman Beavers [Penn’s Julie Beren Platt and Marc E. Platt President’s Distinguished Professor of English and Africana Studies], developed a course ten and a half years ago, working with the Paul Robeson House & Museum, which is a great cultural institution in West Philadelphia, engaging with the work of August Wilson, a great playwright who focused on Pittsburgh. This is West Philadelphia. How does that relate to us? Working with adults, students write their own plays. They design their own approaches to how to think about August Wilson. They take their experience and become the characters in the play. And then those plays are performed to the community. I’ve had the good fortune of watching and learning and seeing the powerful impacts.

Lori Flanagan-Cato, [an associate professor in Penn’s psychology department], teaches a course called The ABCs of Neuroscience, which teaches students at Paul Robeson High School neuroscience by having the Penn students teach them what they’re learning in class. The best way to learn is to teach. These students in fact teach students in West Philadelphia who would have never had the opportunity to learn neuroscience. Lori’s class this year received an extraordinary accolade. The principal of the school looked at the data, which is reported citywide, [and found] that the school had the greatest single increase of any school in Philadelphia in three straight Keystone tests. And the principal indicated the most important contributor to that change was Lori Flanagan-Cato’s course. That’s community-engaged scholarship, powerfully seen.

JACKSON: We’ve talked a lot about the relationship between Netter, Penn, and the local community. But I also know that Netter has a national and global impact. Tell us about the reach of Netter.

HARKAVY: When we were founded, the idea was that you can’t bring change just here. How do you have this work spread so that it influences you at home and influences others? We’ve seen the reach very recently. One of our 30th anniversary events was a symposium with 12 graduates of the University of Pennsylvania, who did this work largely as undergraduates, who now are distinguished academics—from epidemiology, to business, to a Pulitzer Prize winner—who testified how this was transformative in their work. That is the reach of reaches: where others spread the word and teach others. And it was profound. [See part two of this story.]

In terms of organizational activities, the first thing is spreading university-assisted community schools. Every third year, we fund a regional training center that develops and spreads university-assisted community schools. Most recently it was UCLA, which did the training for the entire state of California on community school development. Now it’s the University of Binghamton [providing technical assistance across New York and New Jersey].

I also founded an organization called the Anchor Institutions Task Force: a network of 1,000 individuals across the world, focusing on universities as anchors in their neighborhood—not just being there but the principles that they stand for, [including] democratic practice, social justice and equity, mutual transformation, and place-based engagement.

The third network is one that goes back the longest, the Philadelphia Higher Education Network for Neighborhood Development that I founded in 1987. It has 25 local institutions doing the work.

And finally, we’ve been working with [several international organizations] to spread the kind of work that Netter does here in West Philadelphia to institutions and groups all over the world. The notion is that every university, not just in the United States, should work with its local community to improve democracy and the quality of life in its environment and the quality of research, teaching, and learning.

JACKSON: Where do you see Penn, West Philadelphia, over the next 5, 10, 30 years?

HARKAVY: The very simple answer is more, deeper, better. We have 70 ABCS courses; we should be up to 100. We have 16 proposals coming up this year from 13 standing faculty. And so, we want more, we want it better, we want greater impact on the students in the community. The same for university-assisted community schools. We work with eight schools in West Philadelphia; we want to expand that significantly and we want to do it better. We want to integrate the services better. We want to bring more health resources with Children’s Hospital and with the Perelman Center. We want to build that and make it stronger. The same with the law school.

I’m also looking at getting alums more engaged. Alums have been crucial. In the more difficult days, when this was not necessarily heralded by every leader of the institution … it was alums who kept this moving, along with students meeting with faculty, saying this is good and important work.

And if we do this, I am convinced it will have profound impacts on Penn’s leadership as really the greatest research university in the world. This kind of focus will, in fact, increase Penn’s impact on its students, on its contributions to knowledge. It will enable us to better advance knowledge for the continuous improvement of human life. It will enable us to simultaneously educate students to be more effective, empathetic, engaged citizens of democracy. And it will make a greater contribution to creating a true beloved community with Penn in West Philadelphia.

“WALKING IN IRA’S FOOTSTEPS”

“What would my life have been like if I hadn’t discovered what is now the Netter Center?”

Salamishah Tillet C’96 G’04 posed the counterfactual during the Netter Center’s 30th Anniversary Alumni Symposium on Community-Engaged Scholarship at Irvine Auditorium on April 20.

“Thinking about the University as a place of social justice in terms of student protest [is an idea] I think we’re all familiar with, whether it’s the 1960s, the 1970s, and most recently with the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements of today,” continued Tillet, now a professor at Rutgers University–Newark and a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer for her New York Times essays on race in popular culture. “What I didn’t know, though, was that the University itself could be [not just a site of] activism but could actually be a good neighbor and could be a source of social change in the neighborhood in which it lives.”

Tillet, like other alumni who returned to campus to take part in panel discussions, said her initial foray into community engagement mostly came from joining the Netter Center as an undergraduate, which involved taking Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) courses and volunteering at nearby Philadelphia public schools. Tillet recalled waking up early on Saturday morning, and taking the trolley to the old Turner Middle School at 59th and Baltimore to teach African American history. “Because I continued to be a teacher, I think it’s really important to know that the first time I felt like I could share my knowledge with another group of people younger than me was because of this opportunity,” said Tillet, who previously served on the Penn faculty as an English professor and is the cofounder of A Long Walk Home, an arts organization that seeks to empower young people to end violence against girls and women [“Salamishah Tillet’s Journey,” Sep|Oct 2014].

