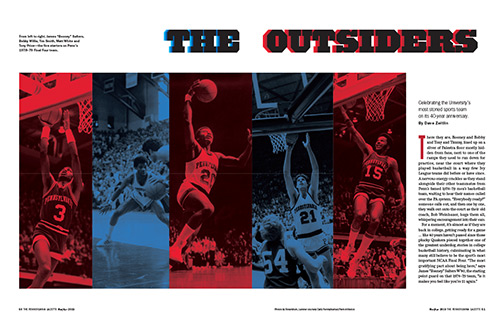

Celebrating the University’s most storied sports team on its 40-year anniversary.

BY DAVE ZEITLIN

There they are, Booney and Bobby and Tony and Timmy, lined up on a sliver of Palestra floor mostly hidden from fans, next to one of the ramps they used to run down for practice, near the court where they played basketball in a way few Ivy League teams did before or have since. A nervous energy crackles as they stand alongside their other teammates from Penn’s famed 1978–79 men’s basketball team, waiting to hear their names called over the PA system. “Everybody ready?” someone calls out, and then one by one, they walk out onto the court as their old coach, Bob Weinhauer, hugs them all, whispering encouragement into their ears.

For a moment, it’s almost as if they are back in college, getting ready for a game … like 40 years haven’t passed since those plucky Quakers pieced together one of the greatest underdog stories in college basketball history, culminating in what many still believe to be the sport’s most important NCAA Final Four. “The most gratifying part about being here,” says James “Booney” Salters W’80, the starting point guard on that 1978–79 team, “is it makes you feel like you’re 21 again.”

A couple of hours before Penn’s Final Four team was honored during halftime of the Penn–Princeton game on January 12, Salters walks around the Palestra concourse, catching a glimpse of his 21-year-old self—smiling, a net hanging around his neck—in a picture on the wall. “Were you a player on the team?” a fan asks him as Salters arrives at the door to the Class of 1978 & Class of 1979 Atrium, which served as home base for most of the 40-year anniversary festivities. “James ‘Booney’ Salters,” he replies with a knowing smile, making sure to include the nickname that was so ingrained in college that it was on his license plate. The man eagerly asks for his autograph.

“That’s the thing I really enjoy the most—seeing how much joy we brought to people’s lives,” says Salters’ partner in the backcourt, Bobby Willis W’79, sitting up in the Palestra stands and watching pregame warmups. Back in the Atrium—which connects the Palestra to the basketball practice facilities and was adorned last year with giant photos and murals of the 1977–78 and 1978–79 teams—the joy is easy to see. One former season-ticket holder, Sally Katz C’82, wears her old “Show No Pity in Salt Lake City” T-shirt, which was the hot commodity on campus leading up to the 1979 Final Four, held in Utah’s capital. She’s chatting with Robert Oringer W’82, who came up with that slogan and designed those shirts as a freshman. “It just rhymed,” says Oringer, who flew in from Montreal for the 40-year anniversary party. “It wasn’t like an advanced Wharton marketing class.”

Forty years ago, the Quakers liked to say they had a secret. The slogan began when, while warming up for their second-round NCAA Tournament game versus North Carolina, then-assistant coach Bob Staak, sensing a bit of apprehension, told the players, “We’ve got a secret. Nobody knows it but we’re gonna beat these guys.” And then Penn did just that, pulling off arguably the best win in program history. After two more victories to get to the Final Four, the Quakers’ new motto became “It’s no longer a secret.” A banner with those words once fluttered across Walnut Street.

While it hasn’t been a secret in the 40 years since, the accomplishment, in many ways, has become even more impressive over time as no Ivy League basketball team has come nearly as close to winning a national championship. “As the years go by—and they’ve gone by kind of quickly—it seems to become more and more precious,” says Tony Price W’79, the star of the 1978–79 squad.

