As rebellion rocked Egypt in early 2011, several Penn scholars had unusually intimate perspectives on the action.

By Trey Popp

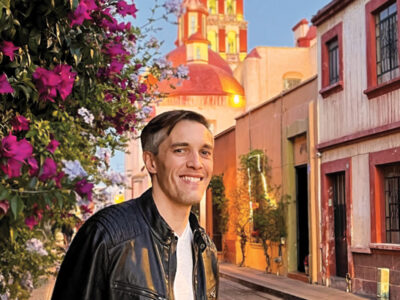

Photography by Tara Todras-Whitehill C’00 EAS’00, who covered the Egypt and Libyan uprisings for Associated Press.

Plus: Penn students react to the uprisings

On January 7, 2011, four days after arriving in Cairo to conduct a final round of field research for his dissertation, Eric Trager found himself in the home of a former Egyptian State Security Court judge. Trager, a doctoral candidate in Penn’s political science department who speaks Arabic, had interviewed scores of Egyptian political figures over the previous five years. His area of expertise was opposition politics—specifically, the ways opposition parties had been repressed or co-opted by the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Mubarak’s mastery of political suppression was reflected both in his 29-year reign and in the working title of Trager’s thesis. “My dissertation,” he recalled in February, “was on ‘durable authoritarianism.’”

The former judge wanted to talk about something else. The two men spoke in a parlor whose ambience gave their conversation a peculiar, almost surreal cast.

“His living room was bizarre, because it was just full of tchotchkes,” Trager recalls. “A ton of tchotchkes, to [the point] where there was just no room for us to sit. There was elevator music playing in the background, which was odd. I wasn’t facing him, because there was an antique couch between us. And he said, ‘I want you to take down a couple notes.’”

“‘The things that you’re seeing happen in Tunisia and Algeria are going to continue in Egypt,’” the man continued. He was referring to events that had been set in motion three weeks earlier, when a 26-year-old fruit-and-vegetable seller in Tunisia had doused his body with paint thinner and set himself on fire to protest police brutality. The act had touched off wider clashes between citizens and police. Most recently, the Tunisian Bar Association had led a general strike as conflict intensified.

But in Egypt life had gone on as usual the entire time. To Trager and other seasoned observers, the Mubarak regime seemed yet again to be in comfortable control. It was doing everything it could to make sure that nothing would change—wages, food prices, Cairo’s famously nonstop nightlife—and that the sense of continued normality would act like a narcotic on any dissent.

“‘There’s going to be a major uprising here. It’s coming,’” the former judge declared.

Trager listened and gazed at his surroundings. “I sort of heard ‘Don’t Cry for Me Argentina’ in the background, and I’m looking at all these tchotchkes, and I’m thinking, Yeah, right.”

One week later, Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali dissolved his government and fled to Saudi Arabia. In Egypt, life went on. In Algeria, where the government had quelled demonstrations and riots over hikes in food prices by suspending taxes on some staples, a wave of self-immolations swept across the country in protest of housing and employment policies. In Egypt, life went on.

Trager went about his work. Having interviewed numerous members of the Wafd, Ghad, and Tagammu parties, as well as a fair share of so-called Facebook activists, he began speaking with members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Some opposition activists with whom he spoke echoed the former judge’s prediction. Trager found it hard to share their optimism.

“They kept saying: ‘January 25 is the day that we’re going to take the street,’” he remembers. “Now, January 25 had been on their calendar for a very long time. It’s a day that honors the police for their role in 1952 protecting the people from the British. It’s a remnant of the Free Officers Revolution. In recent years, though, January 25 has been a day of protest, given police brutality. So this was going to happen anyway. It had been tried before, and quite frankly, it had failed.”

When he went downtown on the appointed day to report on the demonstration for The Atlantic’s web edition, it looked like another failure was in the works. His companion, an Egyptian lawyer, shared his assessment. At one o’clock in the afternoon he turned to Trager and said, “If nothing happens by 2 p.m., the day is done. It gets dark early in Cairo this time of year; the day is done; nothing’s going to happen.”

The next hour lasted, in a sense, for 18 days. Before it ended, Trager would get a worm’s-eye view of a revolution that truly appeared to rise from the ground up—a leaderless rebellion whose shock waves continue to reverberate across the Middle East. He would share the elation of Tahrir Square, the suffocation of tear-gas warfare, and the terror of streets commandeered by criminals and teenaged boys wielding clubs and swords.

His up-close insights, combined with those of two other exceptionally well-situated Penn scholars, provide a vivid and deeply informed vantage on a series of questions that will occupy historians for years to come. Shortly after Mubarak fell on February 11—and as uprisings continued to shake Yemen, Bahrain, and Libya—they tried to begin formulating answers to some of them. What enabled this uprising to succeed where others had failed? Was it Facebook and Twitter? Al-Jazeera? WikiLeaks? Was it the machinations of established opposition party leaders, or the enthusiasm of a generation that had little use for that establishment? In a region whose politics are seemingly dominated by hard-line religious militants, what should we make of the conspicuously secular character of the Egyptian revolution? How did previously neutered activists and ordinary Egyptians overwhelm a regime that enjoyed US support to the tune of $2 billion a year? And, perhaps most intriguingly, how many things had to go exactly right—and will have to keep going exactly right—for the pro-reform underdogs to win?

Digital Activism is Dead, Long Live Digital Activism

On April 6, 2008, another Penn doctoral candidate was in Egypt on what proved to be a seminal day. David Faris Gr’10, a student of political science known around campus for his hard-driving efforts to unionize graduate students, had befriended a group of young Egyptians who shared his soft spot for organized labor. They had launched a Web campaign and Facebook page to show solidarity for a group of striking textile workers in the Nile Delta town of El-Mahalla El-Kubra, and Faris was along for the ride.

