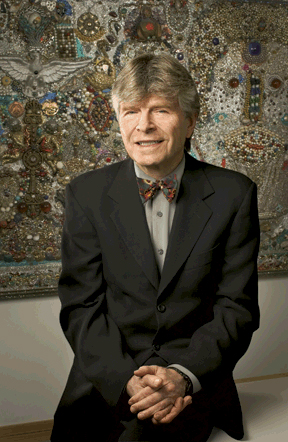

Sheldon Bonovitz W’59 is sitting in his office at the Philadelphia headquarters of Duane Morris, the law firm of which he’s chairman and CEO. Soft-spoken, trim, and elegant, with a head of thick, slightly unruly hair, he’s wearing the expected Philadelphia-lawyerly bowtie—but one that looks like it could have been painted by the abstract expressionist Franz Kline.

Bonovitz isn’t talking about the law just now. He’s reflecting on art collecting, community, and on his own mortality. “When I’m dead 25 years, nobody will know who I am or was,” he says. “Leaving your art to an institution gives you a long-term connection without being egotistical.”

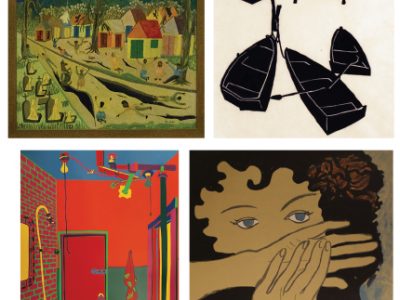

Art hangs everywhere in Bonovitz’s airy corner office high above the Center City streets, but it’s not the usual portraiture found in a venerable Philadelphia law firm. Nor is it the innocuous abstract stuff often chosen to match the chairs around a conference table. In art-world parlance, it’s Outsider Art: colorful, primitive, totemic, intensely personal—and made by untrained artists. There’s a bowling pin carved into the form of an African king wearing a robe of bottlecaps, by the Chicago artist who goes by the name Mr. Imagination; a 6-by-10-foot canvas encrusted with costume jewelry, plastic figures, and other ephemera by the West African Simon Sparrow; and a painstakingly detailed, obsessive line drawing with a devotional feel by the Mexican artist Martin Ramirez.

The art spills out of Bonovitz’s office and down the halls. There are works by William Hawkins, Elijah Pierce, Rev. Howard Finster, and the legendary Chicago bag lady Lee Godie, to name a few.

Bonovitz acquires Outsider Art for this unconventional, community-oriented law firm, as well as for himself. He speaks of these primitives with reverence: “They were janitors, waiters, people who collected trash—they all had these very humble origins. A lot of them are African American. And are geniuses. And are creating art that, at the highest level, is every bit as respected and as important an event as major contemporary art.”

Bonovitz’s own origins are also rather humble. Born into a family of wholesale fish merchants in Cleveland, he was raised in an environment “totally devoid of art.” He grew up working paper routes, selling orange drinks at baseball games, making deliveries for a butcher shop, and then working in the family fish business. “There were three white people and 40 or 50 African Americans, and that probably had an impact on what I’ve done,” he recalls. “They were friends, I went out with them. Some were amazingly intelligent—and amazingly disadvantaged. And I knew that if they’d had the opportunities that others had they’d be doing different things than what they were doing.” That realization, he adds, “has deeply affected my attitude about my own place in life and how you treat others.”

Bonovitz describes high school as a time when he read not a single book, left school at noon to go to the racetrack, and played cards every night. “I was at the edge,” he says. “I really wanted to start a new life, and I knew that I had to make something of myself.”

Off he went to Wharton to study accounting, then to Harvard Law School, where he mastered tax law. After clerking in Washington, he returned to Philadelphia to work at Duane Morris.

The historically Quaker firm turned out to be a good fit for Bonovitz, both philosophically and professionally. “I remember going to partners meetings where the only dispute would be that the senior partners felt they were making too much money and wanted to share it among the other partners,” he recalls. “That attitude of respect for the individual rubbed off.”

Named the firm’s chairman and CEO in 1998, he has grown it by leaps and bounds—more than doubling the staff, which now numbers over 550 lawyers, and increasing annual revenue from $72 million in 1997 to nearly $300 million in 2004. As he moved up at Duane Morris, Bonovitz went from tax law into myriad aspects of business development, investment, and advising, serving on several corporation boards outside the law firm, and developing several business specialties, including multi-party mergers and acquisitions.

As his law career started to take off, he met and married Jill Fleisher, the daughter of Philadelphia art dealer Janet Fleisher CW’38 and now a well-known ceramicist. Bonovitz had always had a passing interest in art, but “through Jill, I really developed much more of a passion,” he says. Influenced by Janet, a longtime champion of Outsider Art, the couple started collecting. “I love the art of the deal and acquiring art,” he says, whereas Jill doesn’t need to own it quite as much.

Since they collect as a duo, the question of differing tastes arises. “We influence each other, and I don’t think there’s one or the other of us who’s dominant,” Bonovitz muses.

Outsider Art wasn’t exactly a hot commodity when the Bonovitzes started acquiring it.

“With an unerring eye, the Bonovitzes were collecting something that wasn’t, at the time, collectible,” says Derek Dreher, director of Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum, which last year mounted a show of top pieces from Bonovitz’s cache. Dreher is particularly impressed by what he terms the couple’s “visceral passion” for the work. “It didn’t bother them that the artists were unknown. They were attracted by what they saw, and the rest of the world has come on board.” Dreher praises their desire to give back and share what they’ve created with the community.

Bonovitz currently serves on the boards of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Curtis Institute of Music, and the Philadelphia Library Company. In June, he was named to the board of the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania. He’s clearly honored by the recognition of joining the select group charged with the stewardship of one of the world’s single greatest impressionist and post-impressionist collections.

Asked to choose a favorite from the thousands of works of art he has collected, Bonovitz pauses, then mentions a stone angel in his personal collection by William Edmondson, son of former slaves, from Tennessee. “A lot of his work, especially his faces, are severe,” he says of the sepulchral-like sculptures, “but this is just a very angelic piece. It’s in our bedroom. So I go to sleep with this angel overlooking me, and I feel very good about that.”

—Amy Albert C’81