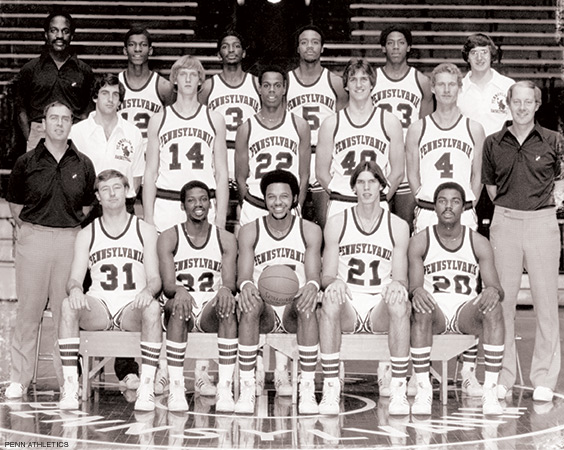

As such, the University has made a concerted effort to embrace its illustrious basketball history, first honoring the 1977–78 Sweet 16 team (which featured the core of the Final Four squad) last season during the dedication of the Atrium. And this year’s festivities, which included giving out rings and presenting Weinhauer with a framed jersey, marked Penn’s first official celebration of the Final Four team since its 25-year anniversary. “I can’t believe they’ve done so much for us in putting together this day,” says Tim Smith C’79. “It really warms my heart to know they care that much about our team.”

Smith, the second-leading scorer on the ’78–’79 squad, admits he doesn’t get back to the Palestra as much as he’d like anymore. But he knows he’ll always share a special bond with Price, Willis, and Salters. Tragically, the fifth member of the team’s starting lineup, center Matt White C’79, was killed in 2013 by his wife Maria Garcia-Pellon, who was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter (but mentally ill) in his stabbing death in their Delaware County home. White had reportedly taken her to a hospital to address her delusional behavior one day before the attack, but she was discharged with a follow-up psychiatric appointment. “If he had passed away from natural causes, that would have been one thing,” says Weinhauer, adding that most of the team attended the funeral. “This was a very, very difficult situation—one that nobody could quite understand.”

White’s two children represented him at this year’s Palestra reunion. Price stood next to them the whole time. “Matt was a big guy, very physical, but off the court the nicest person you ever wanted to meet,” Price says. “He was the greatest person—and a very big part of our team.”

The Makings of Greatness

There are a lot of places you can start the story of Penn’s magical Final Four season. A South Bronx apartment on Webster Avenue is as good as any, in a room with a few shopping bags stuffed to the top with letters. That’s where Price kept all of his college offers—and there were a lot of them.

A two-time New York City champion out of Taft High School, Price could have gone just about anywhere. Penn wasn’t even on his radar until his high school coach, Don Adams, suggested he think about going to an Ivy League school. “I thought he meant schools with ivy growing on them,” laughs Price. But after seeing the look on people’s faces when he started telling them he was considering Wharton, he knew it was the right move. “Tony was a big thing,” says Weinhauer, an assistant coach under Chuck Daly when Price arrived at Penn.

Willis, another New York City native, had known Price since they were both 12 years old. But he was ready to break free of the East Coast and had committed to play at the University of Southern California. It wasn’t until spending the summer before college in Europe that he decided he might want to stay closer to home the next four years. When Weinhauer heard the news, he jumped in a car to convince him to follow Price to Penn. “It was one of the best things that happened to Bobby,” Weinhauer says, “and certainly one of the best things that happened to our basketball program.”

For the Quakers to nab not one but two New York City public league stars in the same class was quite a score, and a testament to Daly’s formidable recruiting skills. For them to also add a Philadelphia public league standout made the group even more dynamic. Enter Smith, who met Daly after playing in the Philly high school championship—which the Penn coach called on the radio. “Have you ever thought about Penn?” Smith remembers Daly asking him. He hadn’t, even though he lived only a few blocks away in West Philadelphia. “I probably would have signed with Villanova, but I was still figuring out where I wanted to go,” Smith recalls. Two days later, he committed to Penn. “Best decision I ever made,” he says.

The first time the three African American city boys laid their eyes on the tall, lanky white walk-on from a Connecticut prep school, they weren’t sure what to expect. “Matt White happened to walk on the floor one day,” Smith says. “He was pretty raw, but his size and his willingness to learn the game was really a blessing.” Adds Willis: “When he walked in the gym, he was as strong as an ox. He didn’t have a lot of skills but we told Coach, ‘Put him on the team and we’ll teach him.’”

White would go on to an exceptional career at Penn, shooting a staggering 63.3 percent from the floor during the Final Four season (in which he was named first team All-Ivy along with Price) and finishing his career as a 59.1 percent shooter, which remains a program record. And he meshed well with his classmates from the start, joining Price, Willis, Smith, and Ed Kuhl W’79 to tear opponents to shreds on a freshman team that went 17–1. (At that point, freshmen couldn’t play on varsity—a policy that coincidentally changed for the 1978–79 season.) “I remember playing against Columbia as a freshman and we had more fans for our freshman game than they did for the varsity game,” says Smith, crediting much of Penn’s upcoming NCAA Tournament success to that season.