The young men and women—eight or 10 of them, mostly around college age—had a deceptively simple goal: to persuade people to wear black or stay at home on April 6, the day of the El-Mahalla strike. They set up what Faris calls a “nerve center” at the Cilantro Internet café in Mohandessin, an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Giza, on the left bank of the Nile.

“They were fielding phone calls and updating the site and coordinating the demonstrations,” Faris recalls. “We actually moved around three or four times, from café to café, because the tech people were convinced that they were being monitored. We moved to one café and they didn’t feel safe there—they thought the owner was either hostile to them, or onto what they were doing. So we kept jumping around. It was quite tense. People were not sure what was happening. Some folks were getting news that their friends were being arrested. The people were really tense.”

Some of them piled into a white Hyundai, with Faris in the back, to go to a demonstration outside the Lawyers’ Syndicate in Cairo, a site where the regime typically tolerated protests—at least those contained by police. Police presence was heavy that day, and as more news came of arrests, the activists had a lively argument about whether Faris’s presence in the car would protect or endanger them.

As it played out, the April 6 sympathy protest was as successful as any of its organizers could have hoped—or feared. Their gambit had attracted enough support that both the regime and the international press paid a lot of attention. “One of the things that took everyone down a bit,” Faris observes, “is that they arrested one of the administrators of the Facebook group. And from there it became clear that the regime was probably going to come after them. Because they were famous, in a way.”

Faris, who wrote his dissertation about the use of digital media by Egyptian opposition activists and is now a history professor at Roosevelt University in Chicago, says that the April 6 Youth Movement’s initial success all but doomed their subsequent attempts to replicate it. The regime acted fast. “They made it harder to get Internet—they made you register with a national ID card. In Internet cafés, owners were forced to register you,” he says.

The regime didn’t try to censor the Web or ban Facebook, says Faris; it just targeted the digital dissenters. “That’s the difference between a place like Egypt and a place like Saudi Arabia,” he explains. “They didn’t try to shut down the sites; they just went after the people who were using them.”

A follow-up action on May 4, 2008 fizzled. As Eric Trager tells it, by this time Mubarak had figured out how to turn the public nature of the Web against the activists: “May 4 is Hosni Mubarak’s birthday. And they were going to protest wages and prices, or something like that. And so on May 1, Hosni Mubarak announced that they were going to raise wages. So this just totally took the momentum out of this protest. Then on May 6 he announced that he was also raising prices. So it was a one-two.”

Another attempt, on April 6, 2009, also fared poorly. In a sort of postmortem report on that failure, Faris observed that by this time, in addition to monitoring the Web more closely, the Mubarak regime had implemented a “sophisticated registration-and-tracing system” for mobile phones. “The Egyptian government successfully blocked the routes of activists’ text messages during the 2009 strike,” Faris wrote, noting that an activist had told him that his colleagues had sent “2 million bulk mails and about 50,000 SMS messages” in the successful 2008 protest. Another further complicating factor, Faris added, is that “Egyptian telecommunications companies don’t offer unlimited texting services like those available in other countries … According to one April 6th leader, the movement tried to get around this obstacle by purchasing text-messages in bulk from India at a rate of $.01 per message, but the regime successfully blocked these messages as well.”

Thus Trager’s pessimism about the prospects of digital activism in January 2011. “I think you saw this also in the Iranian protest of 2009,” he says. “The regime learned how to use Facebook. It learned how to use Twitter. It learned how to figure out who was blogging anonymously, from where, and prevent those kinds of practices. So this is why there was a lot of skepticism about Internet activism, because regimes can use Facebook, too.’”

For all the enthusiasm among American commentators about the prospects of “Facebook activism,” Faris and Trager were by no means the only ones who questioned its ability to unseat digitally savvy autocrats. In an October 2010 essay in The New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell argued that because social-networking sites are built on “weak ties” between ever looser acquaintances, they are best suited to campaigns that demand very little of the participants they solicit—sometimes no more than clicking a mouse button in an abstract show of support. The sort of activism that requires actual action, Gladwell contended—especially collective action entailing significant risk—depends on a level of “strong tie” solidarity that friending someone on Facebook simply doesn’t generate.

Marwan Kraidy, an associate professor of communication and an expert on Arab media and politics, echoes that point in his analysis of the uprisings across the Middle East.

“Technologies don’t do anything if people don’t want them to,” says Kraidy, who is from Lebanon. “It’s the people who go down and demonstrate at the risk of their life. It’s the people whose anger allows them to stand up to thugs and goons wielding batons, sometimes shooting at them with live ammunition. It’s the people who feel it’s worth it to breathe in a canister of tear gas because, ‘I believe in this,’” he says. “Technology doesn’t make you believe. Technology doesn’t make you stand up to a tank.”

That’s hard to argue. It’s possible that the original April 6, 2008 protest was so effective partly because participation was as straightforward as staying in for the day. “After all,” Faris wrote, “as strong as the Egyptian state might be, it cannot go around arresting 70,000 people, many of them wealthy and connected elites, particularly if all they’ve done is stay at home.”

Yet from where Trager sat the Saturday before the planned January 25 demonstration, something was changing—even if it would only become clear in hindsight.

