Armageddon, bomb shelters, and rock ‘n’ roll.

By Rick Levy

When I was 13, I played my first Martin guitar. It was a classic folk model with nylon strings, and I would accompany my sister, Judi, who was three years older. We would harmonize on “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “Stewball,” “Tom Dooley,” and other folk favorites. It was 1962. We were very clean, and most importantly, we were soft. We could even perform a few ditties at our parents’ dinner parties. I’d wear a black roll-neck sweater.

But something happened that autumn, and afterward my life would never be the same.

In mid-October, a U-2 spy plane revealed that the Soviet Union had deployed ballistic missiles in Cuba. Millions of Americans were suddenly struck with the fear that they were going to be incinerated by the Red Menace. The Levy household was by no means immune, yet for my enterprising father the missile crisis also represented a business opportunity of potentially historic dimensions. Certain that middle-class Americans would want protection from impending doom, he and a friend decided to go into the bomb shelter business.

Mort Levy W’39, who’d played football under famed coach George Munger Ed’33 back in the heyday of Franklin Field, was already a successful businessman in Allentown, Pennsylvania. My dad built up the clothing business his father had started, and at one time had 500 employees in his clothing factories. But his friend may have been the savvier of the pair, in at least one respect. At the outset the partners made a bet of some kind, stipulating that the loser would have to have the prototype built in his own home. And my father lost.

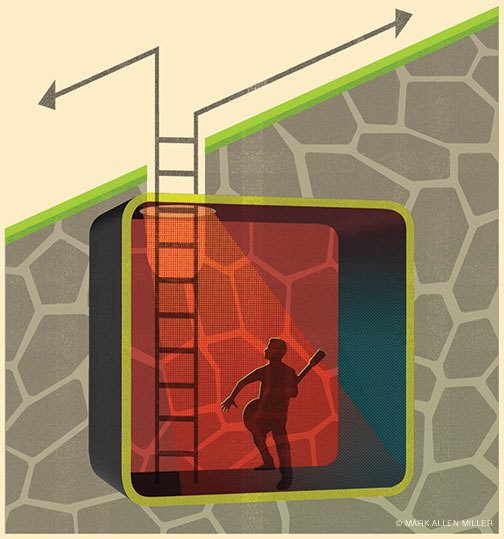

So it came to pass that early in 1963, a bulldozer, backhoe, and cement trucks rolled up in front of our home in Allentown’s well-to-do West End neighborhood. Over the next several weeks, a cavity was excavated beneath our basement, and fashioned into a concrete tomb. Its walls, which were three feet thick, were only the beginning of the surreal scene. At the back end of the basement, several steps led down to a pair of steel stable doors fitted with a sliding speakeasy-style peephole—through which, presumably, we would be able to take the measure of whatever half-eaten survivors might try to join us in our post-apocalyptic refuge. The interior, which was about 12 feet long and eight wide, featured four spartan cots folded against the bare concrete walls. These would release on chains. There were also some shelves stocked with what my father judged to be a two-week supply of food, water, and medicine. Whether two weeks would be long enough to wait out nuclear Armageddon was, as far as I knew, an unexamined proposition. The fact that the doors lacked any kind of protective seal cast the utility of the whole thing into question.

But there was no denying the imagination that had gone into any number of details. The best part was the little chemical toilet hidden behind a shower curtain. The thought of doing our business behind this flimsy barrier was almost too much to bear. My father, in this regard, was not a quiet man. But the question begged by that prospect—how were we to breathe?—had a ready answer. A crank-handled intake fan was supposed to bring fresh air into the shelter, and the designers assured us that a filter would keep out radiation and contaminants.

If this wasn’t insane enough, for months my dad would conduct periodic drills, using his stopwatch to time how long it took all of us to get down into the shelter. We’d check the Geiger counter, food supplies, and the dreaded chemical toilet. My sister and I finally announced that we’d rather die than stay down there for two weeks.

Of course it never came to that, but many years later, when Judi and I were preparing to sell the house after my father died, we pried open a secret panel that had been bolted shut for 45 years. Inside was an honest-to-God handgun. Who knows whether it was for intruders, or for us, had the world indeed ended.

If I hadn’t quite been able to put my finger on what I’d started feeling as a kid hitting his teens just as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were landing on the FM dial, the installation of a concrete bunker beneath our home put a point on it: I was already sheltered enough. So while my dad set about looking for customers, I convinced my mom to drive me to the “bad section” of town for a weekly guitar lesson with a chain-smoking genius who stood as an emblem of everything my family wasn’t.

Watts Clark had a shaved head, a Camel cigarette posed perpetually between his lips, and dressed exclusively in black. His neighborhood wasn’t actually bad, but its blue-collar row homes were a world away from the groomed lawns I knew, and I relished travelling beyond the bounds of my comfort zone.

And the journey was more than geographical. In the majestic gloom of his dark, vaguely ominous apartment, Watts delicately conjured angels from the strings of his D’Angelico guitar. How this man had ended up in Allentown, after a life crisscrossing the country in big bands and jazz combos, was a mystery to me. Years later I learned that his exotic past existed mostly in my imagination; he’d been born 10 miles down the road in Bethlehem, and had mostly played locally. But as a teenage boy encountering the musician’s life for the first time, I saw him as I wanted to see him—and as he in fact was: my guru. The technical and theoretical skills he imparted were foundational. The melodic and harmonic concepts he taught me—modal scales and chords I didn’t even have names for—would become integral to my style of rock and soul playing. It took me years to process the rhythmic knowledge he imparted, and to this day I continue to unlock new aural dimensions he first pointed me toward. But beyond that, he embodied a mode of existence that crystallized what I yearned for—freedom from regimentation, expansiveness of expression, creativity without end—and showed me that I could find it in a life devoted to music.

Yet I wonder, would those afternoons with Watts have affected me so profoundly if our basement had remained a simple realm of particle-board and file cabinets? Years later, my friend Peggy Salvatore reflected on what growing up in the shadow of the Bomb did to certain of us.

“We lived in the face of death,” she mused. “We had a sense that life was senseless, that we wouldn’t live a full life and we didn’t have control of a future we might not even have. Peace, love, and rock ‘n’ roll. Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll … it all ended in rock ‘n’ roll.”

My dad’s business venture failed miserably. Not one other shelter was built. Ours became a cold, dank refuge for bugs, spiders, and all sorts of mold and other creatures. The only saving grace was that during my college years, I’d bring friends home and we’d go down to the bomb shelter to get high. (The filtered intake fan worked!) Occasionally I thought about sneaking girls down there, but that was just too creepy. So I contented myself with a hobby that has brought me fulfillment ever since, through what’s now more than a half-century of playing music for a living. Playing guitars that reverberated massively against the concrete walls was, to me, a much better use of that room than waiting to see if any life was left after the fallout. It was the beginning of a lifetime of joyful noise.

Rick Levy C’71 (ricklevy.com) is the author of High in the Mid-’60s: How to Have a Fabulous Life in Music Without Being Famous, from which this essay is adapted.