For 40 years, Mariette Pathy Allen GFA’65 has focused her camera on gender identity and expressions of gender. Through portraits of men who identified as crossdressers in the 1980s—and later, through photos of the transgender community and trans rights movement—she has shined a light on people who were often pushed to the margins of society. Some consider her the unofficial photographer of transgender life. But finding her place in the fine art world has been another story.

BY MOLLY PETRILLA

Photos and caption information courtesy of Mariette Pathy Allen

In 1978, Mariette Pathy Allen GFA’65 and her husband Ken went to New Orleans for Mardi Gras.

On the last morning of their trip, Ken woke up early, put on his homemade jester costume, and took off for the closest parade. But Mariette was too sleepy to join him. She made her way downstairs a little later, her two cameras and assorted photo gear in tow.

She’d been working as a photographer since finishing her MFA at Penn, snapping pictures of 30th Street Station, of suburban New Jersey, of antique shops and billboards and artists and pig farmers. In those days, wherever she went, her camera bag usually came, too.

Noticing that she was alone in the hotel dining room, a group nearby asked if she’d like to join them. They were a glamorous bunch, especially for breakfast time: full make-up, evening gowns, luscious wigs, glossy jewelry.

“I didn’t have a word for it at the time, but I hadn’t seen people quite like them before,” Allen remembers. “I just thought, these are amazing-looking people.”

Soon the group headed outside to the hotel pool, circling it and then lining up shoulder to shoulder beside it. Allen followed.

She watched as one person pulled out a camera and started taking pictures of the group. Allen still had her photography bag with her. An introverted kid who had only recently outgrown her shyness, she wondered whether anyone would mind if she took a picture, too.

With some hesitation, she raised the viewfinder to her eye. Through it, she saw a group that was giddy and distracted, everyone looking in different directions, talking, laughing. But one person stared straight back into Allen’s lens.

“I had an astonishing feeling,” she says. “I felt like I wasn’t looking at a man or a woman, but somehow at the essence of a human being. I said to myself, ‘I have to have this person in my life.’”

That’s how Allen met Vicky West, who turned out to live just 20 blocks away from her in Manhattan. “And it was through meeting that one person,” Allen says, “that I entered this whole world.”

Forty years later, Allen rummages through a closet in her Upper West Side apartment. The shelves hold extra copies of her four photography books, published in 1989, 2003, 2014, and 2017.

Each book contains photo after photo of people who are transgender or who express themselves outside the limits of the male-female gender binary—starting with men who identified as crossdressers in the 1980s (including a few people from the Mardi Gras group), continuing with trans men and women in the US and Cuba, and ending with genderfluid spirit mediums from Burma and Thailand.

Allen pulls out a copy of each heavy book and heads back down the hall, past a wall-sized collage from her Penn days and into her sunken living room. Amid the room’s glossy wood floors and views of Riverside Park and the Hudson River, she settles into a chair. Her hair is neatly styled except for a single rogue strand. An aqua blouse intensifies the blue of her eyes. Two large abstract paintings she made shortly after graduating from Penn hang to her left and right, and prints from her third book, TransCuba, decorate the wall behind her.

She sits down carefully, a little stiffness in each movement, and starts to talk about two years after Mardi Gras, when Vicky West invited her to Fantasia Fair in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Vicky had brought her to a few parties and clubs by then, but nothing like the 10-day gathering in Cape Cod that now calls itself “the longest-running annual event in the trans world.” In those days, there were workshops on wigs, makeup, and scarf-tying; all-night pajama parties; volleyball tournaments with more than a few participants in heels.

“Fantasia Fair wasn’t just a cross-dresser convention—it was THE cross-dresser convention,” the Fair’s website notes of 1980, the first year Allen attended. “In these early years, the Fair served as a model for transgender events all over the world.”

