In the summer of 1999, Rachel Eisenberg Braun C’80 G’80, a self-described “mathy person who has always appreciated a good piece of graph paper,” walked into an Amherst, Massachusetts, paper shop.

The back room was overflowing with vintage sheets. There were new ones, too, but those didn’t entice Braun the same way. She began buying a few packs of paper at a time, returning to that store and visiting others, and now she holds the world record for largest graph paper collection: a thousand unique pages.

Braun spoke with the Gazette about her massive collection and the artists it’s attracted, and also discussed her passion for Judaic embroidery—which involves graph paper, too. (This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited.)

What inspired you to start collecting graph paper?

Graph paper has two main attributes of beauty. One is the paper itself. Some of the old manufacturers used high rag content paper—50 to 100 percent rag—that drapes beautifully in the hand. Other papers come in lovely, glistening vellum. Remember, highly paid engineers, architects and Disney designers, among others, used graph paper professionally before computer printers spit out graphs on really ordinary paper. Just as professionals today prize a good keyboard or an elegant pen, these professionals used high-quality papers as part of their professional material culture.

Another beautiful aspect of graph paper is the design of the grid and the representation of patterns in the world that are implicit in those grids. I have graph papers in a variety of grids: the usual squares, of course, plus semilogarithmic, logarithmic, isometric, hyperbolic, normal probability plot, polar coordinate, Smith Chart, triangular, knitting and quilting grids, Skew-T (that’s meteorological paper) and more. Each of these grids describe a particular reality that creates order in a graph.

Where have you looked to find so much graph paper?

I teach math, so there’s lots of cool papers in the drawers at work. I have also found beautiful graph paper in paper stores, college bookstores and artist supply shops, and I look for ephemera on Etsy and eBay. Friends whose parents are engineers have given me papers, and colleagues of friends and relatives—when they hear about my interest—find old papers to share.

What are some of your favorite papers?

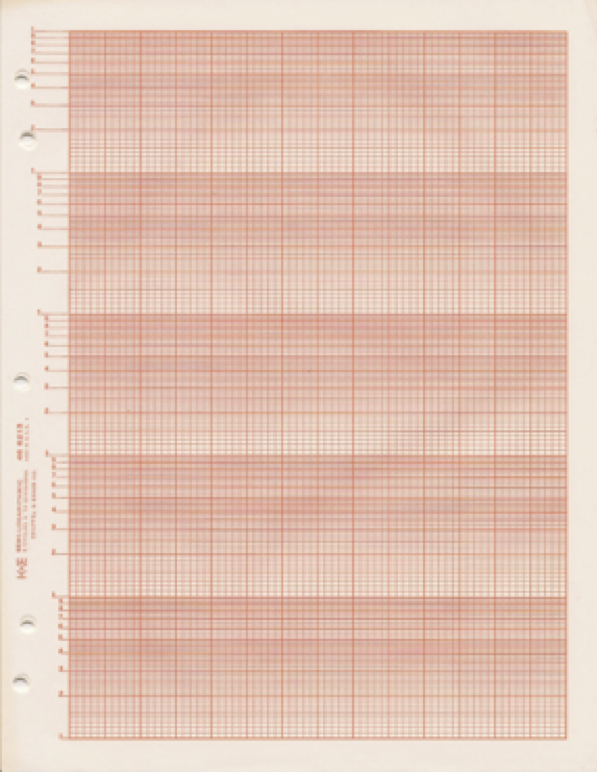

This semilogarithmic grid paper is Keuffel & Esser brand, code 46 6213. I have 107 distinct semilog papers with different manufacturers and code numbers.

This semilogarithmic grid paper is Keuffel & Esser brand, code 46 6213. I have 107 distinct semilog papers with different manufacturers and code numbers.