“All of a sudden, these opposition movements started sending out tons of text messages to even random Egyptians. Facebook messages, YouTube videos: telling people where to go, how to behave at the protest, what they should wear, what they should not do—specifically, they should not attack the police,” he recalled in February. “It was on the Saturday night before these protests that I actually heard a number of Egyptian friends who never in a million years would do anything political—because they were elite, or because they’re scared, or because they have friends who’ve been imprisoned—say, ‘Actually, January 25, I’m going to the streets.’ That sudden change in the mood I can only trace to the sudden efforts of these opposition leaders.”

David Faris traces it back a little further to explain what gave those efforts traction this time, after the previous failures. For one thing, the regime had “completely over-rigged” the parliamentary elections in November. “There’s been this sort of dance between the regime and opponents over the years, where the opposition would be allowed to win a number of seats in the Parliament, and they’d be included in the system somehow,” Faris says. “For whatever reason, the regime decided to exclude everyone else from the system [in November]. So the number of opposition seats in the Parliament fell from almost 100 to less than 10. And we’re talking about 500 seats total. So the ruling party held something like 97 percent of seats. And people just thought, ‘This is ridiculous.’”

Another Facebook group had come onto the scene, as well. The “We are all Khaled Said” group, moderated (as it later turned out) by Google marketing executive Wael Ghonim, arose in response to the killing of a young business owner in Alexandria by police. “This group,” says Faris, “had been actually putting people on the streets all summer. They were actually running protests, some of which were quite large.”

And part of what tipped the scales back in the activists’ direction, he adds, was the fact that “between April 2009 and today, there’s simply more people on the Internet” in Egypt.

“Gladwell’s right about a lot of things,” Faris says. “He’s right that the commitment levels to these groups are low. He’s right that they emphasize weak ties. But I think he misunderstands the significance of the fact that weak ties are being used … So instead of knowing a lot about five or 10 people, you know a more moderate amount about six or seven or eight hundred people—or 400,000 people, with Khaled Said. That’s important, because we do think that our willingness to participate in collective action, particularly risky collective action, is very dependent on our perceptions of what other people will do. And seeing thousands of other people committing themselves to go out to a protest might change your own personal calculus.”

In retrospect, it seems clear that digital activists played an important supporting role in the uprising, partly because they’d adopted a parallel focus on street-level demonstrations. But at the time, at least from Trager’s perspective, it seemed even more likely that the Facebook groups would undercut each other.

“I was covering this, again, for The Atlantic,” he says, “And I was pretty sure that my article was going to say that January 25th was another tease: There were a couple movements, but they were scattered and only had, like, 50 people, and they looked clownish next to the riot police. And this was all because of deep internal divisions and ego problems within these organizations. And those are real, by the way.

“I actually told my April 6 [Facebook group] friend: By the way, this is the article I think I’m going to write. And he was like, ‘Whatever you do, do not write that article. Please do not write that article. Wait.’ And I said, fine, okay. And he said that he was going to various villages in the Nile Delta region and holding late-night meetings. And he was really just all over the place, doing this kind of organizing, picking points. And I guess, like I said, they got their act together.”

The Way to Tahrir Square

About 30 minutes after his friend had counseled waiting one more hour to see if the Police Day protest would turn into anything more than the “clownish” spectacle Trager suspected it would remain, something unexpected occurred.

“You had three little protests going on in each of these sites—the steps of the High Court, the Lawyers’ Syndicate, and then the Journalists’ Syndicate around the corner,” Trager recalls. “And these were really very contained by the riot police. Riot police had it surrounded. They were overpowering the protesters.

“But then you had a march that seemed to come from just north into the street,” he continues. “They were comprised mostly of activists who I think were affiliated with either the Ghad Party or the Wafd Party—which was interesting. The Wafd Party had not endorsed the protest, but certain members had joined, and I think specifically members who had lost in the 2010 Parliamentary election. So they were no longer co-opted. Interesting, right?”

The marchers began calling out to bystanders to join them, and by the time they reached the three confined protest areas, they had achieved a critical mass.

February 3.

“The riot police had to scramble, and what they started to do is regroup and form human chains at every point along the avenue that leads down to Tahrir Square,” Trager recounted to an audience at Philadelphia’s Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI) later. “At every stage, though, when they would erect these human chains of riot police, as the marchers approached they would let them through. From where I was standing, there was no police brutality, there was no tear gas, there was no stone-throwing, there was nothing. They would let them pass.

“So my initial reaction to this was, this is pretty incredible: The police are standing down, the regime is maybe letting the protesters have their day, letting them let off some steam so that things can return to normal on Monday.

“I was walking alongside them, taking notes—and I have to say, any political cynicism that I had at that moment vanished. It was a very remarkable sight, seeing people march for their freedom, and stand up to the regime, and even brave riot police.”

“What was most incredible about it, though,” he says, “was just how domestically focused it was. It wasn’t about hating America or hating Israel. It was focused on improving the country domestically. And I think that was actually, for me, the most inspiring thing.”

For Robert Vitalis, a Penn political science professor who spent three years in Cairo as a doctoral student in the 1980s, that was one of the most significant aspects of the uprising.

“It is amazing to see ordinary people express their political demands in large gatherings in nonviolent ways, which goes against so much our stereotypes about what opposition politics are in the authoritarian or Muslim environment,” he says. “In a world where we only imagine Al-Qaedas and other kinds of militant groups, here are these vast numbers of people—many of them young, families, young and older women—expressing their political frustrations and preferences. That hasn’t been seen in the Arab world in a long time.”

Trager’s initial euphoria over the apparent detente between the riot police and the marchers quickly evaporated, however, when a contingent of protesters continued past the square and attempted to break into the Assembly of Ministers. In short order, the scene descended into a chaos of tear-gas-infused water cannons and hand-to-hand scuffles.