In spite of the gathering’s joyous tone, not everyone was happy to see Allen and her camera there. One of the organizers chided her for not writing to introduce herself in advance. Another person threatened to smash Allen’s camera if she took their picture. But others welcomed her into their experience, laying out their own stories and showing her around the event.

She returned the next year, 1981, as Fantasia Fair’s official photographer.

“That’s when I started to learn how to photograph crossdressers,” Allen says. “I figured out how to make them comfortable, how to make them take up space in more interesting ways, how to help them connect with the femininity they felt inside.

“I was always trying to make it playful and fun,” she continues, “but often it was a very moving experience for me and for them. They had never been photographed before by someone who accepted them and appreciated them and encouraged them.”

As she continued to take pictures of people who identified as crossdressers over the next decade, Allen used her work to document their everyday lives: hugging their wives, playing with their kids, washing dishes, putting on mascara. To Allen, it was never about shock value or exploitation.

“I was determined,” she later wrote in an essay, “to change the way crossdressers saw themselves, and how they were seen by others.”

Today the difference between a crossdresser and a trans man or woman is clear. But when Transformations came out in 1989, “transgender” hadn’t yet become a mainstream term and the idea of transitioning was still so taboo that for some, it felt safer to say they were simply crossdressing.

“Not that all crossdressers identify as transgender,” adds Erin Cross, director of Penn’s LGBT Center. “But that language wasn’t even there. So Mariette created a visual language, which is so powerful.”

Over the next 10 years, Allen’s collection of photos grew until there was enough to fill a book. She typed up each person’s story and included written profiles along with her pictures. Then she started contacting publishers. She tried almost 50 before finding one who would take on Transformations.

Now, sitting in her apartment, she picks up a copy of the book.

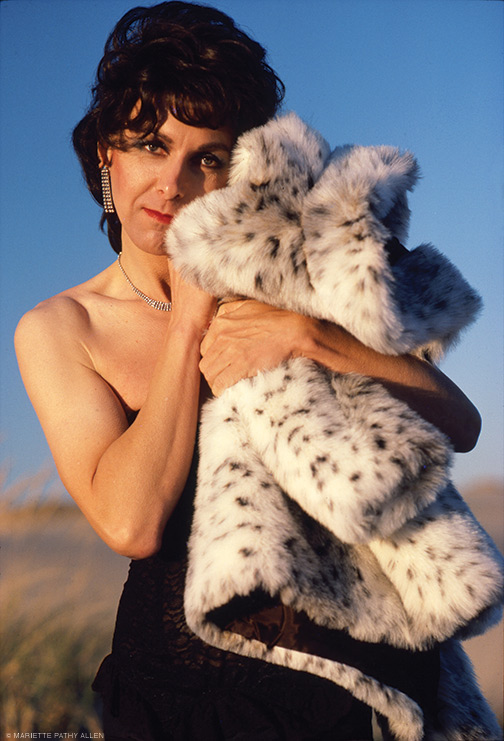

“Valerie and I were up in the dunes in Provincetown,” she says, looking at a vertical portrait. “She wanted glamor pictures. We’d been doing that all afternoon. Then it was starting to get cold and suddenly I found her hugging her fur jacket. It occurred to me that she looked like a child with her teddy bear.”

“What a beautiful child who accepts her father,” she says, pointing to another picture. It shows a young girl, about 8 years old, embracing her dad, who looks a lot like Princess Diana. Their side-by-side heads and clasped arms form a heart shape.

Allen says that when Transformations came out in print, the people featured in it were thrilled. Many even signed each other’s copies next to their own pictures, yearbook-style.

“Up until then, the only materials they could find were either in porn shops or they were scientific discussions,” she says. “Many told me it was the first time they saw pictures of people who represented who they are.”

“Back then, it was very avant-garde to portray folks who were so outside the norm,” Cross explains. “But she really humanized them and helped document a community that otherwise would have been invisible.”