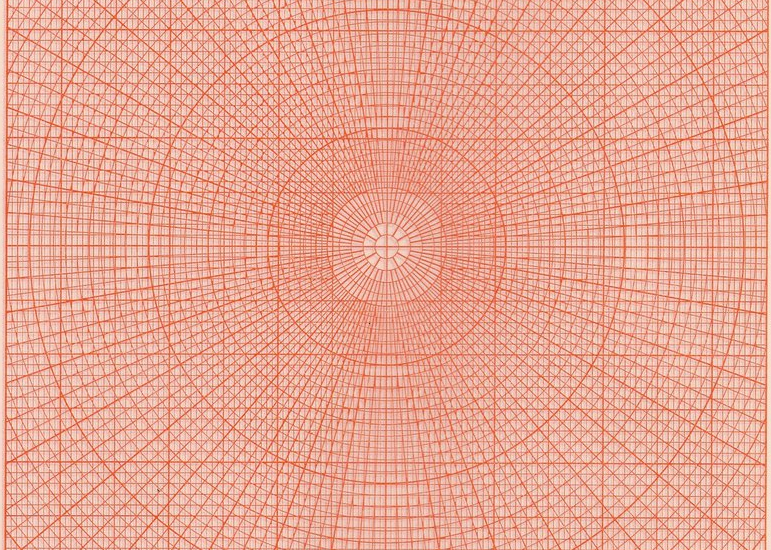

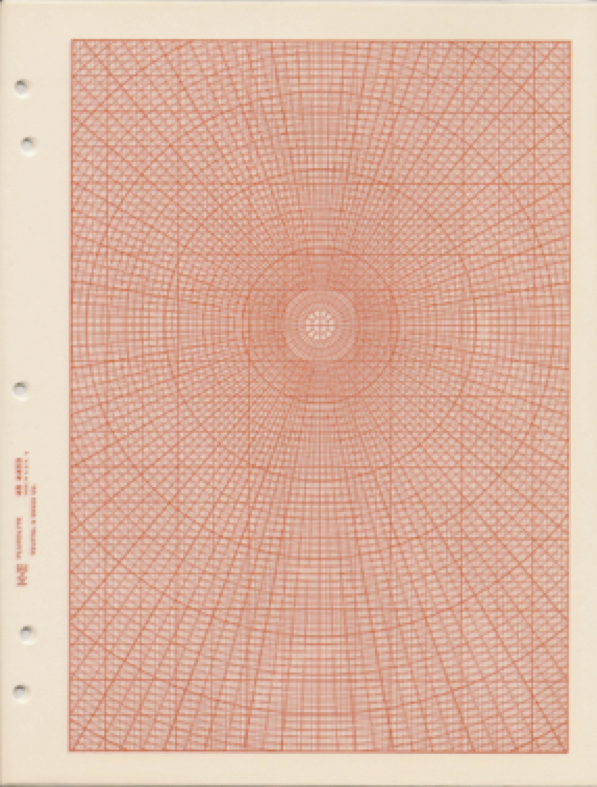

This paper is called Fluxolite. It’s a polar grid superimposed on a rectangular one, used by lighting engineers to solve illumination problems.

This paper is called Fluxolite. It’s a polar grid superimposed on a rectangular one, used by lighting engineers to solve illumination problems.

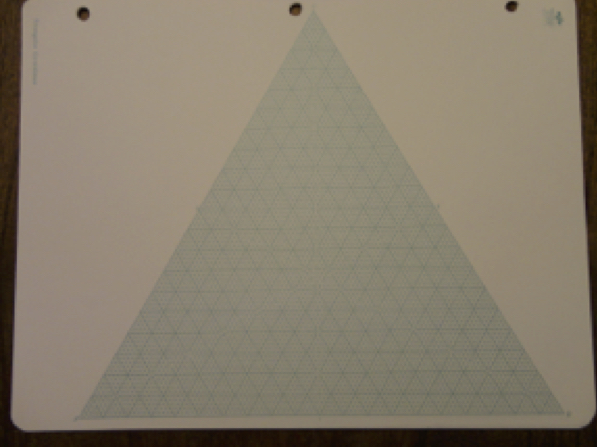

Triangular grid paper is used to graph three variables whose sum is a constant. The resulting graphs are called “ternary plots” and are useful in physical chemistry and other physical sciences.

Triangular grid paper is used to graph three variables whose sum is a constant. The resulting graphs are called “ternary plots” and are useful in physical chemistry and other physical sciences.

What are most people missing about graph paper—what’s something you’d love for them to pay more attention to or appreciate more?

If it’s a good quality vintage paper, the sheen and drape. If they are interested in history or the history of technology, I love papers that have a brand name printed on them, such as Disney, NYC Parks and Planning, Bell Labs, General Electric, NASA Ames Research Center, USDA Forest Service, John Deere, and Tennessee Valley Authority. All these connect graph paper to economic and technological progress. They represent professionals in a diversity of fields using this medium to critically organize the information they need to be effective.

Do you see graph paper as a form of art?

No, I see it as a form of reality. It shows us what surfaces look like in other, nonrectangular realities. But I have been surprised at how well-received graph paper is among artists. I opened up an Etsy shop in 2014 called TheGiddyGrid where I sell my excess graph paper. I imagined that the target clientele was fellow math geeks who would purchase a pack and gaze lovingly at the papers. It turns out I have communicated with scrapbookers, calligraphers, painters and collage artists who find the medium stimulating.