Trager tried to escape through the side streets, leaving his camera with his friend, who was determined to stay. Ten minutes later his cell phone rang. His roommate had been arrested. The rest of his day provided a glimpse of how dicey the situation in Egypt’s capital was about to become.

“He was filming the police beating a woman with my camera,” Trager recalled at the FPRI talk. “A henchman behind him, who was draped in an Egyptian flag yelling anti-Mubarak slogans to blend in, suddenly took the camera—which was my camera—handed it to a police officer, and beat [my friend] on the torso area so that you couldn’t see bruises on the face … [They] threw [him] into a car with a bunch of other people, including foreign journalists; drove him to a secret prison, blindfolded, in the northern part of Cairo; held him there, told him everything they knew about his family and his family’s whereabouts … and then at 2 a.m. left him to find his way home in the desert.

“For me, it really encapsulates the moment at which a protest movement that seemed peaceful, that it seemed the regime was willing to tolerate in its narrow form, turned very ugly.”

The protesters had vowed to sleep in Tahrir Square, but when Trager returned the next morning, the area had been completely cleared. “The regime had used a lot of tear gas, which you could still smell in the air,” he recalled.

The next two days were tense. “What seemed to be developing was a war of attrition, where small pockets of protesters were fighting small pockets of riot police. But it didn’t look like anything that was going to dominate the entire city.”

Then came Angry Friday. The increasingly panicked Mubarak regime began severing Egypt’s connections to the World Wide Web early in the morning, but protesters had already gotten word out calling for a mass action after Friday prayers. The game plan was simple: when mosques let out, people would march to Tahrir Square, or the nearest public plaza.

From Trager’s vantage, it was an eerie morning.

“Cairo is a very dynamic, lively city,” he says. “But at this moment, it became like a ghost town. It became like that scene in a Western movie where there’s going to be a shootout on the street, and everyone’s sort of pulling down their shutters and closing up the saloons.

“At one o’clock the first protest emerged from a mosque. And the number of protests—the number of people who joined them, and the number of locations—was so overwhelming that it became impossible for the riot police to do anything about it. And in response, the riot police absolutely blanketed the city with tear gas, to the extent that it was simply impossible to escape flying tear gas canisters, or more moderate tear-gas guns. You could see over the entire downtown and even beyond, clouds of tear gas.”

As the day progressed, the leaderless nature of the rebellion changed the nature of the protesters’ goals.

“On the 25th, the official demands were much more moderate,” Trager observes. “The interior minister should be fired, higher wages, and new elections.” But for everyday Egyptians, who by and large didn’t have any political affiliations, those demands didn’t seem to justify braving tear gas and rubber bullets. “It’s hard for people who aren’t political to unify around anything vague. They need a symbol on which to attach all of their mass anger,” Trager says. “And Mubarak, by not giving them anything earlier, became that.”

“And it was very clear to me that they were simply not going to leave until one of two things happened: either Mubarak resigns, or there was a massacre.”

February 9.

The Revolution Will Be Televised

If digital media helped opposition activists transform a few well-contained Police Day protests into an unprecedented occupation of Tahrir Square, and the regime inflicted some harm upon itself by disenfranchising a large contingent of Parliamentarians it had previously co-opted, that still leaves a big question: Why did so many ordinary Egyptians—and Tunisians, and Algerians, and Bahrainis—suddenly decide to rise up? The younger generation, much celebrated after the fall of Ben Ali and Mubarak, had previously been written off both within and outside of the Arab world as too apathetic to change a system to which their parents had long been inured. What happened?

Marwan Kraidy, who spent late January and early February devouring Arab television and newspapers on an old Dell and a new Mac, points his finger at a culprit many mainstream commentators have been hesitant to credit.

“I believe WikiLeaks is much more important than Facebook and Twitter and blogging and all of this,” Kraidy said in February, on a day when Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi blamed growing protests in his own country on teenagers drinking Nescafe spiked with hallucinogenic drugs.

In December 2010, the Lebanese newspaper Al Akhbar published a leaked cache of documents and diplomatic cables specifically pertaining to the Arabic world. Al Akhbar is a publication that defies easy categorization. Kraidy calls it “a kind of left-wing, socialist, very independent type of newspaper that on the one hand supports Hezbollah politically, but on the other hand, advocates for gay rights.” That made it hard for anyone to dismiss the documents, which were sensational and soon became daily fodder for Al-Jazeera newscasts.

“The stuff about Tunisia was unbelievable,” Kraidy says. “It showed the extent of the corruption … how corrupt the ruling family was. Especially the family of the first lady, that they were in fact a mafia that had a finger in every single business in the country.

“But most importantly, what WikiLeaks did was to give Arabs a sense of vindication—that their beliefs about politics, about the deals some of these dictators had made with the US and with each other—beliefs that until then were not respected, because they were described as conspiracy theories—were in fact very true.

“The so-called conspiracy theories were stated as facts by cables from US diplomats sent to Washington!” Kraidy continues. “Nobody, not a single leader, tried to say that these were lies. They could not. So, the private lives of Saudi princes being broadcast like that—everybody knew what was going on in those palaces, everybody knew that there was Scotch whiskey, that there was prostitution, that there were these wild parties by people whose public personas were very pious and very conservative.”

The revelations were explosive. Without amplification, however, they might have faded into irrelevance. But the Arab media sphere has been completely transformed in the last 15 years.