Several decades later, Zackary Drucker, a producer on the Amazon series Transparent, brought copies of Transformations to the set and shared them with the creative team. At the time, they were working on flashback scenes of the main character, a trans woman named Maura (played by Jeffrey Tambor), attending a crossdressing retreat in the early 1990s. (“We are crossdressers, but we’re still men!” one attendee, angry that a friend has transitioned, tells Maura.)

Drucker says that Allen’s book showed the Transparent team how self-identified crossdressers were styling themselves around that time: what they wore, how they did their makeup and hair, and—through Allen’s interviews—how they talked about themselves and their experiences.

“For me, as a millennial trans person who didn’t experience the ’70s and ’80s, Mariette is crucial to helping me locate my own history,” Drucker adds.

But since the beginning of what Allen now considers her “Gender Series,” the art world has been less enthusiastic. After Transformations came out, she recalls a mix of outright negativity and condescending comments about her work being some kind of self-sacrifice. It was the beginning of her long battle for recognition in the fine art world—and an extension of the years she had already spent feeling like an outsider.

The only child of wealthy Hungarian immigrants, Allen sums up her childhood in two words: miserable and uncomfortable.

“I was between two worlds: the European, old-fashioned, conservative world of my parents and the very contemporary and progressive school that I went to where people called their teachers by their first names and kids wore blue jeans to school while I went in there carrying a pocketbook,” she says.

Whether she was at Manhattan’s exclusive Dalton School or at home, Allen felt out of place. “I had very few friends and was extremely shy—that lingered for a long time,” she says.

Painting provided some of the only moments that she felt at ease. She didn’t have to talk to anyone or wear the right thing.

She studied art history at Vassar and then enrolled at Penn as an MFA student in painting. Allen remembers those years at Penn as some of the happiest in her life.

At the time, the Fine Arts Library housed all the studios and classrooms for her concentration and its cousins: printmaking, sculpture, architecture, landscape architecture. The program encouraged its artists to learn from each other. If Louis Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71 gave a lecture to the architecture students, the painting classes went, too. If high-profile painters came in to critique student work, the architecture students sat in. “The whole thing was an ecstatic experience,” Allen says.

As graduation loomed, a University photographer came in to snap pictures of the students at work. On his way out, he invited Allen to a class that he was taking downtown. She figured, why not?

The instructor was Harold Feinstein, a fine art photographer best known for his black-and-white images of Coney Island from the 1950s. “I went to this class and I had such an interesting time that I thought, ‘I’ll just take pictures,’” Allen remembers.

She set up a darkroom in her Philadelphia apartment and began booking job after job.

“Photography is a passport into the world—you can go anywhere and do anything,” she says. Suddenly, the shy, uncomfortable kid didn’t feel so shy anymore. “Once you have the camera in your hand and a project in your mind, it’s not about you,” Allen adds. “It’s about what you’re trying to do. That is the great gift of photography.”

She’s had a long-standing interest in cultural anthropology, too. While studying it at Dalton during some of the most awkward years of her own life, “I was totally fascinated and kind of relieved to learn about other cultures and ways of forming families,” she says.

“I always questioned whether the way we were living was the only way to go, and whether the adults really were right in their rules,” Allen adds. “I was asking myself questions all the time.”

As her long-running gender series has unfolded, it’s only prompted more questions. In fact, “it’s people living the most important questions,” she says. “What does it mean to be a man or woman? And who makes up the rules, and why?”

In 1952, when Allen was just entering her teens, Christine Jorgensen became the first American to publicly announce her transition from male to female. “EX-GI BECOMES BLONDE BEAUTY” a New York Daily News headline shouted from the front page.

It was the first time many Americans had heard about a trans person, and Jorgensen quickly became famous—the subject of news stories and photo shoots, then the author of an autobiography, and eventually the focus of a 1970 movie, The Christine Jorgensen Story. (Actual text from its poster: “Did the surgeon’s knife make me a woman or a freak?”)