Salters arrived the next year to complete the Final Four core. Like the other New Yorkers, he didn’t know anything about Penn while growing up on Long Island. “I had never even heard the word college,” says Salters, whose parents grew up in the South and “could barely read or write.” His parents, though, always stressed schoolwork and his high school coach, seeing how good his grades were, suggested Wharton, even though “people in my community had issues with that because Bobby Willis was there, a year ahead of me, technically playing the same position.”

In the end, Weinhauer told Salters, “There’s no rule that I can’t have two point guards.” And so, while Price and Smith became the team’s top two offensive weapons as forwards, and White gobbled up rebounds and scored easy buckets as the center, Salters and Willis ended up forming a steady backcourt. The explosive Willis had a knack for getting to the rim while the diminutive Salters, who Weinhauer called “the smartest point guard in the city at the time,” could hit the corner jump shot and be the team’s on-court general. “The most important part about that class in front of me is they took my leadership as a junior as not a problem,” Salters says. “They looked for me to do that.”

The year before Salters joined varsity, the 1976–77 Quakers had a disappointing season, at least by the lofty standards of 1970s Penn basketball. They finished in second place in the Ivies, missing the NCAA Tournament for the second straight year and leading Price to wonder if he had made the right choice. “I started doubting things I had been doing all my life,” Price told the Gazette in a feature in the magazine’s April 1979 issue. “I didn’t know who to talk to about it. I didn’t know where to go.”

The 1977–78 season brought a sudden change: Daly quit just three weeks ahead of the first game to take a job with the Philadelphia 76ers. Weinhauer, then only 37, took over. And Price and the Quakers suddenly got their swagger back, reclaiming the Ivy League championship, and finishing No. 20 in the final AP poll. “Coach Weinhauer prepared us mentally and physically to play every game,” Smith says. “We used to call him Sarge. He was really a disciplinarian. He made sure we went to bed on time. With Daly, those things weren’t as important.”

Some say that 1977-78 team—led by a trio of seniors in Keven McDonald C’78 (whose career scoring average trailed only Ernie Beck W’53), Stan Greene C’78, and Tom Crowley W’78—was more talented than the one that followed it. But after opening the 1978 NCAA Tournament by beating St. Bonaventure in a de facto home game at the Palestra, the Quakers blew a second-half lead in a Sweet 16 loss to Duke, ending a wildly successful season in devastating fashion.

Price left the court that day with a message to himself. “I just said, ‘The next time I get in the tournament, they’re going to have to carry me off the court. I’m not leaving.’” Indeed, Price and his teammates ended up playing the maximum possible number of games in the 1979 NCAA Tournament—four to qualify for the Final Four and then two more once they got there, including a third-place consolation game (which no longer exists). “Maybe I should have been a little clearer to myself and said, ‘I need to win a championship,’” adds Price with a laugh. “I said, ‘I’m going to play the most games I can possibly play,’ and that’s what I did. I wasn’t going home early.”

The Secret

Although there were some question marks heading into the 1978–79 campaign following the graduation of McDonald, the Quakers quickly answered a lot of them in the season opener with an 80–78 win over a Virginia team they had lost to the previous year. Even better, freshman Vincent Ross CGS’92 punctuated the victory with a thunderous blocked shot, quickly showing how much Penn would benefit by the new rule allowing freshmen to play. Along with fellow frosh Angelo Reynolds C’82 and Tom Leifsen WEv’82, Ross would play a big role off the bench that year. So would sophomore Ken Hall W’81, who in his first season on varsity proved to be a valuable third guard behind Salters and Willis. “Vince Ross used to call me ‘Billy Basic’ because I wouldn’t do anything that was too far out of line,” Hall says. Weinhauer gave him a little more credit than that, calling Hall “probably the most mentally strong individual I’ve ever been around.”