Twenty years ago, Kraidy points out, “the only thing they had was the state channels. If you were in Jordan, or Egypt, or Libya, or Saudi Arabia, the newscast was the newscast. Not one among many. And you evidently didn’t believe everything you saw, but you didn’t have this multitude of sources of information to compare and contrast. And most importantly, you didn’t have the kind of news that made government regime or court news look so ridiculous.”

The beginning of the end of that monopoly, Kraidy explains, came when Iraqi tanks invaded Kuwait in 1991.

“The Saudi government waited on that piece of information for four days,” he marvels. “Four days in the 1990s was a very long time! Not only did you have Saudis who saw tanks rumbling across the border and were wondering, ‘What the heck is going on?’ but you had many of them turning to the one source of information back then that was not controlled by the government, which was CNN at hotels where Westerners stayed. And immediately you had businessmen who were politically connected who said, ‘There’s a huge margin for us here. Number one, to stay on top of the information and the news cycle—to have some say in shaping what people see and hear. But also to make some decent money.’”

The Saudi king’s brother-in-law kicked it off in 1991 with MBC, an offshore channel based in London. “In 1996, Al-Jazeera starts,” Kraidy says. “The Lebanese channels went on satellite in 1996: LBC and Future TV, which did for entertainment what Al-Jazeera did for news. And the rest is history. We now have over 500 channels, all of them in Arabic, covering the whole region, most of them on satellite, and most of them free-to-air.”

This “chaotic, messy public sphere,” Kraidy says, is built on more than soap operas and sitcom reruns. “In many ways, the Arab media sphere today is as diverse as the American media sphere is—from the extreme right to the extreme left; from the extreme secular to the extreme religious; to channels that talk about American imperialism and the nasty impact of market liberalization to channels that teach you how to diversify your stock portfolio,” he says. “But I think the most important are the ones that are hard to classify, from an American perspective. Which is the kind of channel that is critical of American foreign policy in the region, but is tackling corruption, or that is doing things that are part of what the US likes to see happen in the region. So you can’t just dismiss them as, ‘They’re anti-American.’”

This bloomed into full view in 2006, when Hezbollah kidnapped two Israeli soldiers and Israel invaded Lebanon in retaliation. For Kraidy, one of the most fascinating aspects of the conflict was the spectacle it spawned on call-in TV shows. “People would call on Lebanese channels and call the Saudi king a pig, on a live show! The boundaries between what you can say in your living room and what you can say on the public airwaves completely collapsed,” he says. “And that creates a much more difficult environment for dictatorships. Many of them are very good at manipulating information—you know, most of these guys have their own Facebook pages, and have special squads that monitor the Internet, that hang out in Internet cafes, that Tweet and do all that stuff. But they’re always playing catch-up.”

To Kraidy and others, it is self-evident that one of the critical forces that enabled secular, pro-democracy protests to achieve critical mass in Egypt was that great American bugaboo: Al-Jazeera.

“Yes, some of [the protesters] used Facebook, some of them used Twitter to organize, and most importantly there were text messages,” Kraidy says. “But it was not as important as you, who’s part of a demonstration of 200 people in some small city, watching Al-Jazeera and seeing that in fact in another city there are thousands of people. That you are not alone. Let alone if you’re sitting in your living room and saying, ‘God, my cousins went down, my brother went to join them, some of my colleagues are already on the public square, I kind of feel bad about myself here sitting in my living room.’ You see all these images on an outlet like Al-Jazeera, and you feel compelled to be part of history, as opposed to sitting on the fence or on the margins. So the old medium of television was at least as consequential as Twitter and Facebook, if not much more.”

Interestingly, Kraidy thinks Al-Jazeera’s coverage of the Middle East overall was outperformed by its sister station, Al-Jazeera English. “With Egypt, they [Al-Jazeera Arabic] went all-out. With Bahrain, they stepped back—because Bahrain is in the Gulf and the Gulf Cooperation Council, very close to Qatar, so Al-Jazeera kind of betrayed that in fact that they’re not this transparent, unbiased [entity]—that they have their agendas too, and that their agenda is very aligned with the foreign policy of Qatar. Al-Jazeera English, on the other hand, I think did a better job. Some of their reporting was magnificent … They’re one degree removed from the Qatar leadership, so in a way I think they were more independent. … With Bahrain, Al-Jazeera [Arabic] was ridiculous. They were nearly propagandizing for the regime. CNN and ABC did a good job, but they didn’t have the access and the knowledge of Al-Jazeera English.”

Robert Vitalis agrees that satellite TV played a crucial part in kindling the sparks from Tunisia into an antiauthoritarian blaze that gripped the entire region.

“Everyone’s watching Al-Jazeera now, or equivalents,” Vitalis says. “People were focused on Tunisia. There were, it turns out, contacts between Tunisian and Egyptian activists. Egyptians have been smart and thinking about this. The youth wing has been trying to imagine a different politics. It’s not like they’re just grumpy one day and get up. It turns out they’ve been studying other movements and moments, and had contact with other activists in other places. We now can see how much the spread of this across the Arab world has to be explained by the witnessing of the thing itself.”

Revolution and its Impediments

“I was dodging tear gas,” Trager recalls. “I was dodging masses just running in every which direction. It was very chaotic on the ground. It frankly looked like a war zone. So it wasn’t clear to me while I was still out on Angry Friday—and I didn’t go home until about 3:30, I mean, I was suffocating—it was not clear to me that the protesters were going to be successful … I wasn’t sure how far the violence would escalate against the protesters. I didn’t think a massacre at that particular moment was out of the question.”

