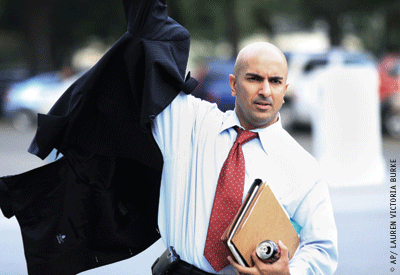

Class of ’02 | On October 3, after a 12-month span in which the Dow Jones Industrial Index shed one-third of its value and several of the country’s biggest banks and insurers suffered spectacular meltdowns, President George W. Bush signed into law a $700 billion bailout plan designed to rescue the nation’s financial system. Three days later, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson announced that the man responsible for spending that money would be Neel Kashkari WG’02, a 35-year-old former aerospace engineer who joined the Treasury Department in 2006 after several years at Goldman Sachs.

Kashkari’s new title is interim assistant secretary of the treasury for financial stability, and it represents a role that has no clear precedent in American history. Despite immediately being dubbed “the $700 billion man” and “bailout czar” by a national media that knew little about him, he downplayed the far-reaching authority of his role in a conversation with Gazette associate editor Trey Popp October 8. “Call me the chief operating officer executing Hank’s strategy,” he said.

Yet even though he is only expected to remain in the job for a few months—until the new presidential administration takes the reins—Kashkari faces a daunting task, evidenced by the fact that in his first 72 hours on the job, the stock market lost more than $2 trillion in value. He spoke with the Gazette about the evolution of the crisis and the challenges ahead.

You came to the Treasury Department in 2006. How has the view from your office changed since then with respect to the economy and our financial system?

When we came in July 2006, the economy was very strong and the financial markets were doing very well, and there was a great deal of confidence. Obviously now we’re in a different place. The economy has seen headwinds and the financial system is under a great deal of stress. So our views have changed quite a bit, but I think we’re all optimistic that once we get through this period, our country is positioned to continue to be very strong and see very good growth long-term.

I understand you were up all night putting together this bailout bill with Henry Paulson and others. What were the main things you wanted to accomplish as you sat together in that room?

First of all, the plan itself began germinating six-to-nine months ago, as a contingency plan. We hoped we wouldn’t need it. In the last few weeks, before we got the legislation and we were crafting the details, the key for us was to get enormous authority—meaning enormous power—to be able to tackle this problem. Hence the $700 billion. And second, broad discretion to use it in a variety of different ways. Because the one constant over the last 14 months is that the credit crisis has been always changing.

How did it feel when the House initially shot the proposal down?

It was disappointing, and a little bit frightening. Because we knew what we were facing, and we knew we had to have this authority. And candidly, if we ultimately didn’t get it, history would have showed that we at least tried to get it.

Right now a lot of people are worried about a potential collapse in credit default swaps, a market that’s grown more than 50-fold since 2000 to become worth somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 trillion—which is more than all the U.S. stock shares and mortgage securities combined. In that context, does this $700 billion you have to work with seem like a lot or a little?

It’s a lot when you’re going at the root of the problem. What you’re seeing in these related markets—whether it’s the commercial paper market, the CDS market, the municipal market—these are all symptoms of an underlying disease. The underlying disease is that there’s insufficient capital in our financial system, in part because of these toxic assets—people don’t know how much they’re worth, and it’s hard for financial institutions to raise more capital to offset the losses that are coming. So the $700 billion is a big number compared to what the system needs. So yes, there are these bigger markets that are affected by this, but we believe if we can solve the root of the problem, then these other markets will become healthy as a result of that.

Where is the root of the problem?

The root of the problem is fundamentally in the mortgage market. You know, it’s a $12 trillion market. Banks hold a lot of mortgages on their books, both in the form of individual loans as well as packaged up into securities—like mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations. And it’s these assets that the banks really don’t know how much they’re worth, because the mortgage market is still correcting, and home prices are still falling, and the housing market adjusts very slowly. All housing markets do. So banks are in a place right now where they’re having to protect their capital, not make loans, because they don’t know how big their losses are going to be. And big investors are scared because they don’t know which financial institutions are undercapitalized. So they’re pulling back from all of them. Because they’re afraid; it’s a crisis of confidence.