Less than a month after their win over Virginia, the Quakers beat another ACC team, cruising to an 88–66 victory over Wake Forest (behind 12 points from Reynolds in his first collegiate game) to improve to 5–0 on the season. Some figured Penn should be ranked at that point, but those thoughts went out the window when the Quakers traveled to San Diego for a tournament and lost a pair of games, first to Iowa in double overtime and then to a San Diego State team led by future Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn. Some of the players enjoyed a few team bonding experiences while there—taking a bus trip to Tijuana, skateboarding on Mission Beach boardwalk, crashing a house party for New Year’s Eve—but maybe it was too much bonding. “That was a hard flight back,” says reserve forward Ted Flick C’81. “That’s when I started to not like flying.”

The losses in California proved to be a blip. Penn began the 1979 calendar year by easily winning its first two Ivy League games at Harvard and Dartmouth, before enjoying an epic week with Big 5 victories over nationally ranked Temple and Saint Joseph’s sandwiched around a one-point overtime victory at arch-rival Princeton. That set the stage for the most memorable game of the regular season: a showdown with No. 10 Georgetown at the Palestra, televised nationally on NBC with famed broadcasters Marv Albert and Bucky Waters on the call. “There was virtually no college basketball on TV then,” says former Philadelphia Daily News sports columnist Rich Hofmann W’80, then a sports editor at the Daily Pennsylvanian. “If you got Marv and Bucky to come to your game it was a big deal.” According to those listening, Albert repeatedly said, “I don’t know if you can hear me over this crowd”—which Dan Markind W’80 L’83, then the UTV sports director, said was the loudest he’s ever heard it in “50 years of watching basketball at the Palestra.”

The Quakers lost the game by two but still made a big statement. Afterward, Weinhauer famously told a reporter, “If they’re ranked 10, then we’re 10A”—which would prove to be a prescient observation. And Penn went on to win 10 of its last 12 regular-season games, only losing to Villanova and, surprisingly, at Columbia after the Quakers had already clinched the Ivy League title with three games to spare. Weinhauer remembers the Columbia fans, in their glee, shouting, “First-round losers” at the Quakers, in reference to Penn bowing out of the upcoming NCAA Tournament in the opening round. Price, in his home city, says he didn’t hear it and wouldn’t have cared if he had. “We were getting ready for the tournament,” he says. “We weren’t even thinking about Columbia.”

Indeed, for some teams before them, finishing the Ivy League with a perfect record might have been a primary goal. These Quakers, though, took especial joy playing—and beating—top teams outside the Ivies. “The hard part was trying to stay in shape, stay at that level during the Ivy League season,” Willis says. “We were always more focused playing against the Virginias, the Dukes, stuff like that.” Adds Smith: “We all played in public league schools, and we saw more action in public league games than we did in college. We weren’t afraid of playing in hostile arenas.”

And so when the NCAA Tournament bracket came out and the Quakers learned they were a No. 9 seed with a potential second-round game looming versus tourney favorite North Carolina—in the state of North Carolina, where the Tar Heels had never lost in the tournament—most people figured “maybe they’d win a game but then they’d get Carolina and that would be it,” Hofmann says. The players, though, weren’t scared. “I don’t think [other teams] respected our athletic ability,” Price says. “We would come out on the court, and they were like, ‘I thought we were playing an Ivy League school.’ Then they’d see us start playing and realize they were going to have a rough night.”

Iona, coached by Jim Valvano, learned the hard way as the Quakers beat the No. 8 seed in the East, 73–69, in an opening-round game at Reynolds Coliseum in Raleigh, North Carolina. Showing off the team’s depth, Leifsen, a 42 percent free throw shooter, made clutch foul shots down the stretch to seal the win and exasperate Valvano (who four years later would lead North Carolina State to a national championship in another one of college basketball’s great Cinderella stories). “I had known Jimmy forever,” Weinhauer says of the coach who died in 1993 after a famous fight with cancer. “So we just couldn’t lose that game. And Iona is a New York school and I’ve got three New York kids on my team. They weren’t going to lose to a New York team.”

Up next, two days later, were the mighty Tar Heels. For fans of top-seeded North Carolina, it probably seemed like a small speed bump en route to a showdown with second-seeded Duke, its biggest rival, down the road. But former UNC head coach Dean Smith expressed caution, telling reporters that Weinhauer had been an invited guest to a North Carolina preseason practice and might know a thing or two about his team. And after Weinhauer pointed to Penn’s narrow 1978 loss to a Duke team that went on to the national finals as proof that his Quakers could play with these guys, and Staak shared his “secret” with the team, Penn stunned the crowd at Reynolds Coliseum (the same place where Penn’s 1970–71 near-perfect season ended [“Almost Perfect,” Mar|Apr 2011], in crushing fashion to Villanova) with a 72–71 victory.