With Coke rubbed over his face to ameliorate the tear gas, Trager tried to find a way back to his apartment. Burning tires blocked a bridge across the Nile. Changing course, he passed a hospital where doctors were tossing facemasks to demonstrators, but Trager couldn’t get his hands on one. At last he found a taxi driver willing to take him. The scene was chaotic.

“It was when we started approaching the Egyptian Museum area, just north of Tahrir Square, that all hell broke loose,” Trager wrote several days later in The Forward, the Jewish daily. “People started banging on the windows, begging to get in to escape the effects of the tear gas, which was so overpowering that, even with our windows closed, the driver’s eyes began itching. That was when we entered the war zone. As the taxi driver navigated delicately past swarms of people blocking our path, fearing that the crowd could turn on us with any false move, tear gas canisters started to fly directly over our heads from below the highway. One after the other, they twirled in the air like gorgeous John Elway spirals, letting off plumes of gaseous smoke that stung everything in their path as they fell among thousands of demonstrators. Meanwhile, some of the demonstrators responded in kind, chipping off pieces of the highway—a small chunk of the lane divider, a swab from the side rail—and pelting the police from above. And with predictable imprecision, the police responded with rocks of their own.

“When we arrived at my apartment,” Trager continued, “the driver let out a deep sigh and refused to take any money. But I insisted, since he’d possibly just saved my life.”

The events of the next two days placed it back in jeopardy. “There was massive looting Friday night, Saturday, and Sunday night,” Trager said in February. “Basically Mubarak, when he took the police off the streets, he sent looters to terrorize the people. They hit my neighborhood Saturday night, Sunday night … Shops were broken, destroyed. ATMs were destroyed. Things were just closed.”

Into this security vacuum stepped “neighborhood watch groups,” which, Trager notes wryly, didn’t have much in common with the yellow-vested middle-aged men that term conjures in the States. “These were vigilantes. In my own neighborhood they were 16- to 18-year-old kids with guns, swords, clubs; and 10-year-olds with broomsticks. I mean, this was my first line of defense!

“That was very chilling, seeing, like, a kid with a sword, and I’m the American,” Trager says. “It was the first time I ever really felt nervous.”

The American embassy began evacuating US citizens from Cairo. Trager, who had been unable to contact his wife or family due to the Internet and mobile-phone outages, and feared that rumored electricity cuts would be next, joined the exodus on Monday, January 31. Before he left, however, he witnessed an extraordinary turning point on Tahrir Square, when Egyptian army tanks rolled onto the scene of clashes between demonstrators and regime-sponsored counter-revolutionaries.

“I thought it was brilliant, actually, because when the military retook Tahrir Square on Saturday—well, they didn’t retake it, they took it on Saturday the 29th—they really just stood there. They just sort of stood there and smiled and … kissed babies, let people climb on their tanks and [write] graffiti [like] ‘No Mubarak,’ you know. They didn’t do anything. They didn’t do anything to stop the violent thugs that went after the people. They tried to play neutral. And I actually think that they were trying to give Mubarak time to use other means to pressure the protesters out of the square. And when that didn’t work, and when it was very clear that the protesters were sort of there to stay, and you were not going to remove them without a massacre, the army made the strategic decision to ask Mubarak to leave.”

Given the leaderless nature of the revolt, the Army may have been the only entity capable of orchestrating a minimally bloodless end game.

“What we saw while Mubarak was still around,” Trager points out, “is that all the people who tried to negotiate on behalf of the protesters with the regime very quickly realized that there was nothing they could do. Because the protesters had held their line—Mubarak’s got to go—and there was simply no intermediate step that anyone claiming to represent the opposition could agree to.”

What enabled the army to step into the savior role—at least in the two weeks between Angry Friday and Mubarak’s resignation on February 11—was the fact that it was “divided horizontally,” says political science professor Ian Lustick, an expert on Middle Eastern politics.

“There are the lieutenants and captains in the tanks, who identified with the demonstrators because they have the same frustrations and the same middle-class backgrounds—and [on the other side] the generals who own 30 percent of Egypt and run the country from the back rooms, but don’t know how many of their orders would be followed by the lieutenants and the captains in the tanks if they ordered them to fire on demonstrators.

“Since the world thinks they’re in charge, they’ve got a space of time in which they can decide Egypt’s future,” Lustick adds. “But not too much time … Right now they’re trying to see how much of their money they can keep, and how much of Egypt they can continue to rule.”

Trager came back to Philadelphia in early February, then returned to Cairo toward the end of the month. Before his first journey to post-Mubarak Egypt, he voiced deep concern over the future.

“I don’t think that you’re going to have as much unity against the military as you did against Mubarak,” he said. “And I think that that’s actually going to make it easier for the military to make sure that its interests are protected. Those interests are not democratic.”

The Egyptian Army is an economic powerhouse, with ownership stakes in everything from real estate and hotels to bottled water and high-tech firms. It controls an estimated one-third or more of Egypt’s economy, and has long been shielded from pubic scrutiny.

Says Trager: “We have to ask the question, What is the Egyptian regime? Is the Egyptian regime Hosni Mubarak? Or is the Egyptian regime actually Hosni Mubarak, but really backing the military? And if the Egyptian regime is essentially a military regime with some sort of civilian leader that just keeps things under control to protect the generals, well, that could easily reemerge.”

As of mid-February, he was worried that the Obama administration would be predisposed to support such a development.

