Considering how much has been written and said about Benjamin Franklin this year, one might reasonably assume that the subject of education—both in the Academy and College that he founded, and the broader issue of education in his era—had been thoroughly plumbed. Until recently, it hadn’t. But an exhibition at Van Pelt-Dietrich Library—Educating the Youth of Pennsylvania: Worlds of Learning in the Age of Franklin—brings that complex subject very much to life.

“The exhibit is on the educational context of the founding of Penn in the 18th century,” explains Dr. Michael Ryan, director of the Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Penn. “So the idea was to locate Penn amid a great variety of educational experiments and opportunities that pervaded the greater Delaware Valley in the 18th century by throwing light on the singularity of Franklin’s idea—and also on what was shared in Franklin’s vision.”

The exhibition, curated by the library’s John Pollack and displayed on the sixth floor, features some rare and fascinating documents and artifacts from Franklin’s era, including:

- Franklin’s notes from meetings of the Junto in 1732, which include such debate-provoking questions as “Does the importation of servants increase or advance the wealth of our country?” and his own sardonic poem on the “musty morals taught in schools”—which, according to Pollack’s essay for the show, “appears to praise female teachers.”

- A copy of the 1749 constitution of the Academy.

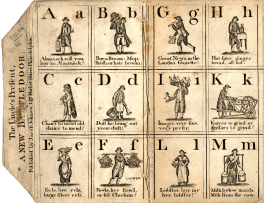

- A tiny, leather-bound book, published by Franklin in 1750, titled The Friendly Instructor, or, a companion for young ladies and young gentlemen. “It’s probably the most popular genre of literature in colonial America,” says Ryan. “Everybody’s reading these things because there are no traditions. How do you behave? If you want to be a gentleman, what do you do? What do you say in conversation? What’s proper? So this is part of the whole self-help, auto-didacticism of the society.”

- A 1769 illustration of an “electrical air thermometer” from Franklin’s Experiments and observations on electricity.

- A 1756 letter from Franklin to Peter Collinson in England, in which Franklin, after ordering electrical apparatus for the Academy, takes some shots at the Quaker “stiffrumps” in the Pennsylvania Assembly and at the rough-and-tumble politics of the man he had chosen to be the College’s first provost, William Smith.

- Detailed notes taken by a student in Smith’s physics lectures, as well as Smith’s early curriculum for the College.

“Smith is an important player for us,” says Pollack. “Plus, the science angle brings him in because he’s this committed Anglican figure, but he’s also a really interesting case study in religion and schooling, another hot-button modern topic. There’s prayer in the schools, and yet they’re also introducing the modern scientific curriculum.”

“Smith also plays a critical role in Philadelphia in the development of traditions of arts and letters,” says Ryan. “He gathered around him the best and the brightest. And nurtures them. It’s a cultural elite in a way.”

Parts of the exhibition examine the education of women, blacks, and even Native Americans in the region. While women were not accepted into the Academy or the College, “the Fourth Street campus was not an exclusively all-male bastion,” notes the program. “As many as 90 girls … attended the Charity School.”

Among the female-oriented items are Benjamin Rush’s 1787 lecture, “Thoughts Upon Female Education”; a needlework globe made by female students at Westtown School; a 1723 advertisement from the American Weekly Mercury for “Mrs. Rodes’ School” (which indicates that girls were taught basic and perhaps even advanced mathematics); and a notice in the February 10, 1757, Pennsylvania Gazette praising one Polly Hopkinson (sister of Francis Hopkinson C1757) for her “excellent performance” in the public theatricalities staged by College students.

In addition to a 1740 advertisement in The Pennsylvania Gazette for the Rev. George Whitefield’s “Negro School” and a 1776 primer by a Moravian missionary used for teaching “Christian Indians on Muskingum River,” Pollack points to a reference in an account book from the 1770s that contained a reference to an order of copy books for a “Black Abraham School.”

“We don’t know who Black Abraham was,” he says, “but that reference implies that he was running the school. Was it a black person running the school for blacks, or what? It’s very tantalizing.”

While the College in those days may seem quiet and quaint to 21st-century minds, it was in fact an “extremely urban place,” Pollack points out. “There were students in the middle of the city, with other schools and other students around them. They were involved politically. They were involved culturally. Plays were written by students taking classes here. There was poetry, orations, politics, satire. The teachers, the students—they’re going at it with each other. Teachers move from place to place—they get on the wrong side politically and so they skip out. It turns out to have been an incredibly rich place where everyone’s cooking up experiments.”

“Franklin tried to set up a place that, in the abstract, seems quite extraordinary,” says Ryan, referring to the nondenominational nature of the College’s original charter, which Smith altered in 1764 to one favoring Anglicanism. “The reality was that it was impossible. I mean, maintaining a kind of secular neutrality among the trustees was just ideologically, theologically impossible at that point in time. You couldn’t help but be ensnared by theological disputes. They cleaved every college in the Colonies.”

During the Revolution, the Pennsylvania Assembly closed the College, having concluded that its administration and trustees “stand attainted as Traitors,” and reopened it as the University of the State of Pennsylvania, with a charter more in line with Franklin’s vision. In 1789, a more conservative Assembly allowed the original College to reopen, with Smith as its provost. There were now two institutions of higher learning in Philadelphia, a situation that produced another item in the exhibition: Francis Hopkinson’s satirical Oration, which might have been delivered to the students in Anatomy, on the late rupture between the two schools in this city. Two years later, the two financially struggling institutions merged into the University of Pennsylvania.

Though the exhibition is obviously focused on the past, it does provide an interesting perspective on the state of education in the 21st century.

“I think John makes a really good point [in the exhibit catalogue], that in light of the demonstrable failure of so much of public education and the renaissance of the Ma and Pa home-schooling and charter schools, the whole thing pretty much does return us to the origins of this country,” says Ryan. “The intense preoccupation with education, because education is seen very early on as absolutely critical, is sort of hard-wired into us as a culture.”

—S.H.