The win was essentially sealed when, with Penn clinging to a late one-point lead, Price pulled down a rebound and threw a long outlet pass to Salters, who hit a layup while being fouled—hard. “Tony comes running down there and they had to hold him back,” says Salters, who composed himself enough to make the ensuing free throw to put the Quakers up four. That proved to be enough of a cushion for Penn to hang on, and for Price, who battled foul trouble throughout the game, to bask in the glow of sweet vindication.

“This has to be one of the greatest feelings I ever experienced in my life,” Price told the New York Times after the game. “And we come from the so-called weak Ivy League.” The Times game recap ended with a Weinhauer quote: “We absolutely fear no one.”

Campus Buzzing

As the team’s student manager, Peter Bagatta W’79, was always looking around, observing things. That’s what he was doing after St. John’s completed what’s still known in North Carolina as “Black Sunday” by following Penn’s upset of the Tar Heels with an equally massive upset of Duke. First, he saw Weinhauer and St. John’s former coach Lou Carnesecca meet under a stairwell in Reynolds Coliseum and give each other a big hug. Then, from his seat on the bus, he watched UNC and Duke fans exit the arena in shock.

“It was like the night of the living dead,” Bagatta recalls. “Coach Weinhauer says, ‘Let’s just be quiet until we get out of the parking lot and then you can do whatever you want.’ Once we got on the road, we were yelling and screaming and hooting and hollering.”

Meanwhile, Markind and friends were enjoying their long trek back to Philly. “Every time we passed another Penn car on I-95, we rolled down the windows, yelled at them—and they at us—and blasted our horns,” says Markind, who had rushed the court from the upper deck and stormed the Penn locker room, where Staak “had brought out the cigars.” Hofmann, who also drove back to Philly that night with Daily Pennsylvanian basketball beat writers John Eisenberg C’79 and Jonathan Lansner W’79 (both current journalists), remembers “standing outside afterward and everyone is trying to give tickets away for the next weekend in Greensboro.”

Perhaps some Penn fans scooped up those tickets for the Sweet 16 and Elite Eight games, although Greensboro Memorial Coliseum was certainly far less full than it would have been had UNC and Duke advanced to the next round in their home state. The Quakers still put on a show for those that were there, surprising Syracuse head coach Jim Boeheim by running with a high-octane Orange team led by “The Louie and Bouie Show”—Louis Orr and Roosevelt Bouie. “Bobby and I had something to prove going into the Syracuse game,” Salters says. “We were an Ivy League school and people kept saying we’re not good enough to do what we were doing.”

Fueled by Price, who Boeheim called “the best forward we’ve seen all year,” the Quakers built an early 17-point lead before holding on for an 84–76 win. After the game, Smith, who finished with 18 points (second on the team to Price’s 20) rang a familiar bell, telling reporters, “I thought Syracuse was going through the motions in the first half.” Forty years later, the chip is still on his shoulder. “They took us lightly,” remarks Smith, who Weinhauer says was the type of guy who “could not be stopped when the game was on the line.” The former Penn coach adds, “I think we surprised them by coming out running the way we did. They were known to be a running team, but we were quick. We were New York City quick.”

The next game against St. John’s, the region’s No. 10 seed in the midst of an unlikely run of its own, had a different pace. “The game was a horror show,” Hofmann recalls. “It was just a rock fight.” But the Quakers, hardened by winning close games throughout the season, survived a series of St. John’s chances in the final seconds—culminating with Ross intercepting a length-of-the-court pass—to book their ticket to Salt Lake City with a 64–62 victory. Then they celebrated the Ivy League’s first Final Four berth since Bill Bradley took Princeton there in 1965. “They have a picture of me, I think, talking to [broadcaster] Bryant Gumbel and maybe cutting down the net,” Weinhauer says. “And I honestly do not remember cutting down the net.”