“I frankly think that the administration is going to sit back, and it’s going to allow the army to subvert a more democratic future in Egypt,” he said. “I think it’s going to do that because it sees the army as in its interests, which is true. We have a very strong relationship with the army. I’m not saying it’s a stupid thing. But I do think that these episodes should show the shortsightedness of relying on authoritarianism or relying on dictatorships for stability.”

An interesting counterpoint to that criticism comes from David Faris, a longtime opponent of the United States’ close relationship with the Egyptian military.

“I’m a critic of US policy, but I think that [the Egyptian Army’s handling of Tahrir Square in early 2011] is an argument for engagement in some way, shape, or form,” he reflects. “Because the places where we think we have some influence—even if that influence was based on years of support for an authoritarian regime—it does seem like the US was able to exert some positive influence on the Egyptian military. In a way that we have zero leverage with Libya. So as much as I’m not in favor of sending billions of dollars of year to an authoritarian regime, at the same time you could make an argument that the engagement was important in some way, or allowed us to have leverage at a critical juncture.

“It forces me to look back at the position I held, which was really against this funding altogether. I like to think that I’m a reasonable person and I will change my mind based on evidence and events, and I have to say, I think that was important.”

But engaging exclusively with the regime was woefully shortsighted, the scholars agree.

“The American government has not invested any time or energy or resources in establishing bridges with opposition movements,” Kreidy says. “That’s a huge mistake. Because if you had built bridges with the opposition with legitimate representative or various groups in the population of Egypt, then you wouldn’t have the kinds of worries that you have now about what will happen. Because when some groups are bogeymen, you’re not going to talk to them. Well, if one day they get to power, then you’re in for surprises.”

Yet he acknowledges that this kind of bridge-building is a double-edged sword. “I say the best thing the US can do right now is just stand back. Because the moment you embrace these protesters, they’re tainted.”

The bogeymen to which Kraidy was alluding, of course, are the Muslim Brotherhood. The Brotherhood navigated the roiling waters of January and February with considerable savvy, endeavoring to downplay their own role in the uprising and pledging to limit their political ambitions going forward. The organization promised not to run a presidential candidate in the coming elections, and to contest only a minority of seats in Parliament.

Lustick suggests that the Brotherhood is not as radical or intractable as many in the West believe it to be, and that replacing the regime with a more inclusive democracy might temper the Brotherhood’s hardline positions.

“One of the things democracy does,” he says, “is to take extreme views in a society and tempt those views to become enmeshed in the give-and-take of mundane, compromising politics. And over time that kind of activity builds up interests in that community that undermine the extreme views of the original leaders.”

Lustick cites a historical precedent. “This happened with the Catholic parties in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in many countries in Europe, where they formed Christian Democratic parties that were supposed to be—from the points of view of the clerics who created them—instruments of the Church. But they eventually became expressions of bourgeois political opinion in which the Church’s influence faded and faded, because of the interests of politicians in getting elected.”

Trager, whose views of the Brotherhood have been shaped by close contact, isn’t so sanguine. “Their goal is the Islamicization of Egyptian society,” he says. “And look, the Obama administration, I’ll give them credit for this: I think it is legitimately concerned about the Muslim Brotherhood gaining too much power.”

At the FPRI meeting in February, Trager recommended that the Obama administration advocate for an amendment to Egypt’s constitution that would prevent the establishment of a state religion.

“We need to have the Muslim Brotherhood pay a price for being so cautious, for sitting out [at this early stage], and ensure that once they are no longer laying low, that they can’t impose an Islamist theocracy,” he said. “If we explained what that meant and what it was, we might have traction now, while there are real voices among these protesters calling for a civil state.”

He added that it was important to challenge Islamist ideology on its merits: “We need to make it very clear that democracy requires popular sovereignty, not the sovereignty of any theological figure, not the sovereignty of God.”

A civil state has never been easy to build under any circumstances. The Arab world is no different. The exultation of February gave way to that hard reality in March. Bahraini security forces cracked down violently on pro-democracy protests, with material aid from Saudi Arabia. Libya descended into civil war. Cairo experienced an unsettling string of church bombings and Tahrir Square was the scene of attacks against pro-reform demonstrators—abetted, according to witnesses, by army officers. Meanwhile, secular and sectarian political parties maneuvered—sometimes in concert, sometimes in tension—to shape new amendments to Egypt’s constitution and to position themselves for the planned August elections. In mid-March, Egyptian voters approved a constitutional referendum that many analysts viewed as a victory for the army, the former ruling National Democratic Party, and the Muslim Brotherhood; it set a swift election timetable that places the secular reformers, who lack an organized party infrastructure, at a disadvantage. “Five weeks after Hosni Mubarak yielded his presidency to the unified masses of Tahrir Square,” Trager reported in The Atlantic, “Egypt’s could-be revolution is a deeply divided mess.”

What happens in the coming year is almost certain to have lasting ramifications for the region and the world. Before Trager returned to Cairo, he laid out the stakes.

“Historically in the Middle East, the saying has been, and the saying of the Muslim Brotherhood has been, Islam is the answer. So what is Islam the answer to? Islam is the answer to tyranny. And actually that’s been true—unfortunately, that’s been true. In Iran, Islamists toppled the Shah. In the Palestinian Territories, Hamas [defeated] the authoritarian Palestinian Authority. There are other examples.”

But as many of those examples show, the Islamist program has often replaced one tyranny with another.

“We need to show that actually, liberalism is the answer,” Trager declared. “We need to show that liberals can win. We need to show that to a Muslim public in one of the Muslim world’s most populous countries: that it can happen, that actually liberals preaching secular, mostly liberal values can make change, can topple a regime, can produce a more productive order.

“We should be heavily invested in the success of these protests.”