Tell me about your Judaic embroidery. How did you get into it? I’d imagine all that graph paper comes in handy when you’re planning designs.

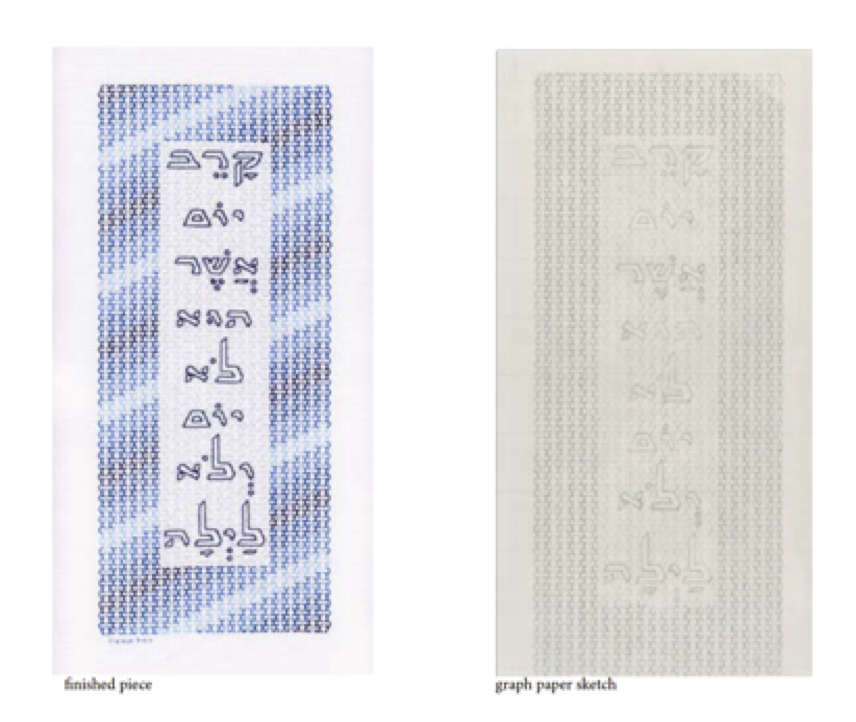

I was embroidering a cloth Torah binder to mark my older daughter’s bat mitzvah in 1997. I used a graph paper pattern I had purchased from a Judaic embroidery shop, but I was completely inexperienced, so I used the wrong needles. I pricked my finger and bled all over the pattern, a skyline of Jerusalem. I leaped up to wash out the stain—to no avail. Then I realized that if I just did a bit of my own sketching on the graph paper pattern, I could move the Jerusalem buildings around and cover the stain. Once I tried that, I thought, ‘This is fun! I don’t need someone else’s pattern!’ And so began my embroidery design career.

What are some favorite designs from your recent book, Embroidery and Sacred Text?

“God Counts the Stars” (2015) is based on a favorite text from Psalms 147: “God counts the stars, giving each a name, with grandeur and power, wisdom beyond measure.” Each star in my design has its own needlework pattern, the embroiderer’s version of “giving each a name.” So the art interprets the text, but it also mimics the text and exposes the text.

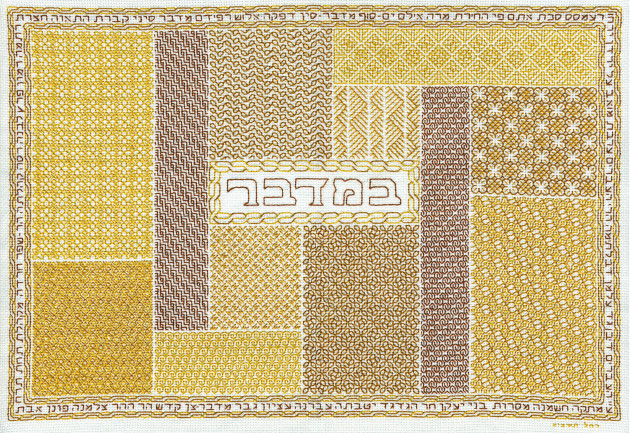

Another favorite is “Bamidbar: In the Wilderness” (2011). This piece was selected for a 2014 juried exhibit of the American Mathematical Society. It’s another favorite text, especially for us boring statisticians. The book of numbers, called Bamidbar in Hebrew, recounts the stops of the wandering Israelites from Egypt to the Promised Land. This design was meant to provoke the feeling of desert wanderings. Within each pattern block, there are interesting mathematical symmetries: rotations, translations and reflections, each with its own mathematical code.

Embroidery scans by Philip Brookman

—Molly Petrilla C’06