Exactly 50 years after Jorgensen first came out to the country as transgender, Kiwi Grady was an undergraduate student at NYU who had recently come out as trans herself. It was 2002: three years since the first Transgender Day of Remembrance was established to honor victims of anti-transgender violence; a year before a National Center for Transgender Equality existed.

Grady was majoring in gender and sexuality studies at NYU, but much of her education happened outside the classroom. She was a frequent face at trans demonstrations and conferences, and had founded the city’s first trans-focused college student club, T-Party.

It was only a matter of time before she crossed paths with Mariette Pathy Allen.

Allen was focusing her work on all sides of the trans community by then. Since the early 1980s, she’d been traveling the country to snap photos and give slide presentations at transgender conferences and related events. She’d photographed the cover for Read My Lips: Sexual Subversion and the End of Gender (1997)—a book by Riki Anne Wilchins that was “incredibly ground-breaking, and is still used in a lot of classes,” Cross says.

Allen often did TV and radio interviews, and her work had even appeared on film at the Sundance Film Festival. She consulted and shot still photography for Southern Comfort, a documentary about the last year of a transgender man named Robert Eads’ life, and the film won Sundance’s Grand Jury Prize for documentary in 2001.

“Mariette was positioned in a very central place because of her continued investment in the trans community,” recalls Drucker, whose college years in New York partly overlapped with Grady’s. “She was really in the center of the action.”

Allen began taking the photos that would become her second book, The Gender Frontier, a few years after Transformations came out. Those images reveal the change that was happening around her: a growing trans rights movement, a new generation who were coming out as transgender, and the diversity of people around the country—this time both men and women—who identify as trans.

“That book represented the next stage,” Allen now says of The Gender Frontier.

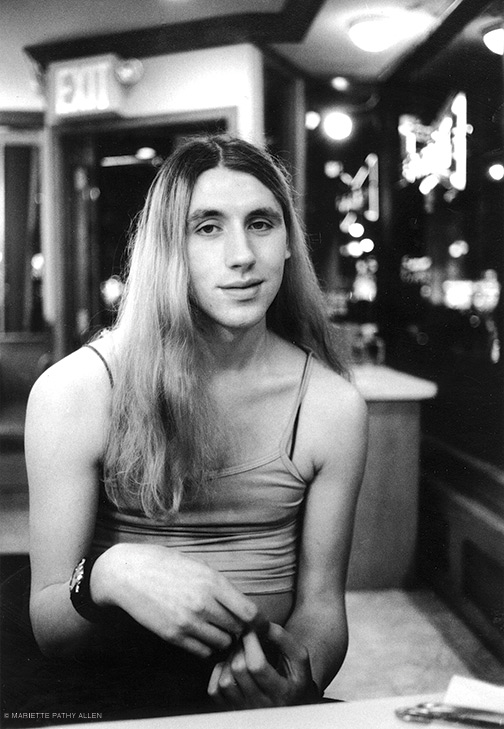

Its cover shows a 21-year-old Grady looking straight into the lens, her lips in a semi-smile. Her eyes, hair, and even arm position—along with that hint of a smile—all have a Mona Lisa quality.

The image was snapped at a time that Grady now remembers as both exhilarating and frustrating. She says that in the early 2000s, the trans community was battling sensationalized media coverage, fighting for its rights, and searching for acceptance—even among other marginalized groups. “There was still a very strong trans-phobia in certain feminist spaces,” Grady says, “and we were very angry at the larger LGB community because we felt excluded there, too.”

Along with images of protests, vigils, and lobbying trips to DC, Allen’s book again captured slices of everyday life: dance lessons, horseback rides, hospital stays, frolicking in the mud.

“It was cool just to see someone trying to respectfully represent trans people in the media,” Grady says. “There weren’t a lot of positive or diverse images out there at that moment, and I appreciate what she did.”