SIDEBAR

Far Away, So Close:

Penn Students with Middle East Ties React to the Uprisings

“I’ve been living under the Mubarak regime my entire life,” said Marwa Ibrahim, a junior from Cairo. “In some sense, what they were fighting for in Tahrir Square was my own liberation.”

Ibrahim is one among many Penn students with ties to the Middle East who have had to watch the recent uprisings and revolutions from afar. And though there is safety in distance, there is also yearning.

When protests in Egypt broke out, Ibrahim recalled later, “My daily routine completely changed.” She began obsessively watching Al Jazeera’s Internet live stream, and reading bloggers in Cairo. She even created a Twitter account so that she could stay totally up-to-date. Flying back home was not a realistic option, but nevertheless, “I felt like I wanted to protest.”

Heba Fadel, a Fulbright scholar from Egypt, echoed the feeling: “I wanted to fly home.”

“At the beginning of the demonstrations or protests, I was against it,” she elaborated. “Because whenever there are demonstrations in Egypt, people don’t get their rights, and the police or security men begin to use violence.” When her friends in Egypt read that sentiment on Fadel’s Facebook page, she said, they doubted her patriotism—but “I hated violence.”

When she saw that the protesters stood strong even as the Mubarak regime responded with tear gas, however, Fadel’s sympathy for their cause deepened. “I found that this bad regime, this corrupt regime has to face an end. And this is the end.”

Ebraheem el-Touhamy, a Fulbright scholar from Egypt who was an Arabic teaching assistant at Penn last year, experienced the protest firsthand. He said it was a rough scene. On the fourth day of demonstrations, which some protesters called “Brutal Wednesday,” pro-Mubarak forces tried to evacuate Tahrir Square by force; according to El-Touhamy, their weapons included stones and metal scraps. Looters took advantage of the situation: at night, El-Touhamy volunteered in a community patrol team, which kept watch on homes as well as churches, mosques, museums, and landmarks.

To make things worse, the regime’s imposition of a curfew forced El-Touhamy to walk the 10 miles between his home and Tahrir Square on each day of the protests.

But he said there was a strong sense of community in Tahrir that kept him going back each day. “There were many, many shows just to amuse ourselves,” he said, even arts and crafts for the children.

Many students remarked on the spirit of cooperation between Egypt’s Muslims and Coptic Christians. El-Touhamy, Fadel, and Ibrahim posited that much of the tension between Copts and the Muslims had been kindled by the Mubarak regime to distract citizens from issues within the government. “The day the Christians went to Tahrir Square and stood with the Muslims, they showed to the whole world that they don’t have any problems with the Muslims,” Fadel said.

Because she couldn’t be in Tahrir Square to celebrate, Ibrahim tried her best to bring Tahrir Square to Penn. She organized an event called “Tahrir Square, Experience the Egyptian Revolution,” which occurred on February 26. There was falafel and foul (an Egyptian fava bean dish), a performance by the Philadelphia Arab Music Ensemble, and political discussion. “It felt like I was at home,” she said.

When Ibrahim found out about Mubarak’s resignation, she was at her work-study job at the Religious Activities Common. She and her co-workers dropped everything and watched the Al Jazeera live stream. “I was like, oh my God! This is something I’m going to tell my children, my grandchildren.”

But despite the festive mood at Penn, many students from the Middle East were envious of their friends and family, who were witnessing the historical events firsthand. Second-year graduate student Ameer Saabneh, a Palestinian from Israel, said that although he was checking for news online at every free moment, “There is a feeling of missing something.” And with protests erupting throughout the region, he felt he couldn’t “find the right people to talk with about it.” So he sought discussion at the weekly meetings of the Arabic group at Gregory College House’s Modern Language Program.

American students who had studied abroad in the Middle East were as enraptured as their international classmates by the recent tumult. “The craziest thing for me is that we were living … two blocks from Tahrir Square, “ said Penn senior Yuval Orr, who studied in Egypt last summer.

“It’s hard to live in Cairo,” Orr said, adding that Tahrir Square is not a place where foreigners typically settle, due to the area’s poverty. He recalled the doorman of his summer residence, who lived, with his family, in a lean-to built under the building’s fire escape. “When I first heard about the Egyptian protests … and [the] poverty motivating the revolution, this was the person I thought about.”

A common refrain among Middle Eastern students was their surprise at the suddenness of the uprisings. “Before Tunisia, I would not have predicted anything like this,” Ibrahim said. The same went for sophomore William Dib, a Syrian who grew up in Kuwait. “I thought the Tunisian president leaving was very odd,” said Dib. He didn’t think Mubarak would ever step down.

There was one exception: most students who had spent time in the Middle East felt that Libya was a ticking time bomb. “They were all just waiting for a little push from their neighbors,” said Dib.

As unrest escalated in some countries and seemed to settle down in others, many students were beginning to wonder about the region’s future.

Ibrahim, along with her Saudi friend Marion Abboud C’10, started a blog (ShiftingSandsofEgypt.tumblr.com) to chronicle the political developments of each day after Mubarak’s resignation. They dated their first entry “Day 0”—marking February 11, the day of Mubarak’s resignation—and asked, “What next?”

There are many theories. Ibrahim is optimistic: “The youth are not going to sit back and watch another corrupt regime born.”

But others have reservations. Fadel counters that though young people were the base of the revolution, “I’m not sure if [they] will be the base of the coming elections.”

“I’m trying to really restrain myself from celebrating,” said Dib. “They can’t really call it victory unless they really establish a good government for the future.”

—Maanvi Singh C’13