So all that pullback from financial institutions is creating a liquidity problem for all institutions. That’s why our plan is focused on mortgages and mortgage-related assets, and the financial institutions that hold a lot of them. Our belief is, if we can solve that problem, by taking these illiquid assets off the books and helping the banks recapitalize, that will help cure the disease, and then the symptoms will solve themselves.

Mortgage-backed securities have gotten a lot of the blame for setting off this crisis. In your view, how significant were capitalization rules that allowed brokerage houses to amplify their exposure to those kinds of instruments through these huge leverage ratios that we read about?

I think it was a combination of regulatory challenges as well as poor mortgage-origination practices, which had a huge role to play in this. And let’s be honest, homeowners buying homes they couldn’t afford, and everyone speculating. Everyone was at fault here. It couldn’t happen with any one of those things—all of those things had to happen together.

How do you see your responsibilities in this role? Presumably the government should always act to protect taxpayers, but how does that work when you’re tasked with using their money to buy assets that the private sector doesn’t want, and that, as you say, it considers “toxic”?

Our first priority is that this works to stabilize the system. And we want to do that in the least costly manner we can. So I agree with you: those are in tension. If it was taxpayer protection alone—well, let me say it another way. This is really important. The ultimate taxpayer protection is that we stabilize the financial system. If we don’t do this, and the financial system collapses, our taxpayers will end up paying much, much more than $700 billion to fix the system. So first of all, we have to fix the system. And then when we fix the system, let’s do it in a way that doesn’t waste taxpayer dollars.

When the House shot this bill down to begin with, some members asked, “Why stabilize the financial system? These guys are fat cats. Why is this our problem?”

This is about stabilizing everybody’s financial system. Every American relies on the financial system to either get a home loan, a credit card, auto loan, student loan. It’s how the hardware store down the street gets a bank line to fund its inventory, or to make payroll. It’s about big companies, industrial companies, how they fund themselves, or expand and open up new plants. This was every bit about every American and our economy, and what would happen to our economy if we didn’t take action.

What’s the best-case scenario for this rescue attempt?

It’s going to take some time to set up and get going. I am confident that we will get this going in an expeditious manner, but also in a high-quality manner. We’re not going to jump in all at once. We’re going to try some things, we’re going to see how they’re working, we’re going to adjust and adapt. I think there’s a good chance that we’re going to pull through this. It’s going to be rocky—for months—but the financial markets will begin to heal themselves and our economy will begin growing again.

Do you expect to be coordinating with foreign actors as you try to figure out how to spend this money?

We’re in active dialogue with governments around the world—leaders of central banks and finance ministries. This is our ordinary course. So we’re already sharing our ideas and hearing their ideas. Everyone’s system is a little different, so the right approach in the United States may not be optimal for another country, and vice versa, but to the extent that our friends take similar measures, or measures that complement us, we think we’ll all be more effective. So we’re trying to coordinate as much as possible, but we’re also not slowing down.

Any lessons we can take out about how to avoid falling into this trap again?

You know, we’re all very good at fixing the last problem. I don’t expect in the near-future we’re going to have mortgages that are underwritten with no documentation and no money down, as an example. And I’m certain that the next Congress and the next administration are going to take a fresh look at regulatory standards in the U.S. Even at the Treasury Department, we’ve published our own blueprint for how we think the regulatory system should look in the future. Our regulatory system has come up over the course of 80 years, and is a patchwork quilt that isn’t really suited for the complex financial system we have today.

But there are no guarantees. I think what’s great about our economy and our financial system is how innovative it is, and this time is an example of when it got a little over its skis. But we don’t want to quash innovation. That innovation is very important for us to continue to grow and lead.

How does this job stack up against your previous career in rocket science?

They’re both intellectually stimulating. I love the research I was doing, because we were trying to solve things that had never been solved before. And that’s the same thing in policy, what we’re trying to do in the credit crisis. There have been crises in the past, but each is unique, and so we’re trying to tackle things that have never been done before. So they’re both unbelievably stimulating, intellectually. But the pressure and the stakes here are just infinitely higher.