“At that time, the community was always being represented through the eyes of other people, and that obviously can be a critique of Mariette, too—that she’s an ally, not a community member,” Grady adds. “But I think as an ally, she did a good job of trying to show the human side of the community—the diverse lives that are present and the different ways that different trans people live.”

Antonia Gilligan, who’s pictured in The Gender Frontier working in her science lab, lounging at home, and skydiving, remembers her first time posing for Allen in the early 1990s. As a trans woman, “there’s always a fear that you’re just going to be used for exploitive purposes,” Gilligan says. “I’ve never had that feeling with Mariette. What she’s done is shed a light on the community—but it’s been a friendly light, as opposed to just taking cheap shots.”

After The Gender Frontier came out, Allen wasn’t sure about her next move.

She was still giving her slide presentations at transgender conferences, but fewer people were filling the seats. They’d stopped coming to her on-site portrait sessions, too—almost everyone had their own digital camera by then, and several years later, an iPhone. And thanks to the internet, the trans community didn’t have to rely on conferences to meet each other anymore. They could just find a message board or website.

“I didn’t know if what I could offer was still important,” Allen remembers. “The conferences were ending and I was feeling less and less useful.”

So she went to Cuba.

More specifically, she went to a professional conference for sexologists in Havana. It was mostly in Spanish and mostly academic, but while she was in the city, she also met three transgender women who became the focus of her next book, TransCuba (2014).

“I went wherever they took me,” she says. “I went to visit their homes and families and friends and went to events. I had a wonderful time with them and they were so open.”

In Cuba, Allen found a very different situation from the one she’d been tracking in the US. By 2012, America had its first openly transgender judge, its first openly transgender NCAA athlete, and a ruling that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act also protected transgender employees. Soon it would have trans characters sensitively represented on-screen in the hit series Transparent and Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, “the situation for them was so terrible,” Allen says of the transgender women she met there. “There was still so far to go.”

She discovered that transgender people in Cuba couldn’t legally change their names and had limited job opportunities. Most of the trans women she met worked as prostitutes and had become HIV positive. “The other problem was the bullying,” she says. “If they went to school, they would be bullied not just by the other students, but by the teachers as well. So they dropped out.”

But Allen also observed a country on the cusp of change. Decades after Fidel Castro had sequestered gay men in military “re-education” camps, his niece Mariela Castro was running the Cuban National Center for Sex Education (Cenesex), championing LGBT rights and acceptance.

Cenesex exhibited a selection of Allen’s work in 2014 and again in 2017.

Keren Moscovitch, an artist who teaches at the School of Visual Arts and curated the Cuba show, says Allen’s work is both “a poetic form of storytelling” and a type of political activism.

And whether it’s her Cuba pictures or her earlier work in the US, “I’ve just been particularly drawn to the intimate nature of her work and to the engagement and emotional involvement that she has with the people in her photographs,” Moscovitch adds. “She’s not a fly on the wall. She is a participant, a friend and a partner.”

“I’ve seen her photograph a few times,” notes Drucker, the artist and Transparent producer, “and I think she has an incredible ability to reach people and to see people.”

Drucker considers Allen “the single most dedicated photographer of the trans community.” While well-known artists including Nan Goldin and Diane Arbus have “glimpsed into our lives,” Drucker says, “Mariette is the only one who has embedded herself and invested her time and creative labor into investigating trans and gender non-conforming lives.”

“She’s our photographer,” Drucker adds.

Allen had a good feeling about 2018.

Her fourth book, Transcendents: Spirit Mediums in Burma and Thailand, came out in late 2017, raising fresh questions about gender expression and acceptance. (In the places Allen visited—two countries known to be homophobic and transphobic—she found that genderfluid spirit mediums were not only accepted, but revered.)

The new book sparked a fresh crop of articles about Allen and reviews of her work. Then a collection of her photos appeared in Aperture, a major photography publication, at the end of 2017.

