In her new book, Trustee Professor of French Joan DeJean counts the many ways—from padded sofas, to “casual” clothing, to flush toilets—that France taught the world how to make itself comfortable.

By Caroline Tiger | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Joan DeJean initially wanted to call her new book The Sofa. Sitting and all its accoutrements—sofas, chairs, benches, stools—is not something the Trustee Professor of French in the Department of Romance Languages takes lightly.

Greeting me at her apartment on the top floor of a three-story townhouse on Delancey Street in Philadelphia, she offers some advice as I take a seat on her 19th-century, blue silk-upholstered sofa. “It’s only comfortable if you put a pillow behind your back,” she says, moving our conversation over to a pair of 1920s tub chairs after a few minutes. “Feel how much support this gives you?” she asks, sitting lightly in one of the chairs after briskly collecting the drinks she’d set down near the couch.

A few weeks before meeting her in Philadelphia, I spoke with DeJean by phone from her Paris apartment, where she was spending the recent winter break, and she described for me how she was seated. “I’m sitting in an armchair that’s comfortable,” she said. “Nevertheless, I’m sitting in it sideways, and I have my legs draped over one arm and propped up on the edge of my sofa.”

DeJean talks, moves, and writes quickly—she has published nine books and edited or co-edited 11 more since 1977. In other words, she’s no slouch in her field. Still, she’s an expert on lounging, having studied its origins and history for that new book, titled not The Sofa but The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual—and the Modern Home Began (Bloomsbury USA).

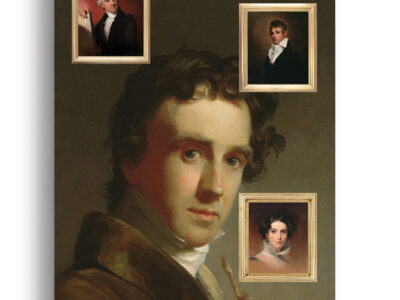

The Age of Comfort, named one of 2009’s top Art and Architecture books by The New York Times, follows DeJean’s 2005 book, The Essence of Style, which traces modern luxury back to Louis XIV [“All Things Ornamental,” Mar|Apr 2006]. After finishing that one, DeJean began taking note of various 18th-century portraits from France and England. What caught her eye was how people were sitting differently depending on the period and the place—in French portraits the subjects reclined on sofas, while the English sat upright in stiff-backed chairs. She began to wonder about these disparities. “No one would have been able to do this,” she said of her own relaxed posture in Paris, “without various new kinds of furniture.”

Style and Comfort represent both a continuation of and a departure from DeJean’s earlier scholarship on French literature, the history of women’s writing in France, and the history of sexuality. “Joan was a pioneer in the feminist readings of French texts, and in the feminist literary critical movement, a field that was neglected for many years,” says Lance Donaldson-Evans, Professor of Romance Languages and undergraduate chair of French. He and DeJean have been colleagues for 30 years.

He cites two of her works as classics in their fields: Tender Geographies (1991) argues that women were the originators of the modern novel in France; and Fictions of Sappho (1989) looks at the changing cultural context of female sexuality from the mid-16th century to the mid-20th century by examining how each age received the work of the great female poet of antiquity. “Joan has a world-renowned reputation,” Donaldson-Evans says, “because her work is original and her research is minute.”

That minute research posed significant challenges while DeJean was working on The Reinvention of Obscenity (2002). Even for an experienced, tireless researcher, tracking down censored documents that had been suppressed or destroyed was a trial. She met the challenges, but she made a resolution. “One day I just decided I will never do this again,” she recalls. “I wanted to do something different, something where you can see the results.” It’s what led her to embark on The Essence of Style.

At the same time, writing about material objects and cultural history in the 17th and 18th centuries in France was a natural extension of her research interests. The texts that she’d been poring over since she was in grad school included firsthand accounts of changing mores and practices written by people who were living through them. Francoise de Graffigny, a female novelist DeJean has studied extensively, is one of these writers whose correspondence the professor has mined for clues. When she moved from one place to the next, the writer would fall newly in love with her surroundings and describe the furniture, fabrics, and color schemes in great detail. “When something is new, you write about it,” says DeJean. “When things matter to you, you note them.”

Furniture has mattered to DeJean since her childhood in Opelousas, Louisiana, a small town deep in the heart of Cajun country. “Growing up there in the 1950s and ’60s,” she says, “was probably closer to growing up in France than it was to growing up in the United States.” In line with French custom, her family ate a large meal at midday. Her grandmother tatted her own lace, baked her own bread, and sourced all the ingredients for family meals from the garden. There was no TV and no way to know the rest of the country wasn’t living this same small-town life. (Once TV did arrive and DeJean saw what other children were eating, she begged her mother for canned food.)