Taking trolleys and teaching at Turner is a bond shared by several of the Netter Center alumni who spoke at the event—and an experience that was equal parts eye-opening and joyful. Kim Van Naarden Braun C’95 said she helped develop a nutrition chemistry curriculum for the Turner students, recalling with a smile the “backpack full of Bunsen burners on SEPTA” that in hindsight perhaps “wasn’t the best choice.” But it did prove instrumental in crafting her senior thesis on adolescent obesity, in which she compared the nutrition of Turner students to students at a more well-to-do suburban middle school—and launched her toward a career as a senior scientific director at Bristol Myers Squibb. One of the only non-academics on the panels, Van Naarden Braun noted that Harkavy’s “influences have stayed with me over the past 30 years as a scientist and as a citizen.”

For Jeff Camarillo C’01, teaching world history and Spanish at Turner as part of a Netter Center summer internship program was “transformative” because it had been drilled into him during his pre-freshman orientation that “West Philly was dangerous and off-limits to Penn undergraduates.” But as a 19-year-old in the summer before his sophomore year, he quickly found that to be a “distorted depiction,” enjoying the “cultural vibrancy” west of 41st Street. “There was so much more for me to learn at 59th and Baltimore about democracy, community, society, justice, and equity than there ever was at 34th and Walnut,” Camarillo said. “Teaching and learning from and with vibrant young people was and still is the most gratifying, joyful, and transformational part of my life.”

Twenty-five years later, Camarillo works as an assistant director of the Stanford Teacher Education Program, where he prepares future educators to teach about racial justice in historically marginalized communities of color. “The seeds that were planted in me at the age of 19 as a rising Penn sophomore have now blossomed into a flourishing forest of critical hope and community-centered educational freedom dreams,” he said. “There’s rarely a day that passes where the learning and values instilled in me through my work as an undergraduate at the Netter Center do not make their way into my educational practice and leadership.”

Margo Shea C’95 fondly recalled taking Turner middle schoolers ice skating as part of their PE class. But the true “game changer” of her undergraduate experience came when her friend and freshman dormmate Tyrone “Bear” Robertson was murdered while back home in Chester, Pennsylvania, during winter break. Spurred by the tragedy, and a dawning awareness of urban inequality, she became an urban studies major and registered for one of Harkavy’s year-long courses. “He would walk into class staggering under hundreds of pieces of paper, all going in different directions,” Shea said of Harkavy with a smile, adding that “he invited us to be curious, to make connections, to be critical but to always be constructive, to always orient toward possibility.”

Shea has kept those lessons in mind through her own career in academia, most recently as a history professor at Salem State University, where she said she also runs an internship program that’s placed 150 students in non-profit organizations. “I’m at the most diverse institution in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” she said. “My students are first-generation, my students are veterans, my students have very complicated lives. … I help my students learn to tell their stories. Even in ways that are small, I am walking in Ira’s footsteps and I am carrying everything I learned at this institution with me.”

Bernice Garnett C’05 has been trying to recreate her own version of the Netter Center at Vermont’s College of Education and Social Services, where she is a professor and public health prevention scientist. Garnett connects her collegiate students with underprivileged counterparts in the Burlington School District. “Because I work in a very rural, white state that has pockets of deep internalized racism … I fundamentally believe in the importance of institutions of higher education no longer engaging in symbolic community-engaged scholarship but really transformative [scholarship],” she said. “I’m grateful to have had an opportunity to learn at this institution, but more importantly for the Netter Center to bake academically based community service courses into the undergraduate experience.”

When former Penn professor Richard Pepino asked a question about how to measure tangible progress in local communities involved in university ABCS courses (which he used to teach at Penn—“the greatest thing I’ve ever done”), Garnett had a thoughtful response. “ABCS courses have the potential to damage communities, actually, if we don’t have sustained commitment to social transformation,” she said. “But we are in year seven of our community partnership, so we are partners that are there and that keep showing up. They are my number one priority, at the expense of my academic productivity—and it has to be clear that this has to be at the expense of our own ego in the academic institution.”

Tamara Dubowitz C’96 G’00, a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation, was even warier in response to Pepino’s query. “I’m not sure that ABCS classes can really change communities,” Dubowitz said, joking that Harkavy might want to yell at her for that. “But I think that they can change an individual’s approach to how social change can happen,” adding that “ABCS classes changed my life for sure as an undergraduate.”

Dubowitz did make a lasting contribution to the Netter Center, writing the grant to start what is now the Agatston Urban Nutrition Initiative, a program created more than 30 years ago to help build and sustain healthy communities by promoting nutrition education, food access and sovereignty, and physical fitness in West Philadelphia.

Andrew Zitcer C’00 GCP’04 CGS’07 WEv’07 WEv’08, a professor and director of the urban strategy graduate program at Drexel University, made an enduring contribution to the Netter Center, too. He brought with him to Irvine an old T-shirt for the Foundation Community Arts Initiative, which was formed in a building near 40th and Walnut Streets that the University had purchased, and Zitcer helped hatch a revitalization plan for it during a 1998 urban studies seminar that he took with Harkavy and the late Lee Benson [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2005]. It was initially envisioned as a jazz club, but under Zitcer’s leadership the Foundation began programming varied music and cultural offerings to unite diverse groups of people. “And I’m proud to say that 25 years later, the Foundation Community Arts Initiative, now known as the Rotunda, is still in operation and presents dozens, if not hundreds, of cultural events across a calendar of incredible diversity—free and open to the public,” he said.

“It was a true watershed in my life in terms of thinking about art and community,” Zitcer continued. “It really instilled in me that arts and culture is a critical ingredient in every community transformation.”

Ira is a truly great professor that makes Penn a truly great institution.