The celebrations were even crazier—perhaps hazier, too—back on campus in the week leading up to Penn’s Final Four game versus Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Michigan State. Bedsheets hung from the highrises, painted with signs that read “The Secret Is Out” and “The Quakers Don’t Believe in Magic” and “Michigan State Will Pay the Price.” The incredible capper came at Franklin Field where some 10,000 students and fans completely packed one side of the double-tiered football stadium for a pep rally. “You walk in and you’re like, ‘What the heck is this?’” says Hall, who was equally amazed by all the fans who followed the team to Salt Lake City. “We’re just going to play a basketball game!” It was quite the send-off to go to the airport. “That’s something you never thought would happen at Penn,” Bagatta says. “We were like the Beatles on the bus.”

Hofmann—who says the rally is “still outrageous when you think about it”—cranked out hoops content for the DP all week, including driving directions to Salt Lake City that cheekily read along the lines of, “Go to the South Street Bridge, make one left, and drive for two days.” He spurned his own advice to take an airplane for the first time and cover the first major sporting event of a career that would be filled with them. But when he got there, his journalistic impartiality collided with a despondency felt by every Quaker loyalist. “I was sitting there at halftime looking a little sad and [the Utah sports information director] said, ‘It’s not that bad,’” Hofmann recalls. “And I just looked at him and said, ‘Not that bad? It’s 50 to fucking 17.’”

The halftime score was indeed hard to swallow, and the final wasn’t much better as the Quakers crashed out of the tourney with a 101–77 loss. Magic Johnson led the way with 29 points while Greg Kelser scored 28 for Michigan State. The Quakers, meanwhile, shot less than 30 percent from the field and coughed up 24 turnovers. All the missed layups, especially early in the game, is what still sticks in the players’ craws the most. Michigan State coach “Jud Heathcote saw Bob [Weinhauer] and I later on and said, ‘You guys executed against our zone better than anyone did all year,’” Staak says. “We just couldn’t make shots.” The Quakers played better in the consolation game against future NBA star Mark Aguirre and DePaul but again fell behind by a big first-half margin, before losing in overtime.

Penn’s former players and coaches don’t believe the missed shots were due to the nerves of playing on a big stage. Some, however, think the team could have been hurt by the very thing they were so excited about at the time: all of the Penn people who made the trip to Salt Lake City. Because of the way their hotel was laid out, with the rooms facing a central courtyard, Bagatta remembers being woken up the morning of the national semifinal game by the Penn Band practicing the fight song. And the players mixed it up with fans at the hotel throughout their stay. “If we were a little more isolated,” Smith says, “I think we would have played a lot better.”

But even if there may have been some extra challenges—including a delayed flight to Utah and needing oxygen tanks at practice to adjust to the Salt Lake City altitude—the players were glad to have such support. And although Salters, who only scored two points in the Michigan State loss, spent many years wishing his team had arrived in Utah earlier and gotten more time to practice away from the crowds, he eventually was able to put the game into proper perspective. “As I got older, I realized I would not have given up that week of being [in Philadelphia] and sharing it with the city,” Salters says. “I would not have given that up.”

Setting the Bar

As one of the players who returned to the team the next year, Hall figured the Quakers would get to enjoy an encore performance. “I was under the impression that Penn would be back in the tournament every year,” he says. “After we finished going to the Final Four, all the expectations became: What are you going to do next?” At the time, he had no idea just how remarkable the run had been, or how it would mark a glorious conclusion to Penn’s golden decade. “Whoever believes what you’re doing is going to last for five years, much less 40?”

Looking back, there were certainly reasons to believe the Quakers could have continued to be a top program nationally. They had been one win away from making the Final Four in both 1971 and 1972, and several other teams in the 1970s were absolutely loaded with talent. “The Penn program was as good as any program in the country during that 10- to 12-year period,” Weinhauer says. “And so we had a lot to live up to.”

Some of Penn’s magic continued into 1980, with Salters hitting the game-winning shot in a one-game playoff versus Princeton before leading the Quakers to a first-round NCAA Tournament upset of Washington State. (Salters holds the program record for NCAA Tournament appearances with 10, having won at least one tourney game in each of his three varsity seasons). But since then, despite remaining an Ivy League powerhouse for long stretches of the past four decades, the Quakers have won only one NCAA Tournament game—exactly 25 years ago.

Perhaps the writing was on the wall. Hofmann recalls that “the rest of the league was not happy” about how good Penn was becoming, and six years later the Ivy League created an “Academic Index” to monitor the academic qualifications of recruited athletes across all eight institutions. Meanwhile, the explosion in college tuition since 1980 has made it harder for big-time high school athletes to justify going to a league that doesn’t give athletic scholarships.