DeJean’s family arrived in Louisiana from France in the early 1800s— they’ve deduced from documents that the first to emigrate was an officer in Napoleon’s army—and would go back and forth between their new and old countries, the professor says. One relative was sent to France as the ambassador of the Confederate states. When France decided not to favor the South in the American Civil War and put an embargo on everything coming from the region, his ship was stuck off the coast of southern France for most of the war. He and the other men on board passed the time by staging marksmanship contests. The journeys across the water went in both directions. Relatives in France would send young cousins with nothing else to do over to Louisiana for a spell. “There are some very touching letters written by these young people arriving in Louisiana at the mouth of the Mississippi,” says DeJean. “I imagine it must’ve been fairly terrifying leaving a slightly more advanced society in France to come here.”

DeJean’s parents and many of her relatives worked in the family business, a company that packaged and sold balms, salves, and natural remedies to drugstores all over Cajun country. Summer vacations were spent making up little packages of Epsom salts.

DeJean traces the beginnings of her appreciation for furniture back to watching her mother at her sideline business of restoring antiques. “I think the work on furniture definitely began then,” she says. An antiques dealer in town also had an influence. Mr. Leonce, a Frenchman who specialized in art glass from Lunéville in Alsace-Lorraine, took DeJean under his wing. “I had permission to go to his shop after school every day,” she says. “He would sit me up on the counter and teach me very seriously about all different kinds of French glass.”

With the advantages of such a background, a career studying French literature and cultural history would seem preordained for DeJean, but she was actually acting against her family’s wishes in her choice of profession. Her grandmother spoke French with nearly everyone except her granddaughter. “By the time I came along she had come to the conclusion—and she was not wrong—that French was over and English was the language of the future,” DeJean says. “She wanted to make sure my English was good, so she ordered everyone to speak English with me.” Her wish for her granddaughter was to get an education in English and become a doctor. “Rebellion was easy,” says DeJean. “Doing French was a rebellion.”

That would come a little later. At first, DeJean adhered to her parents’ and grandmother’s wishes, staying in Louisiana and in 1966 starting at Newcomb, the women’s college at Tulane University, as a pre-med. But pre-med didn’t last long—she was the only woman in the program and the professors weren’t eager to have her in their classes, she recalls. Shifting to languages, she studied some Russian and French and ultimately decided she wanted to go on to study with Georges May, a professor of 17th and 18th century literature at Yale, who, she says, turned out to be a great mentor.

“I went over my parents’ dead bodies,” DeJean adds. “My father didn’t think women needed an education. He was quite clear—he felt that perhaps a year or two of college were in order to be a good secretary, and if I were lucky enough I’d marry a doctor.” Instead, she earned a master’s and a doctorate in French literature at Yale and began her career as an assistant professor at Penn in 1974. In 1978, DeJean left for stints at Yale and Princeton, returning to Penn 10 years later.

The professor’s education in the history of furniture and other everyday objects continued as a young academic in Paris. To take breaks from her research at the old National Library, DeJean would pop over to Druout, a venerable auction house down the street that staged multiple sales each day. She’d skip lunch, eating a yogurt on the way, to get there in time for the auctions’ previews, which ended at one o’clock. She absorbed information from watching dealers and specialists discuss the furniture as they flipped it over and inspected it from every angle. Though she never imagined at the time that she would write about the history of furniture, this was a harbinger of the kinds of research she’d find herself doing for the book she thought of as The Sofa—a working title that immediately met with resistance, DeJean recalls.

“People kept saying, ‘No, you can’t call it that.’” They felt she needed to widen her scope. So gradually she looked into other aspects of the portraits that had first engaged her and thought about what else made it possible for people to sprawl in one country while those in the next country were sitting as if they had books balanced on their heads. “In fact, the clothing was different in France than in England—the fabric, the rooms in the home in which the furniture was positioned. All these things. I worked from the sofa up. That’s how it took shape.”

On one research trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, a curator brought out a dress from 1725. “At one point she went to check something on the computer,” says DeJean, “and I tell you I have never been so tempted in my whole life to just slip my arm in.” (She didn’t.) Another highlight was a visit to the 18th-century Chateau de Montgeoffroy in the Loire Valley, which had been in the same family since the manor house was built. Nearly everything was original, and the place was the embodiment of the architect-designed interiors DeJean writes about in a chapter of Comfort. The woodwork had been planned in concert with the furniture.