She was eager to see what would happen next as the calendar rolled over to 2018. She hoped for an exhibition or maybe some book signings. Anything that would indicate an uptick of interest around her work.

“I thought, This is going to go somewhere,” she says, back inside her apartment, the end of 2018 then only a few months away. “And, well, it hasn’t so far.”

Her work is in a number of museum collections—the Corcoran Gallery of Art in DC, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and Portland Art Museum, among others—and private collections, too, but she doesn’t currently have a gallery representing her and she’s had limited exhibitions of her work over the years.

Does she feel under-recognized? “Yes, to be honest with you,” she says with a small laugh.

Even Erin Cross, who calls herself “a professional queer,” hadn’t heard of Allen before.

“I was shocked that I didn’t know who the heck she was,” Cross adds. “She’s done this groundbreaking work. What is it that has kept it to the side, not just in the mass appeal sense, but even in niche communities?”

Drucker says it’s because trans stories in general are still only a small piece of public discourse. “For me, Mariette’s big,” Drucker says. “But in the larger world, the trans zeitgeist is so peripheral still. I’m constantly surprised at how little people know.”

Granted, there are institutions that have taken notice. Duke University’s Archive of Documentary Arts has been preserving Allen’s work since 2006. Today the Mariette Pathy Allen Photographs and Papers includes over 900 items.

Laura Micham, who directs Duke’s Center for Women’s History and curates its gender and sexuality history collections, says Allen’s work is “a significant contribution” in the school’s commitment to documenting transgender communities.

Still, 2018 didn’t turn out the way Allen had hoped. So she sits in her chair, eyes fixed on the wall of windows across from her, looking out at New York City and wondering what its art world might want from her. Should she shift her focus to mixed-media and one-of-a-kind pieces? Or maybe it’s time for a retrospective book.

“I am struggling,” she later admits, to figure out her next steps.

The transgender community, once pleased that Allen wanted to document their lives and struggles, is no longer as interested in posing for her. “The focus now is that transgender people should photograph transgender people, and why do you need an outsider?” she says. “I began at a time when I really was needed, in many ways. Now I am not.”

Allen is still in touch with many of the people she’s shot over the years, but now they swap stories about grandkids rather than connecting over intimate portrait sessions.

As she flips through old pictures in her apartment, remembering the most prolific years of her gender series, it’s hard not to wonder if her long-standing interest in marginalized people—the invisible pull that drew her toward the group at Mardi Gras, that bonded her with Vicky West and the hundreds of people she’s photographed since—stems from her own feelings of isolation as a kid.

She bristles at the suggestion. “It’s too personal, and also a put-down of my work,” she says. “It suggests that I wouldn’t have done this unless I myself had had struggles.”

But maybe there’s another way to see it. Maybe a difficult childhood left her with more compassion and empathy than most. Maybe it gave her special powers to see people for who they are.

“Yeah,” she says thoughtfully, eyes drifting back over to the window. “I guess that’s a good way of looking at it.”

Molly Petrilla C’06 writes frequently for the Gazette.

I missed this article when it originally was published. But, I saw all of the reactions in Letters to the Editor in the current issue of The Gazette. And, as I suspected, I have to ask, “why all the “hoopla”? People canceling their subscriptions, demanding to never hear from Penn again, criticizing the Editor for “extreme liberal political agenda.” Wow! I thought of all places, my community of Penn alumni would be a respite from the insanity of hate, bigotry and closed-mindedness that is America today! Educating, validating and celebrating human differences is not a political agenda, it’s a human agenda. How is it that so many are not “woke” to being authentically human? To those who want nothing to do with an institution that continues to challenge us with what makes us uncomfortable, less ignorant and more empathetic, I am sad for you. Sad because you obviously never bought in to the values of a Penn education, and sad because you are an outlier – certainly not representative of the majority of our alumni. I wish you would stay, but if you must go, at least do so with the acknowledgment that you see “the splinter” in Penn’s eye, but not the “beam” in your own.