College basketball also changed a lot in the last 40 years. The Big East formed less than two months after the 1979 Final Four, becoming the go-to conference for many of the best basketball players from Northeastern hoops hotbeds. A shot clock and a three-point line were added, generating more offense and excitement. And the NCAA, which Hofmann characterized as a “real mom-and-pop organization” in the 1970s, grew to become a behemoth, with its end-of-season basketball tournament evolving into the much-hyped spectacle now known as “March Madness”—with a yearly TV value of more than one billion dollars.

The 1979 NCAA Tournament is now considered a launching pad for the madness because it had expanded to include more teams (40, from the previous season’s 32), and, for the first time, seeded teams based on their regular-season performance. (The expansion continued to 68 teams but the seeding laid the framework for the NCAA tourney bracket that even the most amateur office pool gambler has come to recognize.) The national championship game that year also pitted Magic Johnson against Larry Bird of Indiana State, two of the greatest athletes in any sport. It remains the highest-rated game in the history of college basketball—something the Quakers couldn’t have realized as they watched it unfold from the stands, exhausted from their overtime loss to DePaul that preceded it. “I enjoyed watching Magic. I enjoyed watching Bird. But I was not an enthusiastic observer at that time,” Weinhauer says.

Seeing what Bird and Magic became, though, made Penn’s Final Four exit easier to swallow over time, gradually turning into a source of pride for having shared the stage with them. “The buzz that was brought in by Larry Bird and Magic Johnson really lit up the NCAA and made it a national phenomenon,” Flick says. “We were a part of that—a Cinderella-type team that wasn’t supposed to be there.” Other Cinderella teams have followed. George Mason (2006), VCU (2011), and Loyola Chicago (2018) each made stunning Final Four runs from smaller conferences. But the 1978–79 Quakers remain one of the best underdog stories in college hoops—and, in many ways, the first. “That’s the Final Four that made the Final Four what it is today,” Bagatta says. “We weren’t the stars, but I would say we were like the best supporting actor.”

The Quakers haven’t received any Oscars for their performance, but they may soon get their due on the big screen. Two young filmmakers have been working on a documentary titled The Secret Is Out: College Basketball’s First Cinderella Story. They’re still looking for more funding to complete the project, but some footage was shown on the Palestra big screen before the Penn–Princeton game, to the delight of the old players. “I guess I don’t mind being called that now, but I thought we were one of the best teams in the country,” Price says. “I was trying to win a championship; I ain’t thinking of no Cinderella.”

However he thinks of it, Price—who beat out Magic and Bird for honors as the top scorer in the 1979 NCAA Tournament with 142 points, capped by a career-high 31-point effort versus DePaul—believes the Quakers can one day return to the Final Four. “I would never say never—because if I believed that, then how did we do it?” says Price, whose son, A. J., made the Final Four with the University of Connecticut exactly 30 years after he did—before also losing to Michigan State. Most of his former teammates and Weinhauer agree with that assessment. A few pointed to this year’s team beating the defending national champions (Villanova), among other exciting wins, as proof that maybe the Quakers aren’t as far off as some might think.

Current men’s basketball head coach Steve Donahue—who took Cornell to the Sweet 16 in 2010, the closest an Ivy League team has come since 1979—believes a Final Four return is possible too. “It may be an easier path now,” he remarks, because Ivy teams tend to have more upperclassmen than the big-conference teams whose stars bolt for the pros after one or two seasons. So does junior forward AJ Brodeur, Penn’s top scorer, who enjoys the connection the current Quakers share with the program’s past stars—including Weinhauer, who returns often to speak to the team. “It’s good to set high goals to want to become a legendary team, to become cemented in Penn’s history,” Brodeur says. “Every year, some team makes a surprise run, and I bet the whole country doesn’t see it coming—except for that one team.”

No matter what happens in the future, Penn’s 1978–79 men’s basketball squad will forever be enshrined as one of the most acclaimed teams in the University’s rich athletic history. Somehow, it was a vision that Price always had, when he decided to attend a school he knew could do as much for him as he for it, hoping to carve out the kind of legacy he didn’t believe he could have gotten anywhere else.

“I want our team to be the one people think of all the time when they mention Penn basketball,” Price told the Gazette before the 1979 NCAA Tournament began. For 40 years—and who knows how many more—his dream has come true.