“They still have the sofas,” says DeJean. “And you see them and you see how the woodwork and the shape of the room frames them.” While at the chateau, waiting for the next public tour to begin, DeJean and a friend spied a woman walking up to a side door with grocery bags. DeJean approached her and told her she’d been working with an expert in 18th-century textiles on how to date fabric, and he’d mentioned this chateau still had some of this fabric. “I asked, ‘Would I see the fabric on the tour?’” DeJean recalls, and the woman replied it was only in the family’s private rooms. The woman ended up being the Marquise of the estate, and she offered DeJean a private tour. “When we got to her bedroom,” DeJean recalls, “she still had the 18th-century closets and doors, which are so beautiful. I was so excited.” DeJean and the Marquise now email one another, and the Frenchwoman has invited her back next summer with the promise of an even better tour.

With The Age of Comfort, DeJean has made experiences like these accessible to every reader. Taking her research and packaging it in a way that appeals to non-academics—sharing it with a world beyond graduate students and professors—is now a defining aspect of her career. The fact that her two most recent books weren’t published by university presses, she says, doesn’t make them any less scholarly. “There’s even more research involved,” she says, “because there are so many things I don’t know.”

Take the time she visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, carrying with her a Xeroxed stack of those disparate portraits of lounging French folk and upright Brits. A young curator showed her how to look at a chair or sofa’s back legs to see how it’s built to handle stress. “She had me thinking about joints,” DeJean says. “We were on the floor lying beneath 18th-century sofas, looking at stress points.”

DeJean is starting to bring her recent research to undergrads, too. This semester she’s offering a course that had previously been open to grad students only: French 350, “The Invention of Paris,” looks at the city’s evolution, from 1630 to 1730, into the intellectual, cultural, and artistic capital of Europe.

On a Wednesday in mid-January, French 350 is meeting for its second class of the semester in Van Pelt’s wood-paneled Lea Library. DeJean and 11 young women discuss an array of 18th-century broadsides laid out on the seminar table. “Literacy is not just for aristocrats who went to school,” DeJean tells the class, beginning to paint a picture of the period. “The average person who could buy things could read. I can’t tell you how amazing this is.”

She singles out an ad for a shop that contains an illustration of its sign. “The streets weren’t numbered yet,” she says. “That began in the late 18th century. So how do you find someone? You say, ‘I live at the shop sign.’ Or, ‘I live two houses down from the shop sign.’ Can you imagine the streets of the city with whole walls covered with these signs?”

DeJean has collaborated with the staff at Penn’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library to help them acquire materials from French dealers, including a number of 18th-century political pamphlets she’ll teach in this class. “These help students understand the ephemeral life of this early modern time,” says John Pollack, library specialist for public services. “These are the kinds of things people would see on the streets, that would’ve been distributed during a hot political moment.”

DeJean has also donated a number of books to Penn—29 entries in the library’s online catalog list her name as their provenance. These include a 1752 edition of Lettres d’une peruvienne, the most important novel written by Mme. de Graffigny, and a 1759 edition of Voltaire’s Candide.

DeJean’s enthusiasm for her finds and the connections she’s able to draw between them bubbles over in her vivid, animated prose as much as it does in person. In “The Flush Toilet,” chapter four of Comfort, DeJean shows the evolution of some highly intimate practices in the court of Louis XIV. Until the turn of the 18th century, she writes, “even great nobles did not mind being seen while sitting on a closestool,” a portable boxy stool with a ring cut-out and a baseline pan to catch droppings. The Sun King, we are told, received visitors and did his business while doing business—as did his grandson’s wife, the Duchess of Bourgogne, who simultaneously “chatted with the ladies of the court.” In one incident demonstrating the lack of guest facilities at court, a princess partakes of a grand meal at Versailles, then takes to the hallway and hikes up her skirts to relieve herself right then and there.

Thanks to these hard-won details, it’s easy to picture the duchess on her stool and to hear the rustling of the princess’s skirts. DeJean’s knack for rendering the historical immediate partly explains the appeal of her books. “They’re so enlightening because you not only see how we live and how it has evolved,” says her literary agent, Alice Martell, “but you also feel an intimacy with people who lived centuries ago.” DeJean’s thesis in Comfort, that France in the 1700s was a time and place during which many contemporary concepts, practices, and material objects first emerged, makes history relatable. “What we think of as contemporary is really history,” says Martell. “There’s actually this intimate connection with this period with which you thought you had nothing in common.”

From the comfort of her 1920s tub chair in Center City Philadelphia, DeJean speaks of history as if it’s highly immediate. She seems as excited as if she’d just now discovered Louis XV’s great adventures in plumbing. “I just get the giggles when I walk around Versailles and think about them ripping out those walls to put in pipes,” she says. “I mean, it was a real change in what I consider creature comforts,” she continues. “And it spread amazingly quickly, like storage. Storage was amazing. In less than a half century the trunk is superseded by a chest of drawers. It becomes affordable that fast. I mean, imagine.”

Caroline Tiger C’96 is a Philadelphia-based freelancer who often writes on design.